Under strict embargo: 16:00 GMT Wednesday 1 January 2025

Peer reviewed

Observational study

Ancient people

Ancient DNA unlocks new understanding of migrations in the first millennium AD

Waves of human migration across Europe during the first millennium AD have been revealed using a more precise method of analysing ancestry with ancient DNA, in research led by the Francis Crick Institute.

Researchers can bring together a picture of how people moved across the world by looking at changes in their DNA, but this becomes a lot harder when historical groups of people are genetically very similar.

In research published today in Nature, researchers report a new data analysis method called Twigstats1, which allows the differences between genetically similar groups to be measured more precisely, revealing previously unknown details of migrations in Europe.

They applied the new method to over 1500 European genomes (a person’s complete set of DNA) from people who lived primarily during the first millennium AD (year 1 to 1000), encompassing the Iron Age, the fall of the Roman Empire, the early medieval ‘Migration Period’ and the Viking Age.

Germanic-speaking people move south in the early Iron Age

The Romans – whose empire was flourishing at the start of the first millennium – wrote about conflict with Germanic groups outside of the Empire’s frontiers.

Using the new method, the scientists revealed waves of these groups migrating south from Northern Germany or Scandinavia early in the first millennium, adding genetic evidence to the historical record.

This ancestry was found in people from southern Germany, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, and southern Britain, with one person in southern Europe carrying 100% Scandinavian-like ancestry.

The team showed that many of these groups eventually mixed with pre-existing populations. The two main zones of migration and interaction mirror the three main branches of Germanic languages, one of which stayed in Scandinavia, one of which became extinct, and another which formed the basis of modern-day German and English.

Finding a Roman gladiator?

In 2nd-4th century York in Britain, 25% of the ancestry of an individual who could have been a Roman soldier or slave gladiator came from early Iron Age Scandinavia. This highlights that there were people with Scandinavian ancestry in Britain earlier than the Anglo-Saxon and Viking periods which started in the 5th century AD.

Germanic-speaking people move north into Scandinavia before the Viking Age

The team then used the method to uncover a later additional northward wave of migration into Scandinavia at the end of the Iron Age (300-800 AD) and just before the Viking Age. They showed that many Viking Age individuals across southern Scandinavia carried ancestry from Central Europe.

A different type of biomolecular analysis of teeth found that people buried on the island of Öland, Sweden, who carried ancestry from Central Europe, had grown up locally, suggesting that this northward influx of people wasn’t a one-off, but a lasting shift in ancestry.

There is archaeological evidence for repeated conflicts in Scandinavia at this time, and the researchers speculate that this unrest may have played a role in driving movements of people, but more archaeological, genetic and environmental data is needed to shed light on the reasons why people moved into and around Scandinavia2.

Viking expansion out of Scandinavia

Historically, the Viking Age (c.800-1050 AD) is associated with people from Scandinavia raiding and settling throughout Europe.

The research showed that many people outside of Scandinavia during this time show a mix of local and Scandinavian ancestry, in support of the historical records.

For example, the team found some Viking Age individuals in the east (now present-day Ukraine and Russia) who had ancestry from present-day Sweden, and individuals in Britain who had ancestry from present-day Denmark.

In Viking Age mass graves in Britain, the remains of men who died violently showed genetic links to Scandinavia, suggesting they may have been executed members of Viking raiding parties.

Adding genetic evidence to historical accounts

Leo Speidel, first author, former postdoctoral researcher at the Crick and UCL and now group leader at RIKEN, Japan, said: “We already have reliable statistical tools to compare the genetics between groups of people who are genetically very different, like hunter-gatherers and early farmers, but robust analyses of finer-scale population changes, like the migrations we reveal in this paper, have largely been obscured until now.

“Twigstats allows us to see what we couldn’t before, in this case migrations all across Europe originating in the north of Europe in the Iron Age, and then back into Scandinavia before the Viking Age. Our new method can be applied to other populations across the world and hopefully reveal more missing pieces of the puzzle.”

Pontus Skoglund, Group Leader of the Ancient Genomics Laboratory at the Crick, and senior author, said: “The goal was a data analysis method that would provide a sharper lens for fine-scale genetic history. Questions that wouldn't have been possible to answer before are now within reach to us, so we now need to grow the record of ancient whole-genome sequences.”

Peter Heather, Professor of Medieval History at King’s College London, and co-author of the study, said: "Historical sources indicate that migration played some role in the massive restructuring of the human landscape of western Eurasia in the second half of the first millennium AD which first created the outlines of a politically and culturally recognisable Europe, but the nature, scale and even the trajectories of the movements have always been hotly disputed. Twigstats opens up the exciting possibility of finally resolving these crucial questions."

-ENDS-

For further information, contact: press@crick.ac.uk or +44 (0)20 3796 5252

Notes to Editors

Reference: Speidel, L.et al. (2025). High-resolution genomic history of early medieval Europe. Nature. 10.1038/s41586-024-08275-2.

How does Twigstats work?

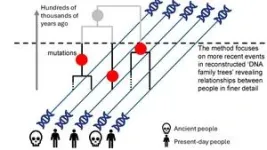

The more genetic mutations (differences in our DNA) that we share with another person, the closer we tend to be related. This is because we inherit our DNA through our ancestors, and so we inherit the same mutations that they also carried. Our DNA is therefore a proxy for the genetic ‘family trees’ that connect us all.

Over the past few years, scientists have found ways to directly reconstruct these genetic family trees by looking at how mutations are shared between people, connecting our DNA today with those of ancient people. These genetic family trees reveal how old mutations are and who they are shared by.

Twigstats directly looks at these genetic family trees to summarise who we have inherited our DNA from. This new approach looks at more recent mutations to reveal connections between people who lived closer together in time.

2. The period 300-800 AD is dynamic, and also one where the runic script and language changed across Scandinavia, as explored in the illustration.

About the Francis Crick Institute

The Francis Crick Institute is a biomedical discovery institute dedicated to understanding the fundamental biology underlying health and disease. Its work is helping to understand why disease develops and to translate discoveries into new ways to prevent, diagnose and treat illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, stroke, infections, and neurodegenerative diseases.

An independent organisation, its founding partners are the Medical Research Council (MRC), Cancer Research UK, Wellcome, UCL (University College London), Imperial College London and King’s College London.

The Crick was formed in 2015, and in 2016 it moved into a brand new state-of-the-art building in central London which brings together 1500 scientists and support staff working collaboratively across disciplines, making it the biggest biomedical research facility under a single roof in Europe.

http://crick.ac.uk/

END