(Press-News.org) BOZEMAN – In a new publication in the journal Nature Communications, Montana State University scientists in College of Agriculture highlight fresh knowledge of how ancient microorganisms adapted from a low-oxygen prehistoric environment to the one that exists today. The work builds on more than two decades of scientific research in Yellowstone National Park by MSU professor Bill Inskeep.

The article, titled “Respiratory Processes of Early-evolved Hyperthermophiles in Sulfidic and Low-oxygen Geothermal Microbial Communities” was published Jan. 2. Authors Inskeep, a professor in the Department of Land Resources and Environmental Sciences, and Mensur Dlakic, an associate professor in the Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology, compared the heat-loving organisms in two Yellowstone thermal features, Conch Spring and Octopus Spring, located in the park’s Lower Geyser Basin.

Inskeep and Dlakic selected the locations because they are geochemically similar, with one notable exception: Conch Spring is higher in sulfide and oxygen compared to Octopus Spring. For that reason, they were able to focus on two contrasting thermal environments with both low and high levels of oxygen.

Three types of thermophilic microbes – organisms that thrive in high-temperature environments – were found in both springs, whose temperatures hover around 190 degrees Fahrenheit. The paper states that microbes’ lifestyles in their respective environments can shed light on how life evolved prior to and through the Great Oxidation Event, the period roughly 2.4 billion years ago when Earth’s atmosphere transitioned from having almost no oxygen to the nearly 20% oxygen content it has today.

“When oxygen started to increase in the environment, these thermophiles were likely important in the origin of microbial life,” said Inskeep, who has conducted research in Yellowstone since 1999. “There was an evolution of organisms that utilized oxygen. Octopus has more oxygen and sure enough, there's more aerobic organisms there. These environments have different casts of characters.”

The microorganisms that Inskeep and Dlakic studied are found within “streamers” that live in the rapid stream currents . Streamers, which look like small kelp plants, attach to rocks and other objects within the spring and grow filaments that ‘wiggle’ in the current.

While visually similar, the streamers in Conch and Octopus springs hosted very different collections of microbes. Although three species of microbes were common to both springs, the higher-oxygen Octopus Spring had much greater diversity. That offers insight into how they evolved to thrive in a higher-oxygen world, the scientists said.

The authors compared respiratory genes found in the microbes of Conch versus Octopus Spring. Genes adapted to very low oxygen were “highly expressed, meaning they were more active, in Conch Spring. Conversely, the organisms in Octopus Spring were expressing genes adapted to higher oxygen levels, likely more important as oxygen levels increased throughout the Great Oxidation Event.

In his three decades at MSU, Inskeep has collected extensive data from Yellowstone, but he said there is always more to learn and more questions to ask. In 2020, he and Dlakic received a grant from the National Science Foundation’s Opportunities for Promoting Understanding through Synthesis program to study Yellowstone’s thermophiles, and their collaboration has continued to illuminate previously unknown aspects of how life on Earth came to be.

MSU’s placement in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem also makes it ideally placed to conduct this type of research, Inskeep said.

“It would be very difficult to reproduce this kind of an experiment in the laboratory; imagine trying to reate hot-water streams with just the right amounts of oxygen and sulfide”, he said. “And that’s what's so nice about studying these environments. We can make these observations in the exact geochemical conditions that these organisms need to thrive.”

And while the machinations of hot spring-dwelling wigglers may feel far removed from human life, they expand our knowledge of how humans came to thrive and how various lifeforms adapt to their surroundings to ensure their survival, Dlakic said.

“It may seem counterintuitive to understand complex life by studying something that's simple, but that's really how it has to start,” he said. “You have to think back to understand where we are today.”

-end-

This story is available on the Web at: http://www.montana.edu/news/24277

END

Montana State scientists publish new research on ancient life found in Yellowstone hot springs

2025-02-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Generative AI bias poses risk to democratic values

2025-02-04

Generative AI, a technology that is developing at breakneck speed, may carry hidden risks that could erode public trust and democratic values, according to a study led by the University of East Anglia (UEA).

In collaboration with researchers from the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV) and Insper, both in Brazil, the research showed that ChatGPT exhibits biases in both text and image outputs — leaning toward left-wing political values — raising questions about fairness and accountability in its design.

The study revealed ...

Study examines how African farmers are adapting to mountain climate change

2025-02-03

A new international study highlights the severity of climate change impacts across African mountains, how farmers are adapting, and the barriers they face – findings relevant to people living in mountain regions around the world.

