(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Many materials store information about what has happened to them in a sort of material memory, like wrinkles on a once crumpled piece of paper. Now, a team led by Penn State physicists has uncovered how, under specific conditions, some materials seemingly violate underlying mathematics to store memories about the sequence of previous deformations. According to the researchers, the method, described in a paper appearing today (Jan. 29) in the journal Science Advances, could inspire new ways to store information in mechanical systems, from combination locks to computing.

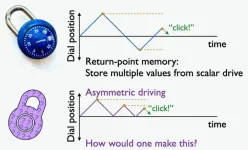

One way some materials form memories is called return-point memory, which operates much like a single dial combination lock, according to Nathan Keim, associate professor of physics in the Penn State Eberly College of Science and leader of the research team. With a lock, rotating the dial clockwise and counterclockwise in a particular sequence yields a result — the lock opening — that depends on how the dial was moved. Likewise, for materials with return-point memory, alternating between positive and negative deformations can leave a memory of the sequence that researchers can read or erase.

“The same underlying mechanism or mathematics of this memory formation can describe systems from the magnetization of computer hard drives to damage in solid rock,” Keim said, noting that his research group recently showed that the same math also describes memories stored in disordered solids, in which the arrangement of particles seems random but actually contains details about past deformations.

Return-point memory relies on the alternating of direction of the external force, or “driving,” such as the alternating of positive or negative magnetic field or pulling on a material from one side and then the other. However, materials should not be able to form return-point memory when the force only occurs in one direction. For example, Keim said, a bridge might sag slightly as cars drive over it, but it doesn’t curve upwards once the cars are gone.

“The mathematical theorems for return-point memory say that we can’t store a sequence if we only have this ‘asymmetrical’ driving in one direction,” Keim said. “If the combination lock dial can’t go past zero when turning counterclockwise, it only stores one number in the combination. But we found a special case when this kind of asymmetrical driving can, in fact, encode a sequence.”

The researchers performed a series of computer simulations to explore the conditions under which a sequence could be encoded in a material. They manipulated a variety of factors, including the magnitude and orientation of the external driving force as well as how it is generated, to see how they impact memory formation and the length of the encoded sequence. To do so, the researchers boiled down the components of the system — such as the particles in a solid or the microscopic domains in a magnet — into abstract elements called hysterons.

“Hysterons are elements of a system that may not immediately respond to external conditions, and can stay in a past state,” said Travis Jalowiec, an undergraduate at the time of the research who earned his bachelor’s degree in physics at Penn State and an author of the paper. “Like how parts of a combination lock reflect the previous positions of the dial, and not where the dial is now. In our model, hysterons have two possible states and can work with or against each other, and this generalized model makes it applicable to as many systems as possible.”

The hysterons in the model interact either in a cooperative way, where a change in one encourages a change in the other, or in a non-cooperative “frustrated” way, where a change in one discourages a change in the other. Frustrated hysterons, Jalowiec explained, are the key to forming and recovering a sequence in a system with asymmetric driving.

“A good example of frustration is a bendy straw, which has a series of little bellows that can be collapsed or popped open,” Keim said. “If you pull on the ends of the straw a tiny amount and stop, one will pop open, and it being open means that the others do not. The change in one relieves the stress in the system.

The researchers found that systems with cooperative interactions could only encode a sequence if the driving was symmetric — with alternating directions. However, just a single pair of frustrated hysterons was enough to produce an encoded sequence with asymmetric driving, so long as other conditions are met.

“Finding a pair of frustrated hysterons in a real material has been elusive,” Keim said. “It’s hard to observe, because often the signature of frustration is that something doesn’t happen. The behavior we found is rare, but it would stand out like a sore thumb in a real material, so it gives us a new way to look for and study materials with frustration. But more immediately, we think this is a way to design artificial systems with this special kind of memory, starting with the simplest mechanical systems not much more complicated than a bendy straw and hopefully working up to something like an asymmetrical combination lock.”

The researchers say these results could inspire new ways to store, recall and erase information in materials and mechanical systems.

