(Press-News.org) Painted lady butterflies are world travelers. The ones we encounter in Europe fly from Africa to Sweden, ultimately returning to areas north and south of the Sahara. But what determines whether some butterflies travel long distances while others travel short distances? A group of scientists, including from the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), shows that the different migration strategies are shaped by environmental conditions rather than being encoded in the butterfly’s DNA.

It is a warm summer day in June. A group of scientists with sunhats and nets is hiking along a trail in the Catalan mountains. They meticulously search for painted ladies—vibrant orange butterflies with an intricate black-and-white pattern. Capturing painted ladies is not an easy task; they are strong, determined flyers, a fact that evolutionary biologist Daria Shipilina also had to acknowledge.

Previously working with plants and birds, the scientist tries to catch one of the beautiful butterflies in the air. Her net sways in all directions, but not where it needs to go. Finally, a few butterflies are taking a nectar break, giving Shipilina a long-awaited chance. A swift “swoosh”, and she nets one. A great moment for the biologist and an even greater testament to the resilience and endurance of these incredible butterflies.

Each year, painted ladies embark on a huge migratory journey from the northwest of Africa all the way up to Sweden and back to find the perfect environmental conditions that ensure their survival and reproduction.

A group of scientists, alongside citizen science projects, has been trying to decode the butterfly travel map. A recent interdisciplinary publication provides new insights. It features contributions from Shipilina—formerly at the University of Uppsala and currently a postdoc with Nicholas Barton's group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA)—along with collaborators from several institutions: the University of Ottawa, the CSIC-CMCNB in Barcelona, SOS Savane, the Polytechnic Higher School of Dakar, and the Technical University of Darmstadt. The results are now published in PNAS Nexus.

No distance too far, no burden too heavy

“The painted lady is a strikingly beautiful and colorful butterfly species,“ says Shipilina. “Watching them form large aggregations is a true spectacle. But what makes them particularly special is their incredible long-distance migrations.”

These butterflies go on a yearly 10,000 km journey between Africa and Europe. They do so through a succession of generations, looking for the best breeding conditions for their offspring. “Each individual travels in one section of the annual migratory cycle, with its offspring continuing their journey,” Shipilina continues.

The colorful insects begin their grand voyage in spring, starting from Northwest Africa and flying over the Mediterranean Sea to Europe. Subsequent generations then make their way to Great Britain, even reaching the Arctic tundra of Sweden to spend the summer.

Until recently, it was believed that once the butterflies reach Sweden, they perish due to the colder climates that arise there at the end of summer. However, studies have shown that painted ladies return to warmer regions in autumn, confirming a circular migratory pattern. While some end up staying in the Mediterranean area, others travel back to Africa, even crossing the Sahara. But how come? Do they have a different GPS systems?

Where have you been, where are you headed?

Shipilina and colleagues set out to understand this phenomenon. To achieve this, the scientists went on field trips and collected painted ladies from regions both north and south of the Sahara, including Benin, Senegal, Morocco, Spain, Portugal, and Malta.

They utilized isotope geolocation to estimate the geographic origin of each butterfly. “The key principle of this method is that the isotopic makeup—or the stable isotopes—of the adult butterfly’s wings mirrors the isotopic signature of the plants they ate as a caterpillar,” explains Shipilina. Isotopes are different forms of the same element, with identical chemical properties but slightly different atomic masses.

Co-first author Megan Reich and Clement Bataille from the University of Ottawa spent several years developing this technique, testing different isotopes, refining statistical approaches, and incorporating machine-learning techniques to enhance accuracy and resolution.

The analysis confirmed the diverse travel behavior among individuals: some took a long migration trip south from Scandinavia, crossing the Sahara, while others migrated a short distance, staying north of the desert in the Mediterranean region.

Is it in their genes?

The scientists then used whole genome sequencing to compare DNA sequences of each individual. Interestingly, there was no genetic difference between short-trip and long-trip butterflies.

“This finding fundamentally differs from what is observed in some birds, another well-studied migratory group,” Shipilina says. “For example, in willow warblers, a large chromosomal region has been associated with variable migratory direction, illustrating how different phenotypes arise from distinct genomic compositions.” Additionally, migration patterns in painted ladies could not be associated with factors such as sex, wing size, or wing shape.

Painted ladies adapt to the environment

According to the scientists, so-called phenotypic plasticity might explain the different migration styles. “Phenotypic plasticity is the ability of an organism to change its phenotype—in this case, its engagement in long- or short-distance migration—in response to environmental conditions without altering its genetic makeup,” explains Shipilina.

For instance, in summer, butterflies in Sweden might be prompted to migrate a long distance south across the Sahara due to the quick shift in day lengths or other seasonal cues. In contrast, butterflies in Southern France, where the days are longer, may not encounter those migratory cues and therefore only undertake short-distance journeys, staying in the Mediterranean area.

Compared to the other butterflies, like the well-studied monarch, much remains unknown about the migration of painted ladies. Does the observed pattern apply to the broad geographic distribution of the painted lady? Is this phenomenon unique to butterflies, or could it be observed in other insects as well? ISTA researcher Daria Shipilina and her colleagues are determined to close this knowledge gap—one paper at a time.

-

Information on animal studies

In order to better understand fundamental processes, for example, in the fields of neuroscience, immunology, or genetics, the use of animals in research is indispensable. No other methods, such as in silico models, can serve as alternative. The animals are raised, kept, and treated according to the strict regulations of the respective countries, the research was conducted.

