(Press-News.org) Cutting back on animal protein in our diets can save on resources and greenhouse gas emissions. But convincing meat-loving consumers to switch up their menu is a challenge. Looking at this problem from a mechanical engineering angle, Stanford engineers are pioneering a new approach to food texture testing that could pave the way for faux filets that fool even committed carnivores.

In a new paper in Science of Food, the team demonstrated that a combination of mechanical testing and machine learning can describe food texture with striking similarity to human taste testers. Such a method could speed up the development of new and better plant-based meats. The team also found that some plant-based products are already nailing the texture of the meats they’re mimicking.

“We were surprised to find that today’s plant-based products can reproduce the whole texture spectrum of animal meats,” said Ellen Kuhl, professor of mechanical engineering and senior author of the study. Meat substitutes have come a long way from when tofu was the only option, she added.

Industrial animal agriculture contributes to climate change, pollution, habitat loss, and antibiotic resistance. That burden on the planet can be eased by swapping animal proteins for plant proteins in diets. One study estimated that plant-based meats, on average, have half the environmental impact as animal meat. But many meat eaters are reluctant to change; only about a third of Americans in one survey indicated they were “very likely” or “extremely likely” to buy plant-based alternatives.

“People love meat,” said Skyler St. Pierre, a PhD student in mechanical engineering and lead author of the paper. “If we want to convince the hardcore meat eaters that alternatives are worth trying, the closer we can mimic animal meat with plant-based products, the more likely people might be open to trying something new.”

To successfully mimic animal meat, food scientists analyze the texture of plant-based meat products. Unfortunately, traditional food testing methods are not standardized and the results are rarely made available to science and to the public, said St. Pierre. This makes it harder for scientists to collaborate and create new recipes for alternatives.

New food texture tests

The research grew out of a class project by St. Pierre. Looking for affordable materials to use in mechanical tests, he turned to hot dogs and tofu. Over the summer of 2023, undergraduate researchers joined in to test the foods and learn how engineers depict material responses to stress, loading, and stretching.

Realizing how this work could aid the development of plant-based meats, the Stanford team debuted a three-dimensional food test. They put eight products to the test: animal and plant-based hot dog, animal and plant-based sausage, animal and plant-based turkey, and extra firm and firm tofu. They mounted bits of meat into a machine that pulled, pushed, and sheared on the samples. “These three loading modes represent what you do when you chew,” said Kuhl, who is also the Catherine Holman Johnson Director of Stanford Bio-X and the Walter B. Reinhold Professor in the School of Engineering.

Then, they used machine learning to process the data from these tests: They designed a new type of neural network that takes the raw data from the tests and produces equations that explain the properties of the meats.

To see if these equations can explain the perception of texture, the team carried out a test survey. The testers – who first completed surveys on their openness to new foods and their attachment to meat – ate samples of the eight products and rated them on 5-point scale for 12 categories: soft, hard, brittle, chewy, gummy, viscous, springy, sticky, fibrous, fatty, moist, and meat-like.

Impressive hot dogs and sausages

In the mechanical testing, the plant-based hot dog and sausage behaved very similarly in the pulling, pushing, and shear tests to their animal counterparts, and showed similar stiffnesses. Meanwhile, the plant-based turkey was twice as stiff as animal turkey, and the tofu was much softer than the meat products. Strikingly, the human testers also ranked the stiffness of the hot dogs and sausages very similarly to the mechanical tests. “What’s really cool is that the ranking of the people was almost identical to the ranking of the machine,” said Kuhl. “That’s great because now we can use the machine to have a quantitative, very reproducible test.”

The findings suggest that new, data-driven methods hold promise for speeding up the process of developing tasty plant-based products. “Instead of using a trial-and-error approach to improve the texture of plant-based meat, we could envision using generative artificial intelligence to scientifically generate recipes for plant-based meat products with precisely desired properties,” the authors wrote in the paper.

But artificial intelligence recipe development, like other AIs, needs lots of data. That’s why the team is sharing their dataonline, making it open for other researchers to view and add to. “Historically, some researchers, and especially companies, don’t share their data and that’s a really big barrier to innovation,” said St. Pierre. Without sharing information and working together, he added, “how are we going to come up with a steak mimic together?”

The team is continuing to test foods and build a public database. This summer, St. Pierre oversaw undergraduates testing veggie and meat deli slices. The researchers also plan to test engineered fungi developed by Vayu Hill-Maini, who recently joined Stanford as an assistant professor of bioengineering. “If anybody has an artificial or a plant-based meat they want to test,” said Kuhl, “we’re so happy to test it to see how it stacks up.”

For more information

Additional Stanford co-authors of the paper include Marc Levenston, associate professor of mechanical engineering; postdoctoral researcher Kevin Linka; graduate students Ethan C. Darwin, Divya Adil, and Valerie A. Perez Medina; visiting researcher María Parra Vallecillo; and undergraduate researchers Magaly C. Aviles, Archer Date, Reese A. Dunne, and Yanav Lall.

Kuhl is also a professor, by courtesy, of bioengineering in the schools of Engineering and Medicine, and a member of the Cardiovascular Institute, the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance, the Institute for Computational and Mathematical Engineering, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Levenston is also a member of Bio-X, the Cardiovascular Institute, the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance and the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute.

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Emmy Noether Programme, and the European Research Council.

END

Can AI improve plant-based meats?