“One key property of this memory is that it’s guaranteed to store both the largest deformation and the most recent deformation,” Keim said. “If you can make a system that stores a sequence of memories, you can use it like a combination lock to verify a specific history, or you could recover diagnostic or forensic information about the past. There is increasing interest in mechanical systems that sense their environments, perform computations and respond or adapt without ever using electricity. A better understanding of memory expands these possibilities.”

In addition to Keim and Jalowiec, the research team includes Chloe Lindeman, graduate student at the University of Chicago at the time of the research, now a Miller Postdoctoral Fellow at Johns Hopkins University. Funding from the U.S. Department of Energy, Penn State Schreyer Honors College and Penn State Student Engagement Network supported this work.

END

Materials can remember a sequence of events in an unexpected way

New study identifies unexpected way to store, recall and erase the sequence of a material’s previous deformations

2025-01-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NewsGuard: Study finds no bias against conservative news outlets

2025-01-29

[Vienna, 29.01.2025]—A recent study evaluating the NewsGuard database, a leading media reliability rating service, has found no evidence supporting the allegation that NewsGuard is biased against conservative news outlets. Actually, the results suggest it’s unlikely that NewsGuard has an inherent bias in how it selects or rates right-leaning sources in the US, where trustworthiness is especially low.

“It seems unlikely that NewsGuard has an inherent bias against conservative sources, both in selecting and giving them lower ratings. Instead, the US media system is flooded with right-wing sources that tend to not adhere to professional ...

New tool can detect fast-spreading SARS-COV-2 variants before they take off

2025-01-29

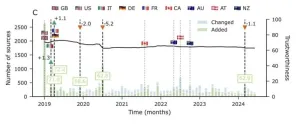

By analysing millions of viral genome sequences from around the world, a team of scientists, led by the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) and the University of Pittsburgh, uncovered the specific mutations that give SARS-CoV-2 a ‘turbo boost’ in its ability to spread.

“Among thousands of SARS-CoV-2 mutations, we identified a small number that increase the virus’ ability to spread,” said Professor Matthew McKay, a Laboratory Head at the Doherty Institute and ARC Future Fellow in the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at the University of Melbourne, and co-lead author of the ...

Berkeley Lab helps explore mysteries of Asteroid Bennu

2025-01-29

During the past year, there’s been an unusual set of samples at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab): material gathered from the 4.5-billion-year-old asteroid Bennu when it was roughly 200 million miles from Earth.

Berkeley Lab is one of more than 40 institutions investigating Bennu’s chemical makeup to better understand how our solar system and planets evolved. In a new study published today in the journal Nature, researchers found evidence that Bennu comes from an ancient wet world, with some material from the coldest regions of the solar system, likely beyond the orbit of ...

Princeton Chem discovers that common plastic pigment promotes depolymerization

2025-01-29

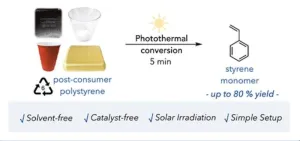

It turns out that the black plastic lid atop your coffee cup has a superpower. And the Stache Lab at Princeton Chemistry, which uncovered it, is exploiting that property to recycle at least two major types of plastic.

Their startling mechanism for promoting depolymerization relies on an additive that many plastics already contain: a pigment called carbon black that gives plastic its black color. Through a process called photothermal conversion, intense light is focused on plastic containing the pigment that jumpstarts the degradation.

So far, researchers have shown that carbon black can depolymerize polystyrene and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), two of the least recycled plastics in the planet’s ...

AI-driven multi-modal framework revolutionizes protein editing for scientific and medical breakthroughs

2025-01-29

Researchers from Zhejiang University and HKUST (Guangzhou) have developed a cutting-edge AI model, ProtET, that leverages multi-modal learning to enable controllable protein editing through text-based instructions. This innovative approach, published in Health Data Science, bridges the gap between biological language and protein sequence manipulation, enhancing functional protein design across domains like enzyme activity, stability, and antibody binding.

Proteins are the cornerstone of biological functions, and their precise modification holds immense potential for medical therapies, synthetic biology, and biotechnology. While traditional protein editing methods ...

