(Press-News.org) Nitrogen is an essential component in the production of amino acids and nucleic acids — both necessary for cell growth and function. Although the atmosphere is composed of nearly 80% nitrogen, this nitrogen is in the form of dinitrogen (N2), which cannot be processed by most organisms. Atmospheric nitrogen must first be converted, or “fixed,” into a form that can be used by plants, often as ammonia.

There are only two ways of fixing nitrogen, one industrial and one biological. To better understand a key component of the biological process, University of California San Diego Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Akif Tezcan and Assistant Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Mark Herzik took a multi-pronged approach. Their work appears in Nature.

Thriving in a hostile environment

The industrial method is through the Haber-Bosch process, the advent of which in the early 20th century enabled the large-scale production of synthetic fertilizers, increased agricultural yields and helped the world population skyrocket. However, this process is energy-intensive, operating at very high temperatures and pressures. It also requires vast amounts of hydrogen, generated by burning fossil fuels, and is responsible for immense amounts of greenhouse gas emissions.

The biological route to fixing nitrogen is done by diazotrophs, nitrogen-fixing bacteria that contain an enzyme called nitrogenase. In contrast to the Haber-Bosch process, nitrogenase can be catalyzed at ambient pressures and temperatures and does not cause greenhouse gas emissions.

However, nitrogenase also requires large amounts of biochemical fuel, in the form of energy-producing adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Most diazotrophs make large amounts of ATP through cellular respiration by “burning” oxygen — even though nitrogenase is extremely sensitive to oxygen. Scientists have long wondered how a diazotroph, which needs to produce ATP by burning oxygen, also protects nitrogenase from being damaged by oxygen.

Diazotrophs have safety mechanisms in place; however, even with these protections in place, some oxygen penetration into the nitrogen-fixing cell is unavoidable. When this occurs, some diazotrophs employ a “method of last resort” to protect nitrogenase from destruction, called the conformational protection mechanism.

Here an iron-sulfur protein named FeSII senses increasing amounts of oxygen in the cell and binds to the nitrogenase enzyme complex, protecting it from damage and halting ammonia production. When the oxygen levels in the cell decrease, FeSII senses this again, disengages from the nitrogenase, and the ammonia production resumes.

Although scientists have long-known of the FeSII protein, the mechanism by which it protected nitrogenase from oxygen damage was not understood. To answer these questions, the researchers employed several techniques, which together provided detailed insight into how this mechanism worked.

A robust toolkit helps answer a longstanding question

First author Sarah Narehood is a joint graduate student who splits her time between the Tezcan and Herzik labs, learning both the behavior of nitrogenase while also capitalizing on developments in cryogenic electron microscopy (cryoEM) technology.

“This work truly highlights the interdisciplinary advances necessary to elucidate the structural dynamics of these complex natural systems,” stated Narehood.

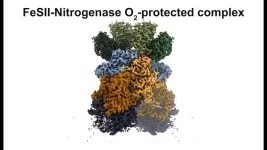

The team used a cryoEM method called single-particle reconstruction that enabled them to take near atomic-level snapshots of a mixture of nitrogenase proteins in the presence of FeSII. Doing this, they were able to visualize the structures, clearly revealing that FeSII sandwiches between two other nitrogenase proteins, gluing them together into filaments. This sandwiching blocked oxygen from accessing the sensitive metal cofactors of the nitrogenase proteins, while also inducing dormancy.

While this explained how nitrogenase was protected from oxygen exposure, it didn’t explain how FeSII was able to sense oxygen levels in the first place. To uncover this, the team used another technique called small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), using instrumentation located at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource.

The SAXS experiments showed that FeSII changes shape in the presence and absence of oxygen. In the presence of oxygen, FeSII’s shape fit perfectly between the other proteins, sandwiching them together into filaments. When oxygen levels drop, FeSII relaxes its structure, leading to dissociation of the filaments and re-activation of nitrogenase.

The researchers also employed an analytical ultracentrifuge, essentially the “Formula 1” of centrifuges because of how rapidly it spins. In an analytical ultracentrifuge, protein particles sediment to the bottom at varying speeds — heavier particles sediment faster, while lighter ones fall more slowly. This method allowed the researchers to analyze the masses of the different proteins as further confirmation that when FeSII senses oxygen, it glues the other nitrogenase proteins into larger assemblies and filaments.

Now that they have uncovered the mechanism through which FeSII protects nitrogenase from oxygen harm, the team wants to catch it in action in living cells. To do this, they want to employ cryoEM tomography, which will allow for the 3D visualization of the whole diazotrophic cell while it is in the process of fixing nitrogen, as well as the in vivo mechanism of oxygen protection.

