(Press-News.org) UNSW engineers have demonstrated a well-known quantum thought experiment in the real world. Their findings deliver a new and more robust way to perform quantum computations – and they have important implications for error correction, one of the biggest obstacles standing between them and a working quantum computer.

Quantum mechanics has puzzled scientists and philosophers for more than a century. One of the most famous quantum thought experiments is that of the “Schrödinger’s cat” – a cat whose life or death depends on the decay of a radioactive atom.

According to quantum mechanics, unless the atom is directly observed, it must be considered to be in a superposition – that is, being in multiple states at the same time – of decayed and not decayed. This leads to the troubling conclusion that the cat is in a superposition of dead and alive.

“No one has ever seen an actual cat in a state of being both dead and alive at the same time, but people use the Schrödinger’s cat metaphor to describe a superposition of quantum states that differ by a large amount,” says UNSW Professor Andrea Morello, leader of the team that conducted the research, published recently in the journal Nature Physics.

Atomic cat

For this research paper, Prof. Morello’s team used an atom of antimony, which is much more complex than standard ‘qubits’, or quantum building blocks.

“In our work, the ‘cat’ is an atom of antimony,” says Xi Yu, lead author of the paper.

“Antimony is a heavy atom, which possesses a large nuclear spin, meaning a large magnetic dipole. The spin of antimony can take eight different directions, instead of just two. This may not seem much, but in fact it completely changes the behaviour of the system. A superposition of the antimony spin pointing in opposite directions is not just a superposition of ‘up’ and ‘down’, because there are multiple quantum states separating the two branches of the superposition.”

This has profound consequences for scientists working on building a quantum computer using the nuclear spin of an atom as the basic building block.

“Normally, people use a quantum bit, or ‘qubit’ – an object described by only two quantum states – as the basic unit of quantum information,” says co-author Benjamin Wilhelm.

“If the qubit is a spin, we can call ‘spin down’ the ‘0’ state, and ‘spin up’ the ‘1’ state. But if the direction of the spin suddenly changes, we have immediately a logical error: 0 turns to 1 or vice versa, in just one go. This is why quantum information is so fragile.”

But in the antimony atom that has eight different spin directions, if the ‘0’ is encoded as a ‘dead cat’, and the ‘1’ as an ‘alive cat’, a single error is not enough to scramble the quantum code.

“As the proverb goes, a cat has nine lives. One little scratch is not enough to kill it. Our metaphorical ‘cat’ has seven lives: it would take seven consecutive errors to turn the ‘0’ into a ‘1’! This is the sense in which the superposition of antimony spin states in opposite directions is ‘macroscopic’ – because it’s happening on a larger scale, and realises a Schrödinger cat,” explains Yu.

Scalable technology

The antimony cat is embedded inside a silicon quantum chip, similar to the ones we have in our computers and mobile phones, but adapted to give access to the quantum state of a single atom. The chip was fabricated by UNSW’s Dr Danielle Holmes, while the atom of antimony was inserted in the chip by colleagues at the University of Melbourne.

“By hosting the atomic ‘Schrödinger cat’ inside a silicon chip, we gain an exquisite control over its quantum state – or, if you wish, over its life and death,” says Dr Holmes.

“Moreover, hosting the ‘cat’ in silicon means that, in the long term, this technology can be scaled up using similar methods as those we already adopt to build the computer chips we have today.”

The significance of this breakthrough is that it opens the door to a new way to perform quantum computations. The information is still encoded in binary code, ‘0’ or ‘1’, but there is more ‘room for error’ between the logical codes.

“A single, or even a few errors, do not immediately scramble the information,” Prof. Morello says.

“If an error occurs, we detect it straight away, and we can correct it before further errors accumulate. To continue the ‘Schrödinger cat’ metaphor, it’s as if we saw our cat coming home with a big scratch on his face. He’s far from dead, but we know that he got into a fight; we can go and find who caused the fight, before it happens again and our cat gets further injuries.”

The demonstration of quantum error detection and correction – a ‘Holy Grail’ in quantum computing – is the next milestone that the team will address.

The work was the result of a vast international collaboration. Several authors from UNSW Sydney, plus colleagues at the University of Melbourne, fabricated and operated the quantum devices. Theory collaborators in the USA, at Sandia National Laboratories and NASA Ames, and Canada, at the University of Calgary, provided precious ideas on how to create the cat, and how to assess its complicated quantum state.

“This work is a wonderful example of open-borders collaboration between world-leading teams with complementary expertise,” says Prof. Morello.

END

This metaphorical cat is both dead and alive – and it will help quantum engineers detect computing errors

2025-01-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Digitizing hope: Collaboration helps preserve a species on the brink of extinction

2025-01-14

The vaquita, which means “little cow” in Spanish, is the world’s smallest porpoise and most endangered marine mammal. They also have the smallest range of any marine mammal; about 1,500 square miles within the northern Gulf of California. Since 1997, vaquitas have experienced a dramatic population loss from about 600 individuals to an estimate of less than 10 animals to date. At this current rate, vaquitas are expected to become extinct imminently.

The vaquita’s decline is caused by entanglement in illegal gillnets used to fish totoaba, an endangered species prized for its swim bladder. Despite a gillnet ban and conservation efforts, ...

