(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – Turning environmental waste into useful chemical resources could solve many of the inevitable challenges of our growing amounts of discarded plastics, paper and food waste, according to new research.

In a significant breakthrough, researchers from The Ohio State University have developed a technology to transform materials like plastics and agricultural waste into syngas, a substance most often used to create chemicals and fuels like formaldehyde and methanol.

Using simulations to test how well the system could break down waste, scientists found that their approach, called chemical looping, could produce high-quality syngas in a more efficient manner than other similar chemical techniques. Altogether, this refined process saves energy and is safer for the environment, said Ishani Karki Kudva, lead author of the study and a doctoral student in chemical and biomolecular engineering at Ohio State.

“We use syngas for important chemicals that are required in our day-to-day life,” said Kudva. “So improving its purity means that we can utilize it in a variety of new ways.”

Today, most commercial processes create syngas that is about 80 to 85% pure, but Kudva’s team achieved a purity of around 90% in a process that takes only a few minutes.

This study builds on decades of previous research at Ohio State, led by Liang-Shih Fan, a distinguished university professor in chemical and biomolecular engineering who advised the study. This previous research used chemical looping technology to turn fossil fuels, sewer gas and coal into hydrogen, syngas and other useful products.

In the new study, the system consists of two reactors: a moving bed reducer where waste is broken down using oxygen provided by metal oxide material, and a fluidized bed combustor that replenishes the lost oxygen so that the material can be regenerated. The study showed that with this waste-to-fuel system, the reactors could run up to 45% more efficiently and still produce about 10% cleaner syngas than other methods.

The study was recently published in the journal Energy and Fuels.

According to a report by the Environmental Protection Agency, 35.7 million tons of plastics were generated in the U.S. in 2018, of which about 12.2% is municipal solid waste, such as plastic containers, bags, appliances, furniture, agricultural residue, paper and food.

Unfortunately, since plastics are resistant to decomposition, they can persist in nature for long periods and can be difficult to completely break down and recycle. Conventional waste management, such as landfilling and incineration, also poses risks to the environment.

Now, the researchers are presenting an alternative solution to help curb pollution. For example, by measuring how much carbon dioxide their system would pump out compared to conventional processes, findings revealed it could reduce carbon emissions by up to 45%.

Their project’s design is just one of many in the chemical sector being driven by the urgent need for more sustainable technologies, said Shekhar Shinde, co-author of the study and a doctoral student in chemical and biomolecular engineering at Ohio State.

In this study’s case, their work could help drastically reduce society’s dependence on fossil fuels.

“There has been a drastic shift in terms of what was done before and what people are trying to do now in terms of decarbonizing research,” he said.

While earlier technologies could only filter biomass waste and plastics separately, this team’s technology also has the potential to handle multiple types of materials at once by continuously blending the conditions needed to convert them, noted the study.

Once the team’s simulations yield more data, they eventually hope to test the system’s market capabilities by conducting experiments over a longer time frame with other unique components.

“Expanding the process to include the municipal solid waste that we get from recycling centers is our next priority,” Kudva said. “The work in the lab is still going on with respect to commercializing this technology and decarbonizing the industry.”

Other Ohio State co-authors include Rushikesh K. Joshi, Tanay A. Jawdekar, Sudeshna Gun, Sonu Kumar, Ashin A Sunny, Darien Kulchytsky and Zhuo Cheng. The study was supported by Buckeye Precious Plastic.

#

Contact: Ishani Karki Kudva, Kudva.8@osu.edu,

Liang-Shih Fan, Fan.1@osu.edu

Written by: Tatyana Woodall, Woodall.52@osu.edu

END

Working dogs take a day to adjust to the change in routine caused by Daylight Savings Time, whereas pet dogs and their owners seem to be unaffected, according to a study publishing January 29, 2025 in the open-access journal PLOS One by Lavania Nagendran, Ming Fei Li and colleagues at the University of Toronto, Canada.

Daylight Savings Time (DST) is used by many countries to maintain the alignment between daylight hours and human activity patterns, by setting clocks forward one hour in the spring and back one hour in the autumn. Previous research has shown that DST can disrupt ...

In a new linguistic analysis, reviews of movies with female-dominated casts were found to have significantly higher levels of sexism than reviews of movies with male-dominated casts. Jad Doughman and Wael Khreich of the American University of Beirut, Lebanon, present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS One, on January 29, 2025.

Prior research suggests that negative movie reviews can affect actors’ finances, career paths, and mental well-being, while also influencing the broader media landscape. However, studies of gender bias in reviews have traditionally relied on movie ratings or box-office ...