Despite the fact that nitrogenase is one of the most critical enzymes in the biosphere, the molecular details of how it functions are still largely unknown. Resolving the details of the conformational protection mechanism provides an important piece of the puzzle, with significant practical implications.

“If the nitrogenase machinery can be encoded into plant cells so they do not require artificial fertilizers, it could mean less greenhouse gas emissions without sacrificing agricultural yield,” said Tezcan.

Something critically important for a growing population on a polluted planet.

Full list of authors: Sarah M. Narehood, Brian D. Cook, Suppachai Srisantitham, Vanessa H. Eng, Kelly L. McGuire, Mark A. Herzik and F. Akif Tezcan (all UC San Diego); Angela A. Shiau and R. David Britt (both UC Davis).

This research was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM148607, R35-GM138206 and R35-GM126961), NASA (80NSSC18M0093), the National Science Foundation (DGE-2038238), the Searle Scholars Program and the UC San Diego Interfaces Traineeship (T32 EB009380).

END

Scientists uncover key step in how diazotrophs “fix” nitrogen

A well-stocked toolbox helps researchers uncover the bacteria’s “last resort” mechanism

2025-01-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The hidden mechanics of earthquake ignition

2025-01-08

A new study has unravelled the hidden mechanics of how earthquakes ignite, shedding light on the mysterious transition from quiet, creeping motion to the violent ruptures that shake the Earth. Using cutting-edge experiments and innovative models, the research reveals that slow, silent stress release is a prelude and a necessary trigger for seismic activity. By incorporating the overlooked role of fault geometry, the study challenges long-held beliefs and offers a fresh perspective on how and when earthquakes begin. These findings not only deepen our understanding of nature’s ...

Scientists leverage artificial intelligence to fast-track methane mitigation strategies in animal agriculture

2025-01-08

BUSHLAND, Texas, Jan. 8, 2025 –A new study from USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and Iowa State University (ISU) reveals that generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) can help expedite the search for solutions to reduce enteric methane emissions caused by cows in animal agriculture, which accounts for about 33 percent of U.S. agriculture and 3 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

"Developing solutions to address methane emissions from animal agriculture is a critical priority. Our scientists continue to use innovative and data-driven strategies to help ...

Researchers unravel a novel mechanism regulating gene expression in the brain that could guide solutions to circadian and other disorders

2025-01-08

A collaborative effort between Mount Sinai and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has shed valuable light on how monoamine neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and now histamine help regulate brain physiology and behavior through chemical bonding of these monoamines to histone proteins, the core DNA-packaging proteins of our cells.

By uncovering how these histone modifications influence the brain, the team has identified a novel mechanism for controlling circadian gene expression and behavioral rhythms. ...

Discovery of 'Punk' and 'Emo' fossils challenges our understanding of ancient molluscs

2025-01-08

Researchers have unearthed two fossils, named Punk and Emo, revealing that ancient molluscs were more complex and adaptable than previously known.

Molluscs are one of life’s most diverse animal groups and analysis of the rare 430 million year old fossils is challenging long-held views on their early origins.

The fossils dating from the Silurian period were retrieved from Herefordshire and shed light on the molluscs’ complex evolutionary history and how they moved.

The discovery challenges the longstanding ...

Exposure to aircraft noise linked to worse heart function

2025-01-08

People who live close to airports and are exposed to high aircraft noise levels could be at greater risk of poor heart function, increasing the likelihood of heart attacks, life-threatening heart rhythms and strokes, according to a new study led by UCL (University College London) researchers.

The study, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), looked at detailed heart imaging data from 3,635 people who lived close to four major airports in England.

Within this group, the research team compared the hearts of those who lived in areas with higher aircraft noise with those who lived in lower aircraft noise areas.

They found that those who lived in ...

Deans of the University of Nottingham visited Korea University's College of Medicine

2025-01-08

Deans of the University of Nottingham Visited Korea University's College of Medicine

Korea University's College of Medicine Dean, Sung Bom Pyun, and Deans of the University of Nottingham; successfully held a researcher meeting program for 2 days from November 11th to 12th.

Fuve representative deans visited the University of Korea: Professor Claire Stewart, the Dean and Head of the School of Medicine at the University of Nottingham; Professor Nigel Mongan, Professor Alan McIntyre, Professor Srinivasan Madhusudan, and Professor Victoria James. They joined the program to conduct a tour and meeting with Korea University's researchers.

On ...

New study assesses wildfire risk from standing dead trees in Yellowstone National Park

2025-01-08

Standing dead trees in Yellowstone National Park are growing wildfire hazards, especially near park infrastructure. A new study published in Forest Ecosystems explores how these dead trees contribute to fire risk and threaten roads, buildings, and trails.

