(Press-News.org) Diamond rain? Super-ionic water?

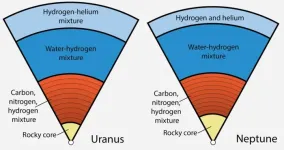

These are just two proposals that planetary scientists have come up with for what lies beneath the thick, bluish, hydrogen-and-helium atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune, our solar system's unique, but superficially bland, ice giants.

A planetary scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, now proposes an alternative theory — that the interiors of both these planets are layered, and that the two layers, like oil and water, don't mix. That configuration neatly explains the planets' unusual magnetic fields and implies that earlier theories of the interiors are unlikely to be true.

In a paper appearing this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Burkhard Militzer argues that a deep ocean of water lies just below the cloud layers and, below that, a highly compressed fluid of carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen. Computer simulations show that under the temperatures and pressures of the planets' interiors, a combination of water (H2O), methane (CH3) and ammonia (NH3) would naturally separate into two layers, primarily because hydrogen would be squeezed out of the methane and ammonia that comprise much of the deep interior.

These immiscible layers would explain why neither Uranus nor Neptune has a magnetic field like Earth's. That was one of the surprising discoveries about our solar system’s ice giants made by the Voyager 2 mission in the late 1980s.

"We now have, I would say, a good theory why Uranus and Neptune have really different fields, and it's very different from Earth, Jupiter and Saturn," said Militzer, a UC Berkeley professor of earth and planetary science. "We didn't know this before. It's like oil and water, except the oil goes below because hydrogen is lost."

If other star systems have similar compositions to ours, Militzer said, ice giants around those stars could well have similar internal structures. Planets about the size of Uranus and Neptune — so-called sub-Neptune planets — are among the most common exoplanets discovered to date.

Convection leads to magnetic fields

As a planet cools from its surface downward, cold and denser material sinks, while blobs of hotter fluid rise like boiling water — a process called convection. If the interior is electrically conducting, a thick layer of convecting material will generate a dipole magnetic field similar to that of a bar magnet. Earth's dipole field, created by its liquid outer iron core, produces a magnetic field that loops from the North Pole to the South Pole and is the reason compasses point toward the poles.

But Voyager 2 discovered that neither of the two ice giants has such a dipole field, only disorganized magnetic fields. This implies that there's no convective movement of material in a thick layer in the planets' deep interiors.

To explain these observations, two separate research groups proposed more than 20 years ago that the planets must have layers that can't mix, thus preventing large-scale convection and a global dipolar magnetic field. Convection in one of the layers could produce a disorganized magnetic field, however. But neither group could explain what these non-mixing layers were made of.

Ten years ago, Militzer tried repeatedly to solve the problem, using computer simulations of about 100 atoms with the proportions of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and hydrogen reflecting the known composition of elements in the early solar system. At the pressures and temperatures predicted for the planets' interiors — 3.4 million times Earth's atmospheric pressure and 4,750 Kelvin (8,000°F), respectively — he could not find a way for layers to form.

Last year, however, with the help of machine learning, he was able to run a computer model simulating the behavior of 540 atoms and, to his surprise, found that layers naturally form as the atoms are heated and compressed.

"One day, I looked at the model, and the water had separated from the carbon and nitrogen. What I couldn't do 10 years ago was now happening," he said. "I thought, 'Wow! Now I know why the layers form: One is water-rich and the other is carbon-rich, and in Uranus and Neptune, it's the carbon-rich system that is below. The heavy part stays in the bottom, and the lighter part stays on top and it cannot do any convecting.’"

"I couldn't discover this without having a large system of atoms, and the large system I couldn't simulate 10 years ago," he added.

The amount of hydrogen squeezed out increases with pressure and depth, forming a stably stratified carbon-nitrogen-hydrogen layer, almost like a plastic polymer, he said. While the upper, water-rich layer likely convects to produce the observed disorganized magnetic field, the deeper, stratified hydrocarbon-rich layer cannot.

When he modeled the gravity produced by a layered Uranus and Neptune, the gravity fields matched those measured by Voyager 2 nearly 40 years ago.

"If you ask my colleagues, 'What do you think explains the fields of Uranus and Neptune?' they may say, ‘Well, maybe it's this diamond rain, but maybe it's this water property which we call superionic,’" he said. "From my perspective, this is not plausible. But if we have this separation into two separate layers, that should explain it."

Militzer predicts that below Uranus' 3,000-mile-thick atmosphere lies a water-rich layer about 5,000 miles thick and below that a hydrocarbon-rich layer also about 5,000 miles thick. Its rocky core is about the size of the planet Mercury. Though Neptune is more massive than Uranus, it is smaller in diameter, with a thinner atmosphere, but similarly thick water-rich and hydrocarbon rich layers. Its rocky core is slightly larger than that of Uranus, approximately the size of Mars.

He hopes to work with colleagues who can test with laboratory experiments under extremely high temperatures and pressures whether layers form in fluids with the proportions of elements found in the protosolar system. A proposed NASA mission to Uranus could also provide confirmation, if the spacecraft has on board a Doppler imager to measure the planet's vibrations. A layered planet would vibrate at different frequencies than a convecting planet, Militzere said. His next project is to use his computational model to calculate how the planetary vibrations would differ.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (PHY-2020249) as part of the Center for Matter at Atomic Pressures.