The Dark Side of the ocean: New giant sea bug species named after Darth Vader

2025-01-14

Giant isopods of the genus Bathynomus, which can reach more than 30 cm in length, are known as bọ biển or “sea bugs” in Vietnam. For the first time, one such species was described from Vietnamese waters and named Bathynomus vaderi. The name “vaderi” is inspired by the appearance of its head, which closely resembles the distinctive and iconic helmet of Darth Vader, the most famous Sith Lord of Star Wars.

Bathynomus vaderi belongs to a group known as “supergiants,” reaching lengths of 32.5 cm and weighing over a kilogram. So far, this ...

Roman urbanites followed medical recommendations for weaning babies

2025-01-14

Babies were weaned earlier in cities in the Roman Empire than in smaller and more rural communities, according to a study of ancient teeth. Urban weaning patterns more closely hewed to guidelines from ancient Roman physicians, mirroring contemporary patterns of adherence to medical experts in urban and rural communities.

Roman health authorities recommended breastfeeding babies for two years. Carlo Cocozza and colleagues were interested in how ancient Romans actually fed their babies in varying settlement types. Carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios in dentine from the first permanent molars record ...

Strength connected to sexual behavior of women as well as men

2025-01-14

VANCOUVER, Wash. – While many studies have looked at possible evolutionary links between men’s strength and sexual behavior, a Washington State University study included data on women with a surprising result. Women, as well as men, who had greater upper body strength tended to have more lifetime sexual partners compared to their peers.

The study, published in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior, was designed to test evolutionary theories for human sexual dimorphism—namely that in early human history there was likely a reproductive advantage selecting for men’s greater upper body strength.

Another ...

Eating pork linked with better handgrip strength, vegetable intake in Korean older adults

2025-01-14

New research1 underscores the potential role of pork consumption in supporting dietary and muscle health in Korean older adults. Older adults are a nutritionally vulnerable population who often face unique challenges, including meeting daily protein and micronutrient requirements.

The study,* conducted through a collaborative partnership between researchers from Gachon University in South Korea, Tufts University, Think Healthy Group, LLC, and other leading institutions, suggests that pork consumption may be positively linked to nutrient intake, diet quality and handgrip strength—an indicator of overall muscle strength in older adults.

Using data from more than 2,000 ...

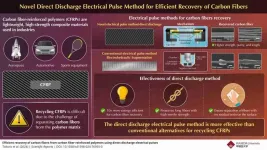

Direct discharge electrical pulses for carbon fiber recycling

2025-01-14

The world is hurtling rapidly towards a developed future, and carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRPs) play a key role in enabling technological and industrial progress. These composite materials are lightweight and highly strong, making them desirable for applications in various fields, including aviation, aerospace, automotive, wind power generation, and sports equipment.

However, recycling CFRPs presents a significant challenge, with waste management being a pressing issue. Conventional recycling methods ...

Scientists uncover rapid-acting, low-side-effect antidepressant target

2025-01-14

The global burden of anxiety- and depression-related disorders is on the rise. While multiple drugs have been developed to treat these conditions, current medications have several limitations, including slow action and adverse effects with long-term use. This underscores the urgent need for novel, rapidly-acting therapeutic agents with minimal side effects.

The delta opioid receptor (DOP) plays a key role in mood regulation, making it a promising target for therapeutic intervention. Studies have shown that selective DOP agonists (compounds that activate DOP), such as SNC80 ...

Diamond continues to shine: new properties discovered in diamond semiconductors

2025-01-14

CLEVELAND and CHAMPAIGN-URBANA, ILL.—Diamond, often celebrated for its unmatched hardness and transparency, has emerged as an exceptional material for high-power electronics and next-generation quantum optics. Diamond can be engineered to be as electrically conductive as a metal, by introducing impurities such as the element boron.

Researchers from Case Western Reserve University and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have now discovered another interesting property in diamonds with added boron, known as boron-doped diamonds. Their findings could pave the way for new types ...

Researchers find the key to Artificial Intelligence’s learning power – an inbuilt, special kind of Occam’s razor

2025-01-14

A new study from Oxford University has uncovered why the deep neural networks (DNNs) that power modern artificial intelligence are so effective at learning from data. The new findings demonstrate that DNNs have an inbuilt ‘Occam's razor,’ meaning that when presented with multiple solutions that fit training data, they tend to favour those that are simpler. What is special about this version of Occam’s razor is that the bias exactly cancels the exponential growth of the number of possible solutions with complexity. The study has been published ...

Genetic tweak optimizes drug-making cells by blocking buildup of toxic byproduct

2025-01-14

An international team of researchers led by the University of California San Diego has developed a new strategy to enhance pharmaceutical production in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, which are commonly used to manufacture protein-based drugs for treating cancer, autoimmune diseases and much more. By knocking out a gene circuit responsible for producing lactic acid—a metabolite that makes the cells’ environment toxic—researchers eliminate a primary hurdle in developing cells that can produce higher amounts of pharmaceuticals like Herceptin and Rituximab, without compromising their growth or energy production.

The research, published on Jan. 14 in Nature Metabolism, ...