Dead trees, particularly those that remain standing, are a significant fire hazard. These trees—often caused by pests, diseases, and climate change—create a large amount of dry, combustible material. As temperatures rise and droughts intensify, the risk of wildfires increases, making it essential to understand how dead trees contribute to fire danger.

The team used a random forest classification model, a powerful ...

A new approach for improving hot corrosion resistance and anti-oxidation performance in silicide coating on niobium alloys

2025-01-08

The widely used nickel-based superalloys for turbine engine materials showed a limited-service temperature of only 1200℃, and did not exceed 1500℃ even when coated with thermal barrier coatings, which is urgent to develop the advanced thermal protection system for turbine engines with higher thrust-weight ratios. Niobium alloy coated with silicide coating is undoubtedly considered the most efficient method to reach long-term service, since it can form a dense SiO2 layer with self-healing ability at high temperatures. However, the single silicide coating has a strong tendency to crack vertically ...

UC San Diego to lead data hub of CDC-funded pandemic preparedness network

2025-01-08

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has selected University of California San Diego as one of three partner institutions to establish a groundbreaking pandemic preparedness initiative, the Community and Household Acute Respiratory Illness Monitoring (CHARM) Network. The new five-year cooperative agreement will help generate information on how respiratory viruses spread and provide insights into factors impacting susceptibility to respiratory illnesses. At UC San Diego, the cooperative agreement supports the $5.7 million project, “PREVENT: Preparedness through Respiratory Virus Epidemiology and Community Engagement” led by Louise Laurent, M.D., Ph.D., ...

Biomimetic teakwood structured environmental barrier coating

2025-01-08

The core message of the article is that researchers have developed an innovative technology in plasma spraying-physical vapor deposition known as alternating vapor/liquid phase deposition. By adjusting the arc current, researchers can finely control the evaporation and deposition of SiO2, and through a heat treatment process, achieve in-situ reactions that optimize the composition, structure, and nanoscale dimensions of the coating, creating an orderly arranged multi-layered teak-like biomimetic structure within it. They have conducted an in-depth analysis of the complex deposition mechanisms involved in this process. This new teak-like biomimetic structure coating is expected ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New tool reveals the secrets of HIV-infected cells

HMH scientists calculate breathing-brain wave rhythms in deepest sleep

Electron microscopy shows ‘mouse bite’ defects in semiconductors

Ochsner Children's CEO joins Make-A-Wish Board

Research spotlight: Exploring the neural basis of visual imagination

Wildlife imaging shows that AI models aren’t as smart as we think

Prolonged drought linked to instability in key nitrogen-cycling microbes in Connecticut salt marsh

Self-cleaning fuel cells? Researchers reveal steam-powered fix for ‘sulfur poisoning’

Bacteria found in mouth and gut may help protect against severe peanut allergic reactions

Ultra-processed foods in preschool years associated with behavioural difficulties in childhood

A fanged frog long thought to be one species is revealing itself to be several

Weill Cornell Medicine selected for Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award

Largest high-precision 3D facial database built in China, enabling more lifelike digital humans

SwRI upgrades facilities to expand subsurface safety valve testing to new application

Iron deficiency blocks the growth of young pancreatic cells

Selective forest thinning in the eastern Cascades supports both snowpack and wildfire resilience

A sea of light: HETDEX astronomers reveal hidden structures in the young universe

Some young gamers may be at higher risk of mental health problems, but family and school support can help

Reduce rust by dumping your wok twice, and other kitchen tips

High-fat diet accelerates breast cancer tumor growth and invasion

Leveraging AI models, neuroscientists parse canary songs to better understand human speech

Ultraprocessed food consumption and behavioral outcomes in Canadian children

The ISSCR honors Dr. Kyle M. Loh with the 2026 Early Career Impact Award for Transformative Advances in Stem Cell Biology

The ISSCR honors Alexander Meissner with the 2026 ISSCR Momentum Award for exceptional work in developmental and stem cell epigenetics

The ISSCR honors stem cell COREdinates and CorEUstem with the 2026 ISSCR Public Service Award

Minimally invasive procedure effectively treats small kidney cancers

SwRI earns CMMC Level 2 cybersecurity certification

Doctors and nurses believe their own substance use affects patients

Life forms can planet hop on asteroid debris – and survive

Sylvia Hurtado voted AERA President-Elect; key members elected to AERA Council

[Press-News.org] Scientists uncover key step in how diazotrophs “fix” nitrogenA well-stocked toolbox helps researchers uncover the bacteria’s “last resort” mechanism