(Press-News.org) Researchers from the Champalimaud Foundation shed light on the puzzling relationship between dopamine and rest tremor in Parkinson’s disease, finding that preserved dopamine in certain brain regions may actually contribute to tremor symptoms, challenging common beliefs.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive neurological disorder known for its characteristic motor symptoms: tremor, rigidity, and slowness of movement. Among these, rest tremor—a shaking that occurs when muscles are relaxed—is one of the most recognisable yet least understood.

A new study from the Champalimaud Foundation published in npj Parkinson’s Disease, led by the Neural Circuits Dysfunction Lab in collaboration with the Neuropsychiatry and Nuclear Medicine Labs, offers fresh insights into the complex relationship between rest tremor and dopamine, a chemical messenger that plays a key role in coordinating movement.

The Dopamine Paradox

Dopamine loss in brain regions like the putamen, associated with movement regulation, is a well-established hallmark of PD. However, while some patients experience significant tremor relief with dopamine replacement therapies like L-DOPA, others see little to no improvement, or even a worsening of symptoms. “Tremor is a common and often debilitating symptom for PD patients, but it has always been a bit of a puzzle”, says Marcelo Mendonça, one of the study’s lead authors. “We know dopamine is involved, but the way it affects tremor isn’t as direct as with other motor symptoms”.

Conventional wisdom suggests that less dopamine should correspond to more severe symptoms. However, the researchers found the opposite to be true when it comes to rest tremor. “Paradoxically, we discovered that patients who exhibit tremor have more dopamine preserved in the caudate nucleus, a part of the brain important for movement planning and cognition”, explains Mendonça. “This challenges our traditional understanding of how dopamine loss relates to PD symptoms”.

An Overlooked Player in Tremor?

Using data from patients at the Champalimaud Clinical Centre and public databases, the researchers analysed information from over 500 patients. This diverse dataset included clinical assessments, DaT scans to visualise dopaminergic neurons, and wearable motion sensors that precisely measure tremor severity.

“Wearable motion sensors gave us a clearer, more objective measurement of tremor", says co-first author Pedro Ferreira. “On the surface, patients with and without dopamine loss in the caudate seem similar. However, sensors reveal subtle differences in tremor oscillations that traditional clinical rating scales might miss, and they’re relatively easy to use, allowing us to reliably connect symptoms with what’s happening in the brain”.

“By combining imaging data with measurements from these sensors, we observed a clear link between dopamine function in the caudate nucleus and global severity of resting tremor”, continues Ferreira. “Our analysis suggests that the more dopamine activity preserved in the caudate, the stronger the tremor”.

Senior author Joaquim Alves da Silva, head of the Neural Circuits Dysfunction Lab, picks up the story: “This is the first large study to clearly show a link between better-preserved dopamine levels in the caudate and the presence of rest tremor. Although patients with rest tremor have lost dopamine-releasing nerve endings in the caudate, they actually have more of these nerve endings preserved compared to patients without tremor”.

One of the most intriguing findings of the study was that the more dopamine was preserved in the caudate on one side of the brain (each hemisphere has its own caudate), the more tremor there was on the same side of the body. “This was quite unexpected”, says Alves da Silva. “Usually, each side of the brain controls movement on the opposite side of the body”. Their computational model found that this “same-side” effect could arise spuriously from two factors: the generally higher dopamine in both caudates in tremor patients and the uneven way PD affects each side of the brain.

Challenging Conventional Classifications

This study builds on earlier work by the same team, published last month in Neurobiology of Disease, which showed the value of treating rest tremor separately from other motor symptoms—a departure from traditional approaches that have lumped these symptoms together. Their prior research revealed that rest tremor varies with the type of PD progression: tremor, particularly when resistant to treatment, is more common in patients presenting a “brain-first” PD, while those without tremor present a symptom pattern more aligned with a “gut-first” PD, where the disease process starts in the gut and spreads to the brain.

This new study extends that line of inquiry, showing that the severity of rest tremor may be linked to specific brain circuits. “Dopamine loss in PD is not uniform—different patients may lose dopamine in distinct circuits”, notes Alves da Silva. “By focusing on rest tremor in isolation, we are in a better position to pinpoint the specific neural pathways involved. For instance, could tremor result from an imbalance in dopamine between the caudate and putamen? Identifying reliable biological correlates for individual symptoms is critical, as it paves the way for more targeted therapies aimed at relieving them”.

“Not all dopamine cells are alike”, adds Mendonça. “They have different genetic makeups, connections, and functions. This means that which cells a patient loses or keeps could affect their symptoms. For example, tremor might be tied to the loss or preservation of specific dopamine populations that connect to certain brain areas. This variation in cell type loss could further explain the wide range of symptoms among PD patients”.

Implications for Treatment and Future Research

The team is already looking ahead, says Alves da Silva. “It’s difficult to establish causality between dopamine preservation in the caudate and rest tremor in humans, which is why we’d like to test this in animal models, where we can manipulate specific cells and observe the effects on tremor. We’d also like to use advanced imaging techniques, like high-resolution dopamine PET scans and MRI, to identify key nodes in the dopamine system and link them to specific motor symptoms. This approach could help us better understand why PD symptoms differ from one patient to another”.

The research highlights the importance of looking beyond general classifications in PD and underscores the need for more nuanced approaches informed by underlying biology. “By identifying the specific neural circuits involved, we hope to clear the mist surrounding the heterogeneity of PD symptoms and contribute to more precise interventions that can improve the quality of life for those affected by this disease”, concludes Mendonça.

