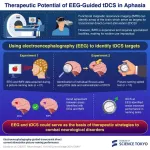

Electroencephalography may help guide treatments for language disorders

Researchers work towards an inexpensive and portable solution for treating aphasia

2025-02-06

(Press-News.org) Electroencephalography (EEG) may offer a more accessible alternative to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) for guiding transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) when treating aphasia. Researchers from Institute of Science Tokyo found an 80% agreement between EEG and fMRI in identifying brain regions activated during language tasks. Furthermore, EEG-guided tDCS improved picture-naming speed in participants, indicating its potential for innovative therapies in language disorders.

Many neurological disorders are directly linked to damage or deterioration in specific regions of the brain. For example, aphasia—a disorder characterized by impaired language abilities—is often caused by problems in Broca’s area, which is a region of the brain concerned with the production of speech. Although available therapies for aphasia are quite limited, scientists have been reporting functional improvements in patients by using transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS).

Briefly put, tDCS involves the application of a low electrical current to the scalp to modulate neuronal activity, aiming to enhance or suppress specific brain functions. Today, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is the most powerful tool available to pinpoint functional areas in the patient’s brain. However, fMRI requires large, expensive facilities and dedicated specialists, rendering this approach impractical for routine clinical applications. But what if there was a more accessible way of identifying specific functional regions of the brain, like Broca’s area?

In a recent study, which was published online in NeuroImage on January 6, 2025, a research team led by Professor Natsue Yoshimura of Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo), Japan, explored the potential of electroencephalography (EEG) as a tool to guide tDCS. “EEG measures the activity of neurons as electrical potentials on the scalp. It has the advantages of being relatively inexpensive and portable. If its disadvantage of low spatial resolution is overcome, EEG may thus offer a promising alternative to fMRI for determining sites for tDCS,” explains Yoshimura.

To test this hypothesis, the research team conducted two separate experiments. In the first one, they acquired EEG and fMRI data from 21 healthy participants as they completed picture-naming tasks. In these tasks, participants had to say the name of the object shown in a photograph as quickly as possible. The researchers then compared the activated areas of the brain identified based on either EEG or fMRI measurements. Interestingly, they found a remarkable 80% agreement between both methods, supporting the hypothesis.

In the second experiment, the researchers investigated whether tDCS applied to functional areas identified via EEG could improve performance in picture-naming tasks among 15 healthy participants. Compared to the standard approach, in which tDCS is applied directly to Broca’s area as determined by considering the conventional geometrical position, EEG-guided tDCS led to a marked improvement in picture-naming speed.

Together, these findings not only confirm the team’s hypothesis but also underscore the significant potential of EEG in improving language functions, which may contribute to the enhancement of the rehabilitation process for aphasia. “Our study provides the first indication that EEG-guided tDCS, considering the significant individual differences in brain activity, has the potential to be more effective in improving language function than conventional tDCS methods targeting Broca’s area in people with aphasia. The results also suggest EEG-based analysis may be effective for identifying brain areas relevant to specific cognitive tasks,” concludes Yoshimura.

Continued advancements in this field will hopefully lead to effective therapeutic strategies for people affected by aphasia.

About Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo)

Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo) was established on October 1, 2024, following the merger between Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) and Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech), with the mission of “Advancing science and human wellbeing to create value for and with society.”

END

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2025-02-06

Measurements and data collected from space can be used to better understand life on Earth.

An ambitious, multinational research project funded by NASA and co-led by UC Merced civil and environmental engineering Professor Erin Hestir demonstrated that Earth’s biodiversity can be monitored and measured from space, leading to a better understanding of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Hestir led the team alongside University of Buffalo geography Professor Adam Wilson and Professor Jasper Slingsby from the University ...

2025-02-06

Embargoed for release: Thursday, February 6, 2025, 2:00 PM ET

Key points:

Comprehensive genetic mapping of Plasmodium knowlesi, a zoonotic parasite that causes malaria, has revealed the genes required for malaria infection of the blood, and those driving drug resistance.