END

A clue to what lies beneath the bland surfaces of Uranus and Neptune

Layers of material that, like oil and water, don't mix can explain planets' unusual magnetic fields

2024-11-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers uncover what makes large numbers of “squishy” grains start flowing

2024-11-25

Researchers Samuel Poincloux (currently at Aoyama Gakuin University) and Kazumasa A. Takeuchi of the University of Tokyo have clarified the conditions under which large numbers of “squishy” grains, which can change their shape in response to external forces, transition from acting like a solid to acting like a liquid. Similar transitions occur in many biological processes, including the development of an embryo: cells are “squishy” biological “grains” that form solid tissues and sometimes flow to form different organs. Thus, the experimental and theoretical framework elaborated here will help separate the ...

Scientists uncover new mechanism in bacterial DNA enzyme opening pathways for antibiotic development

2024-11-25

Researchers from Durham University, Jagiellonian University (Poland) and the John Innes Centre have achieved a breakthrough in understanding DNA gyrase, a vital bacterial enzyme and key antibiotic target.

This enzyme, present in bacteria but absent in humans, plays a crucial role in supercoiling DNA, a necessary process for bacterial survival.

Using high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy the researchers reveal unprecedented detail of gyrase’s action on DNA, potentially opening doors for new antibiotic therapies against resistant bacteria.

The research is published in Proceedings of the ...

New study reveals the explosive secret of the squirting cucumber

2024-11-25

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 20:00 GMT / 15:00 ET MONDAY 25 NOVEMBER 2024

New study reveals the explosive secret of the squirting cucumber

IMAGES AND VIDEO AVAILABLE – SEE NOTES SECTION BELOW

A team led by the University of Oxford has solved a mystery that has intrigued scientists for centuries: how does the squirting cucumber squirt? The findings, achieved through a combination of experiments, high-speed videography, image analysis, and advanced mathematical modelling, have been published today (25 November) in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The squirting cucumber (Ecballium elaterium, from the Greek ‘ekballein,’ meaning to throw out) is named for ...

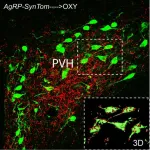

Vanderbilt authors find evidence that the hunger hormone leptin can direct neural development in a leptin receptor–independent manner

2024-11-25

Researchers from the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Basic Sciences have uncovered the first example of activity-dependent development of hypothalamic neural circuitry. Although previous research has shown that the hormone leptin acts directly on hunger neurons through leptin receptors to promote the development of neural circuitry, results that will be published in PNAS on Nov. 25 indicate that certain neurons that do not express leptin receptors are nonetheless sensitive to its activity.

The research, led by the lab of Richard Simerly, Louise B. McGavock Professor and professor of molecular physiology ...

To design better water filters, MIT engineers look to manta rays

2024-11-25

Filter feeders are everywhere in the animal world, from tiny crustaceans and certain types of coral and krill, to various molluscs, barnacles, and even massive basking sharks and baleen whales. Now, MIT engineers have found that one filter feeder has evolved to sift food in ways that could improve the design of industrial water filters.

In a paper appearing this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team characterizes the filter-feeding mechanism of the mobula ray — a family of ...

Self-assembling proteins can be used for higher performance, more sustainable skincare products

2024-11-25

If you have a meticulous skincare routine, you know that personal skincare products (PSCPs) are a big business. The PSCP industry will reach $74.12 billion USD by 2027, with an annual growth rate of 8.64%. With such competition, companies are always looking to engineer themselves an edge, producing products that perform better without the downsides of current offerings.

In a new study published in ACS Applied Polymer Materials from the lab of Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Jin Kim Montclare, researchers have created a novel protein-based gel as a potential ingredient in sustainable and high-performance PSCPs. This protein-based ...

Cannabis, maybe, for attention problems

2024-11-25

Cannabis — whether marijuana itself or various products containing cannabinoids and/or THC, the main psychoactive compound in weed – have been touted as panaceas for everything from anxiety and sleep problems to epilepsy and cancer pain.

Nursing researcher Jennie Ryan, PhD, at Thomas Jefferson University, studies the effects of cannabis on symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Current medical guidelines for ADHD include medications such as Adderall and cognitive behavioral therapy. ...

Building a better path to recovery for OUD

2024-11-25

A new study led by Thomas Jefferson University researchers highlights critical healthcare gaps that hinder long-term recovery for people living with opioid use disorders (OUD) in Philadelphia.

The researchers conducted 13 focus groups with 70 participants accessing various types of OUD treatment. Participants reported several challenges, such as lengthy and restrictive assessment processes, inadequate operating hours and lack of sufficient withdrawal management. Participants also reported broader socio-economic needs, such as housing and income support, as barriers to their recovery.

Meghan Reed, PhD, MPH, senior ...

How climate change threatens this iconic Florida bird

2024-11-25

ITHACA, N.Y. – Because of warmer winters, Florida scrub-jays are now nesting one week earlier than they did in 1981. But these early birds are not always getting the worm.

A new analysis of data from a long-term study, published in Ornithological Advances, finds that warmer winters driven by climate change reduced the number of offspring raised annually by the federally threatened Florida scrub-jay by 25% since 1981.

Warmer temperatures, the scientists hypothesize, make jay nests susceptible to predation by snakes for a longer period of the Florida ...

Study reveals new factor involved in controlling calorie expenditure

2024-11-25

An international team of researchers has discovered a new component of the peripheral nervous system that acts by increasing energy metabolism in the body. The finding paves the way for the development of simpler and cheaper drugs to control obesity and weight gain, regardless of the amount of food ingested.

In an article published in the journal Nature, researchers from the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom and the Obesity and Comorbidities Research Center (OCRC) – funded by FAPESP and based at the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in Brazil – describe where and how this component ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Green hydrogen without forever chemicals and iridium

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

[Press-News.org] A clue to what lies beneath the bland surfaces of Uranus and NeptuneLayers of material that, like oil and water, don't mix can explain planets' unusual magnetic fields