END

Parkinson’s Paradox: When more dopamine means more tremor

2024-11-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study identifies strategy for AI cost-efficiency in health care settings

2024-11-18

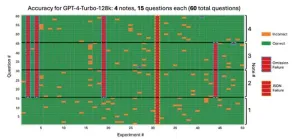

New York, NY [November 18, 2024]—A study by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai has identified strategies for using large language models (LLMs), a type of artificial intelligence (AI), in health systems while maintaining cost efficiency and performance.

The findings, published in the November 18 online issue of npj Digital Medicine [DOI: 10.1038/s41746-024-01315-1], provide insights into how health systems can leverage advanced AI tools to automate tasks efficiently, saving time and reducing operational costs while ensuring these models remain ...

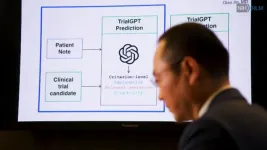

NIH-developed AI algorithm successfully matches potential volunteers to clinical trials release

2024-11-18

Researchers from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have developed an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm to help speed up the process of matching potential volunteers to relevant clinical research trials listed on ClinicalTrials.gov. A study published in Nature Communications found that the AI algorithm, called TrialGPT, could successfully identify relevant clinical trials for which a person is eligible and provide a summary that clearly explains how that person meets the criteria for study enrollment. The researchers ...

Greg Liu is in his element using chemistry to tackle the plastics problem

2024-11-18

As an undergraduate student at Zhejiang University in eastern China, Greg Liu went with some of his classmates on a university-sponsored trip to tour a host of chemical industries within the area.

The tour gave students pursuing degrees in chemical engineering an opportunity to learn more about the manufacturing and production processes of chemicals within China at the time. Liu realized that day exactly what he wanted to do for a career – find ways to alleviate or stop the industry from polluting the environment.

“I realized that this was not going to be the sustainable way of our future. Pollution ...

Cocoa or green tea could protect you from the negative effects of fatty foods during mental stress - study

2024-11-18

University of Birmingham News Release

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL Monday 18th November 2024 8.00am UK/ 3.00am EST

Cocoa or green tea could protect you from the negative effects of fatty foods during mental stress - study

New research has found that a flavanol-rich cocoa drink can protect the body’s vasculature against stress even after eating high-fat food.

Food choices made during periods of stress can influence the effect of stress on cardiovascular health. For example, recent research from the University of Birmingham found that high-fat foods can negatively affect vascular function and oxygen delivery to the brain, meanwhile flavanol compounds found in abundance in cocoa ...

A new model to explore the epidermal renewal

2024-11-18

The mechanisms underlying skin renewal are still poorly understood. Interleukin-38 (IL-38), a protein involved in regulating inflammatory responses, could be a game changer. A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has observed it for the first time in the form of condensates in keratinocytes, the cells of the epidermis. The presence of IL-38 in these aggregates is enhanced close to the skin’s surface exposed to atmospheric oxygen. This process could be linked to the initiation of programmed ...

Study reveals significant global disparities in cancer care across different countries

2024-11-18

A recent analysis reveals striking disparities in the cost and availability of cancer drugs across different regions of the globe, with significant gaps between high- and low-income countries. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

The analysis, which drew on relevant published studies and reviews related to cancer and the availability of cancer treatments, predicts that there will be an estimated 28.4 million new cancer cases worldwide in 2040 alone. In the coming years, cancer incidence is expected to increase most significantly in low-income countries. Cancer mortality ...

Proactively screening diabetics for heart disease does not improve long-term mortality rates or reduce future cardiac events, new study finds

2024-11-18

While coronary heart disease and diabetes are often seen in the same patients, a diagnosis of diabetes does not necessarily mean that patients also have coronary heart disease, according to a new study from researchers at Intermountain Health in Salt Lake City.

The Intermountain study found that proactively screening patients with diabetes 1 and 2 for coronary heart disease who have not shown symptoms of heart problems does not improve long-term mortality rates, nor does it lower the chance of them ...

New model can help understand coexistence in nature

2024-11-18

Different species of seabirds can coexist on small, isolated islands despite eating the same kind of fish. A researcher at Uppsala University has been involved in developing a mathematical model that can be used to better understand how this ecosystem works.

“Our model shows that coexistence occurs naturally when species differ in their ability to catch fish and to efficiently fly long distances to the area where they catch fish,” says Claus Rüffler, Associate Professor of Animal Ecology at Uppsala University.

Seabirds can breed in very large colonies, sometimes consisting of several hundred thousand pairs. Ecologists working ...

National Poll: Some parents need support managing children's anger

2024-11-18

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Many parents are all too familiar with angry outbursts from their children, from sibling squabbles to protests over screen time limits.

But some parents may find it challenging to help their kids manage intense emotions. One in seven think their child gets angrier than peers of the same age and four in 10 say their child has experienced negative consequences when angry, a new national poll suggests.

Seven in 10 parents even think they sometimes set a bad example of handling anger themselves, according to the University of Michigan Health ...

Political shadows cast by the Antarctic curtain

2024-11-18

The scientific debate around the installation of a massive underwater curtain to protect Antarctic ice sheets from melting lacks its vital political perspective. A Kobe University research team argues that the serious questions around authority, sovereignty and security should be addressed proactively by the scientific community to avoid the protected seventh continent becoming the scene or object of international discord.

A January 2024 article in Nature put the spotlight on a bold idea originally proposed by Finnish researchers to save the West Antarctic ...