By identifying specific druggable targets and determinants of resistance, the map provides insights that could help the development of new therapeutics.

Boston, MA—A new, comprehensive map of all the genes essential for blood infections in Plasmodium knowlesi (P. ...

2025-02-06

In brief:

• In Greenland, an international team of researchers led by ETH Zurich has discovered that countless tiny ice quakes take place deep inside ice streams.

• These quakes are responsible for the fact that ice streams also move with a continuous stick-slip motion and not only like viscous honey as previously considered.

• The researchers recorded seismic data from inside the ice stream using a fibre-optic cable in a 2,700-metre deep borehole.

The ...

2025-02-06

Whale song can be as efficient as – and, in some cases, more efficient than – human communication, according to a new study in Science Advances. Meanwhile, new unrelated research in Science further investigates whale song’s adherence to a universal linguistic law, as observed in recordings of humpback whales.

Natural selection favors the pithy over the longwinded. For example, yelling “Duck!” is faster and far more effective than shouting “Be careful, there is an incoming projectile, and you need to move out of the way!” ...

2025-02-06

Researchers have uncovered a neural mechanism in the brains of mice that enables them to override instinctive fear responses; dysfunction in this mechanism may contribute to inappropriate or excessive fear responses, they say. According to the findings, targeting these circuits could offer new therapeutic avenues for treating fear-related disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety. Fear responses to visual threats, such as escaping from an approaching predator, are critical instinctive reactions for survival and are ...

2025-02-06

The hormone adrenomedullin disrupts insulin signaling in blood vessel cells, contributing to systemic insulin resistance in obesity-associated type 2 diabetes, according to a new study. Blocking adrenomedullin’s effects restores insulin function and improves glucose control in a mouse model, suggesting a potential new target for treating obesity-related metabolic disease. Diabetes is a leading global cause of illness, mortality, and healthcare expenditures, with most cases stemming from obesity-induced insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Insulin resistance primarily ...

2025-02-06

In this Special Issue of Science, 3 Reviews and a Policy Forum highlight research on Earth’s frozen places – from the Arctic to the Antarctic – and how it’s changing due to climate change and the geopolitical challenges this important work faces. In the first Review, Julienne Stroeve and colleagues provide a preview of what the Arctic region may look like in a warmer world. Without stronger climate action, global temperatures are set to rise +2.7°C above preindustrial levels, ...

2025-02-06

Researchers at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre (SWC) at UCL have unveiled the precise brain mechanisms that enable animals to overcome instinctive fears. Published today in Science, the study in mice could have implications for developing therapeutics for fear-related disorders such as phobias, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The research team, led by Dr Sara Mederos and Professor Sonja Hofer, mapped out how the brain learns to suppress responses to perceived threats that prove ...

2025-02-06

Known for their powerful punch, mantis shrimp can smash a shell with the force of a .22 caliber bullet. Yet, amazingly, these tough critters remain intact despite the intense shockwaves created by their own strikes.

Northwestern University researchers have discovered how mantis shrimp remain impervious to their own punches. Their fists, or dactyl clubs, are covered in layered patterns, which selectively filter out sound. By blocking specific vibrations, the patterns act like a shield against self-generated shockwaves.

The study will be published on Friday (Feb. 7) in the journal Science.

The findings someday could be applied to developing ...

2025-02-06

A corn plant knows how to find water in soil with the very tips of its roots, but some varieties, including many used for breeding high-yielding corn in the U.S., appear to have lost a portion of that ability, according to a Stanford-led study. With climate change increasing droughts, the findings hold potential for developing more resilient varieties of corn.

The study, published in the journal Science, uncovers genetic mechanisms behind root “hydropatterning,” or how plant roots branch toward water and avoid dry spaces in soil. In particular, the researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Electroencephalography may help guide treatments for language disorders

Researchers work towards an inexpensive and portable solution for treating aphasia