"Mountains are the sentinels of climate change,” said Julia Klein, a Colorado State University professor of ecosystem science and sustainability and co-author of the study. “Like the Arctic, some of the first extreme changes we're seeing are happening in mountains, from glaciers melting to extreme events. There's greater warming at higher elevations, so what's happening in mountains is foreshadowing what's going ...

Exposure to air pollution associated with more hospital admissions for lower respiratory infections

2025-02-03

Air pollution is a well-known risk factor for respiratory diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, its contribution to lower respiratory infections —those that affect the lower respiratory tract, including the lungs, bronchi and alveoli— is less well documented, especially in adults. To fill this gap in knowledge, a team from the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), a centre supported by the ”la Caixa” Foundation, assessed the effect of air pollution ...

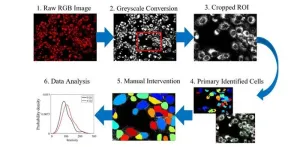

Microscopy approach offers new way to study cancer therapeutics at single-cell level

2025-02-03

Understanding how tumors change their metabolism to resist treatments is a growing focus in cancer research. As cancer cells adapt to therapies, their metabolism often shifts, which can help them survive and thrive despite medical interventions. This process, known as metabolic reprogramming, is a key factor in the development of treatment resistance. However, current methods to study these changes can be costly, complex, and often destructive to the cells being studied. Researchers at the University of Kentucky have developed a new, simpler approach to observe these metabolic shifts in cancer cells, offering a more accessible and effective tool for cancer research.

As ...

How flooding soybeans in early reproductive stages impacts yield, seed composition

2025-02-03

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — With an increasing frequency and intensity of flooding events and an eye to capitalize on a common rice production technique, soybean breeders are on a quest to develop varieties with flood tolerance at any stage in the plant’s development.

Farmers who use zero-grade fields for rice as their main production system are also interested in flood-tolerant soybean varieties for crop rotation, said Caio Vieira, assistant professor of soybean breeding and a researcher for the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, the University of Arkansas ...

Gene therapy may be “one shot stop” for rare bone disease

2025-02-03

For the last 10 years, the only effective treatment for hypophosphatasia (HPP) has been an enzyme replacement therapy that must be delivered by injection three-to-six times each week.

“It's been a tremendous success and has proven to be a lifesaving treatment,” said José Luis Millán, PhD, professor in the Human Genetics Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys. “Many children who have been treated otherwise would have died shortly after birth, and they are now able to look forward to long lives.

“It is, however, a very invasive treatment. Some patients have reactions from frequent injections and discontinue ...

Protection for small-scale producers and the environment?

2025-02-03

Sustainability certificates such as Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance and Cocoa Life promise to improve the livelihoods of small-scale cocoa producers while preserving the biodiversity on their plantations. Together with the European Commission's Joint Research Centre, researchers from the University of Göttingen have investigated whether sustainability certificates actually achieve both these goals. To find out, they carried out an analysis within the Ghanaian cocoa production sector. Their results show that although certification improves both cocoa yield and cocoa income for small-scale producers, they were unable to ...

Researchers solve a fluid mechanics mystery

2025-02-03

What began as a demonstration of the complexity of fluid systems became an art piece in the American Physical Society’s Gallery of Fluid Motion, and ultimately its own puzzle that the researchers just solved. Their new study is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

“We came up with this experiment because we were having a hard time convincing people of certain effects happening for the problem of drag reduction,” said assistant

professor Paolo Luzzatto-Fegiz, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering, whose research specialties include modeling flow and investigating drag — as ...

New grant funds first-of-its-kind gene therapy to treat aggressive brain cancer

2025-02-03

The California Institute for Regenerative Medicine has awarded a $6 million grant to USC investigators pioneering a new first-of-its-kind genetic therapy for glioblastoma, a severe form of brain cancer. The treatment would be the first gene therapy for glioblastoma to use a novel, more precise delivery system that is less likely to harm non-cancerous cells.

Glioblastoma is an aggressive and fast-growing cancer originating in the brain that occurs primarily in adults and has no known cure. Patients diagnosed with this type of tumor have a five-year survival rate of just 5 percent. The cancer’s location—in the sensitive brain—combined ...

HHS external communications pause prevents critical updates on current public health threats

2025-02-03

The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) is concerned that two weeks have passed since the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced a pause on mass communications and public appearances that are not directly related to emergencies or critical to preserving health. With the order remaining in effect until a new HHS secretary is confirmed, this unpredictable timeline prolongs uncertainty for both healthcare professionals and the public, and endangers the nation by hindering our ability to detect and respond to public health threats, such as avian influenza (H5N1). Public ...