When exercising in gyms, women face barriers across various domains, including physical appearance and body image, gym attire, the physical gym environment, and interactions with others, according to a study published January 29, 2025, in the open-access journal PLOS One by Emma Cowley from the SHE Research Centre, TUS, Ireland, and Jekaterina Schneider from the University of the West of England, U.K.

Exercise significantly improves physical, mental, and psychosocial health. Recent research indicates that women who engage in regular exercise experience greater health benefits than men, including lower incidence of all-cause mortality and reduced ...

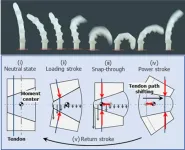

Seoul National University College of Engineering announced that a research team led by Professor Kyu-Jin Cho (Director of the Soft Robotics Research Center) from the Department of Mechanical Engineering took inspiration from principles found in nature and developed the "Hyperelastic Torque Reversal Mechanism (HeTRM)," which enables robots made from rubber-like soft materials to perform rapid and powerful movements. This study was published in the prestigious international journal Science Robotics on January 29.

The mantis shrimp delivers a punch ...

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 19:00 GMT / 14:00 ET, WEDNESDAY 29 JANUARY 2025

Quantum-inspired computing drives major advance in simulating turbulence

Researchers at the University of Oxford have pioneered a new approach to simulate turbulent systems, based on probabilities. The findings have been published today (29 January) in the journal Science Advances.

Predicting the dynamics of turbulent fluid flows has long been a central goal for scientists and engineers. Yet, even with modern computing technology, direct and accurate simulation of all but the simplest turbulent flows remains impossible.

This is due to turbulence being ...

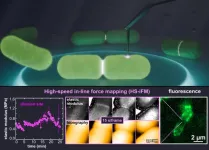

Light and electron microscopy have distinct limitations. Light microscopy makes it difficult to resolve smaller and smaller features, and electron microscopy resolves small structures, but samples must be meticulously prepared, killing any live specimens.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a technique originally developed to assess the physical and mechanical properties of materials at extremely high resolutions, but the imaging speeds aren’t fast enough (e.g. several minutes per frame) to capture relevant data for living biological samples. In contrast, another method, high-speed AFM (HS-AFM), is fast but cannot measure mechanical properties. Understanding ...

An international team of scientists has discovered the anti-icing secret of polar bear fur – something that allows one of the planet’s most iconic animals to survive and thrive in one of its most punishing climates. That secret? Greasy hair.

After some polar sleuthing, which involved scrutiny of hair collected from six polar bears in the wild, the scientists homed in on the hair “sebum” (or grease) as the all-important protectant. This sebum, which is made up of cholesterol, diacylglycerols, and fatty acids, makes it very hard for ice to attach to their fur.

While this finding ...

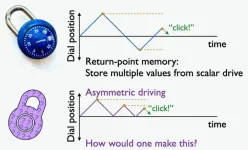

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Many materials store information about what has happened to them in a sort of material memory, like wrinkles on a once crumpled piece of paper. Now, a team led by Penn State physicists has uncovered how, under specific conditions, some materials seemingly violate underlying mathematics to store memories about the sequence of previous deformations. According to the researchers, the method, described in a paper appearing today (Jan. 29) in the journal Science Advances, could inspire new ways to store information in ...

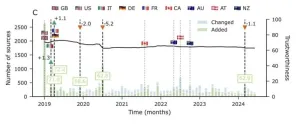

[Vienna, 29.01.2025]—A recent study evaluating the NewsGuard database, a leading media reliability rating service, has found no evidence supporting the allegation that NewsGuard is biased against conservative news outlets. Actually, the results suggest it’s unlikely that NewsGuard has an inherent bias in how it selects or rates right-leaning sources in the US, where trustworthiness is especially low.

“It seems unlikely that NewsGuard has an inherent bias against conservative sources, both in selecting and giving them lower ratings. Instead, the US media system is flooded with right-wing sources that tend to not adhere to professional ...

By analysing millions of viral genome sequences from around the world, a team of scientists, led by the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) and the University of Pittsburgh, uncovered the specific mutations that give SARS-CoV-2 a ‘turbo boost’ in its ability to spread.

“Among thousands of SARS-CoV-2 mutations, we identified a small number that increase the virus’ ability to spread,” said Professor Matthew McKay, a Laboratory Head at the Doherty Institute and ARC Future Fellow in the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at the University of Melbourne, and co-lead author of the ...