Traces of ancient brine discovered on the asteroid Bennu contain minerals crucial to life

2025-01-29

A new analysis of samples from the asteroid Bennu, NASA’s first asteroid sample captured in space and delivered to Earth, reveals that evaporated water left a briny broth where salts and minerals allowed the elemental ingredients of life to intermingle and create more complex structures. The discovery suggests that extraterrestrial brines provided a crucial setting for the development of organic compounds.

In a paper published today, Jan. 29, in the journal Nature, scientists at the Smithsonian’s National Museum ...

Most mental health crisis services did not increase following 988 crisis hotline launch

2025-01-29

The launch of the nation’s 988 mental health hotline did not coincide with significant and equitable growth in the availability of most crisis services, except for a small increase in peer support services, according to a new RAND study.

Examining reports from thousands of mental health treatment facilities about the types of crisis services offered before and after the July 2022 rollout of the 988 hotline, researchers found that there was an increase in peer support services, a significant decrease in psychiatric walk-in services, and small declines in mobile crisis response and suicide prevention services.

Significant ...

D-CARE study finds no differences between dementia care approaches on patient behavioral symptoms or caregiver strain

2025-01-29

New research comparing different approaches to dementia care for people with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias found no significant differences in patient behavioral symptoms or caregiver strain, whether delivered through a health system, provided by a community-based organization, or as usual care over an 18-month period.

However, the Dementia Care Study, also known as D-CARE, also found that caregiver self-efficacy—a measurement of caregivers’ confidence in managing dementia-related challenges and accessing support — improved in both the health-system and community-based ...

Landmark genetic study: Fresh shoots of hope on the tree of life

2025-01-29

In the most comprehensive global analysis of genetic diversity ever undertaken, an international team of scientists has found that the genetic diversity is being lost across the globe but that conservation efforts are helping to safeguard species.

The landmark study, published in the pre-eminent scientific journal Nature, was led by Associate Professor Catherine Grueber from the School of Life and Environmental Sciences and a team of researchers from countries including the UK, Sweden, Poland, Spain, Greece and China.

The data spans more than three decades (from 1985-2019) and looks at 628 species of animals, plants and fungi across all terrestrial ...

Discovery of a unique drainage and irrigation system that gave way to the “Neolithic Revolution” in the Amazon

2025-01-29

A pre-Columbian society in the Amazon developed a sophisticated agricultural engineering system that allowed them to produce maize throughout the year, according to a recent discovery by a team of researchers from the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA-UAB) and the Department of Prehistory at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, (Spain); the Universities of Exeter, Nottingham, Oxford, Reading and Southampton (UK); the University of São Paulo (Brazil) and Bolivian collaborators. This finding contradicts previous theories that dismissed the possibility of intensive monoculture agriculture in the region.

The study, published today ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How sleep disruption impairs social memory: Oxytocin circuits reveal mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities

Natural compound from pomegranate leaves disrupts disease-causing amyloid

A depression treatment that once took eight weeks may work just as well in one

New study calls for personalized, tiered approach to postpartum care

The hidden breath of cities: Why we need to look closer at public fountains

Rewetting peatlands could unlock more effective carbon removal using biochar

Microplastics discovered in prostate tumors

ACES marks 150 years of the Morrow Plots, our nation's oldest research field

Physicists open door to future, hyper-efficient ‘orbitronic’ devices

$80 million supports research into exceptional longevity

Why the planet doesn’t dry out together: scientists solve a global climate puzzle

Global greening: The Earth’s green wave is shifting

You don't need to be very altruistic to stop an epidemic

Signs on Stone Age objects: Precursor to written language dates back 40,000 years

MIT study reveals climatic fingerprints of wildfires and volcanic eruptions

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

Exposure to alcohol-related social media content and desire to drink among young adults

Access to dialysis facilities in socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities

Dietary patterns and indicators of cognitive function

New study shows dry powder inhalers can improve patient outcomes and lower environmental impact

[Press-News.org] Materials can remember a sequence of events in an unexpected wayNew study identifies unexpected way to store, recall and erase the sequence of a material’s previous deformations