END

Globetrotting not in the genes

New insights into the painted lady butterfly’s annual migration

2025-02-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Patient advocates from NCCN guidelines panels share their ‘united by unique’ stories for world cancer day

2025-02-04

PLYMOUTH MEETING, PA [February 4, 2025] — The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) is joining people and organizations across the globe to commemorate World Cancer Day today. World Cancer Day is a global initiative to improve awareness and knowledge of cancer risks and actions for better prevention, detection, and treatment. It is led and organized by the Union of International Cancer Control (UICC) every February 4.

World Cancer Day 2025 marks the start of the ‘United by Unique’ campaign to highlight how every experience with cancer is unique, even as people touched by cancer ...

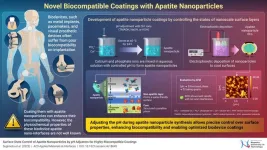

Innovative apatite nanoparticles for advancing the biocompatibility of implanted biodevices

2025-02-04

Medical implants have transformed healthcare, offering innovative solutions with advanced materials and technologies. However, many biomedical devices face challenges like insufficient cell adhesion, leading to inflammatory responses after their implantation in the body. Apatite coatings, particularly hydroxyapatite (HA)—a naturally occurring form of apatite found in bones, have been shown to promote better integration with surrounding tissues. However, the biocompatibility of artificially synthesized apatite nanoparticles often falls short of expectations, primarily due to the nanoparticles’ limited ability to bind effectively with biological tissues.

To overcome ...

Study debunks nuclear test misinformation following 2024 Iran earthquake

2025-02-04

A new study debunks claims that a magnitude 4.5 earthquake in Iran was a covert nuclear weapons test, as widely alleged on social media and some mainstream news outlets in October 2024, a period of heightened geopolitical tensions in the Middle East.

Led by Johns Hopkins University scientists, the study warns about the potential consequences of mishandling and misinterpreting scientific information, particularly during periods of international conflict. The findings appear in the journal Seismica.

“There was a concerted misinformation and disinformation campaign around this event that promoted the idea this was a nuclear test, ...

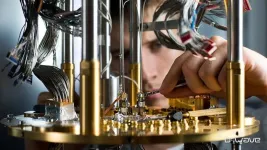

Quantum machine offers peek into “dance” of cosmic bubbles

2025-02-04

Physicists have performed a groundbreaking simulation they say sheds new light on an elusive phenomenon that could determine the ultimate fate of the Universe.

Pioneering research in quantum field theory around 50 years ago proposed that the universe may be trapped in a false vacuum – meaning it appears stable but in fact could be on the verge of transitioning to an even more stable, true vacuum state. While this process could trigger a catastrophic change in the Universe's structure, experts agree that predicting the timeline ...

How hungry fat cells could someday starve cancer to death

2025-02-04

How Hungry Fat Cells Could Someday Starve Cancer to Death

Scientists transformed energy-storing white fat cells into calorie-burning ‘beige’ fat. Once implanted, they outcompeted tumors for resources, beating back five different types of cancer in lab experiments.

Liposuction and plastic surgery aren’t often mentioned in the same breath as cancer.

But they are the inspiration for a new approach to treating cancer that uses engineered fat cells to deprive tumors of nutrition.

Researchers at UC San Francisco used the gene editing technology CRISPR to turn ordinary white fat cells into “beige” fat cells, which voraciously consume calories to make ...

Breakthrough in childhood brain cancer research could heal treatment-resistant tumors, keep them in remission

2025-02-04

Brain cancer is the second-leading cause of death in children in the developed world. For the children who survive, standard treatments have long-term impacts on their development and quality of life, particularly in small children and infants.

Research out of Emory University and QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Queensland, Australia, has shown that a potential new targeted therapy for childhood brain cancer is effective in infiltrating and killing tumor cells in preclinical models tested in mice.

In ...

Research discovery halts childhood brain tumor before it forms

2025-02-04

Scientists at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) have discovered a way to stop tumour growth before it starts for a subtype of medulloblastoma, the most common childhood malignant brain cancer.

Brain cancer presents a unique set of challenges for researchers – by the time a person experiences symptoms, the tumours are often so complex that the fundamental mechanisms driving the tumour growth are no longer easy to identify. A research team led by Dr. Peter Dirks is working to combat ...

Scientists want to throw a wrench in the gears of cancer’s growth

2025-02-04

Preventing the cell’s protein factories from making the notorious cancer-causing protein MYC could stop out-of-control tumors.

For decades, scientists have tried to stop cancer by disabling the mutated proteins that are found in tumors. But many cancers manage to overcome this and continue growing.

Now, UCSF scientists think they can throw a wrench into the fabrication of a key growth-related protein, MYC, that escalates wildly in 70% of all cancers. Unlike some other targets of cancer therapies, MYC can be dangerous simply due to its abundance.

In a paper that appears Feb. 4 in Nature Cell Biology, researchers at UC San Francisco ...

WSU researcher pioneers new study model with clues to anti-aging

2025-02-04

SPOKANE, Wash. — Washington State University scientists have created genetically-engineered mice that could help accelerate anti-aging research.

Globally, scientists are working to unlock the secrets of extending human lifespan at the cellular level, where aging occurs gradually due to the shortening of telomeres–the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes that function like shoelace tips to prevent unraveling. As telomeres shorten over time, cells lose their ability to divide for healthy ...

EU awards €5 grant to 18 international researchers in critical raw materials, the “21st century's gold”

2025-02-04

The new EU-funded consortium “ForMovFluid” will study how fluids transformed the materials inside the Earth's crust. Thanks to the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action Doctoral Networks programme, ForMovFluid will fund the doctoral studies of 18 researchers, and train them to become elite experts in the field of geoscience.

Moreover, this project will allow us to understand the origin of the so-called critical raw materials, of vital importance for the energy transition. Over a period of four years, ForMovFluid “Marie Curie” researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Globetrotting not in the genesNew insights into the painted lady butterfly’s annual migration