2024-11-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How microbes create the most toxic form of mercury

2024-11-15

Mercury is extraordinarily toxic, but it becomes especially dangerous when transformed into methylmercury – a form so harmful that just a few billionths of a gram can cause severe and lasting neurological damage to a developing fetus. Unfortunately, methylmercury often makes its way into our bodies through seafood – but once it’s in our food and the environment, there’s no easy way to get rid of it.

Now, leveraging high-energy X-rays at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, ...

‘Walk this Way’: FSU researchers’ model explains how ants create trails to multiple food sources

2024-11-15

It’s a common sight — ants marching in an orderly line over and around obstacles from their nest to a food source, guided by scent trails left by scouts marking the find. But what happens when those scouts find a comestible motherlode?

A team of Florida State University researchers led by Assistant Professor of Mathematics Bhargav Karamched has discovered that in a foraging ant’s search for food, it will leave pheromone trails connecting its colony to multiple food sources when they’re available, ...

A new CNIC study describes a mechanism whereby cells respond to mechanical signals from their surroundings

2024-11-15

To the casual eye, a memory foam mattress would appear to have no relationship to the behavior of cells and tissues. But an innovative study carried out at the Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) in Madrid shows that viscoelasticity—the capacity of a material to be compressed and then recover its original form, like memory foam—is a little-explored property of biological tissues that is essential for correct cell function.

Study leader Dr. Jorge Alegre-Cebollada, who heads the Molecular Mechanics of the Cardiovascular System laboratory at the CNIC, explained that proper cell function requires ...

Study uncovers earliest evidence of humans using fire to shape the landscape of Tasmania

2024-11-15

Some of the first human beings to arrive in Tasmania, over 41,000 years ago, used fire to shape and manage the landscape, about 2,000 years earlier than previously thought.

A team of researchers from the UK and Australia analysed charcoal and pollen contained in ancient mud to determine how Aboriginal Tasmanians shaped their surroundings. This is the earliest record of humans using fire to shape the Tasmanian environment.

Early human migrations from Africa to the southern part of the globe were well underway during the early part of the last ice age – humans reached northern ...

Researchers uncover Achilles heel of antibiotic-resistant bacteria

2024-11-15

Recent estimates indicate that deadly antibiotic-resistant infections will rapidly escalate over the next quarter century. More than 1 million people died from drug-resistant infections each year from 1990 to 2021, a recent study reported, with new projections surging to nearly 2 million deaths each year by 2050.

In an effort to counteract this public health crisis, scientists are looking for new solutions inside the intricate mechanics of bacterial infection. A study led by researchers at the University of California San Diego has discovered a vulnerability within strains of bacteria that are antibiotic resistant.

Working with labs at Arizona State University and the Universitat ...

Scientists uncover earliest evidence of fire use to manage Tasmanian landscape

2024-11-15

Some of the first humans to arrive in Tasmania, over 41,000 years ago, used fire to shape and manage the landscape, a new study from The Australian National University (ANU) and the University of Cambridge has found.

It is thought to be the earliest and most detailed record of humans using fire in the Tasmanian environment.

According to the researchers, early inhabitants of Tasmania were managing forests and grasslands by burning them to create open spaces, possibly for food procurement and cultural activities.

The team analysed traces of charcoal and pollen contained in ancient mud that showed how Indigenous Tasmanians (Palawa) ...

Interpreting population mean treatment effects in the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

2024-11-15

About The Study: Inferences about clinical impacts based on population-level mean treatment effects may be misleading, since even small between-group differences may reflect clinically important treatment benefits for individual patients. Results of this study suggest that clinical trials should explicitly describe the distributions of Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire change at the patient level within treatment groups to support the clinical interpretation of their results.

Corresponding ...

Targeting carbohydrate metabolism in colorectal cancer: Synergy of therapies

2024-11-15

“This commentary will discuss what is known about such combinatorial treatments, including potential mechanisms and future protocols.”

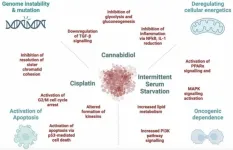

BUFFALO, NY- November 15, 2024 – A new review was published in Volume 11 of Oncoscience on November 12, 2024, entitled, “Targeting carbohydrate metabolism in colorectal cancer - synergy between DNA-damaging agents, cannabinoids, and intermittent serum starvation.”

As highlighted by the authors in the abstract of this review, chemotherapy is a common treatment for many cancers. However, it is often ineffective for long-term patient survival and ...

Stress makes mice’s memories less specific

2024-11-15

Stress is a double-edged sword when it comes to memory: stressful or otherwise emotional events are usually more memorable, but stress can also make it harder for us to retrieve memories. In PTSD and generalized anxiety disorder, overgeneralizing aversive memories results in an inability to discriminate between dangerous and safe stimuli. However, until now, it wasn’t clear whether stress played a role in memory generalization.

Now, neuroscientists report November 15 in the Cell Press journal Cell that acute stress prevents mice from forming specific memories. Instead, the stressed mice formed generalized memories, which are ...

Research finds no significant negative impact of repealing a Depression-era law allowing companies to pay workers with disabilities below minimum wage

2024-11-15

PHILADELPHIA—Debate continues to swirl nationally on the fate of a practice born of an 86-year-old federal statute allowing companies to pay workers with disabilities subminimum wages: anything below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, but for some roles as little as 25-cents-per-hour. Those in favor of repealing this statute highlight assumptions about reduced productivity along with the unfairness of this wage level—often used elsewhere to pay, for example, food service workers who typically make additional wages in tips. Those against repeal have voiced concerns that, without subminimum ...