(Press-News.org) For the first time, scientists have demonstrated that negative refraction can be achieved using atomic arrays - without the need for artificially manufactured metamaterials.

Scientists have long sought to control light in ways that appear to defy the laws of Nature.

Negative refraction - a phenomenon where light bends in the opposite direction to its usual behaviour - has captivated researchers for its potential to revolutionise optics, enabling transformative technologies such as superlenses and cloaking devices.

Now, carefully arranged arrays of atoms have brought these possibilities a step closer, achieving negative refraction without the need for artificially manufactured metamaterials.

In research published in Nature Communications, Lancaster University Physics Professor Janne Ruostekoski and Dr Kyle Ballantine, with Dr Lewis Ruks from NTT Basic Research Laboratories in Japan, demonstrated a novel way of controlling interactions between atoms and light.

Natural materials interact with light through atomic transitions, where electrons jump between different energy levels. However, this interaction process has significant limitations. For instance, light primarily interacts with its electric field component, leaving the magnetic field component largely unused.

These inherent constraints in the optical properties of natural materials have driven the development of artificially engineered metamaterials which rely on the phenomenon of negative refraction.

Refraction occurs when light changes direction as it passes, e.g., from air into water or glass. Negative refraction, however, is a counterintuitive effect where light in a medium bends in the opposite direction to what is typically observed in nature, challenging conventional understanding of how light behaves in materials.

The allure of negative refraction lies in its groundbreaking potential applications, such as creating a perfect lens capable of focusing and imaging beyond the diffraction limit or developing cloaking devices that render objects invisible.

While negative refraction has been achieved in metamaterials, practical applications at optical frequencies remain hampered by fabrication imperfections and non-radiative losses, which still severely limit applications.

The novel approach by the Lancaster and NTT team involves performing detailed, atom-by-atom simulations of light propagating through atomic arrays.

Their work demonstrates that the cooperative response of atoms can enable negative refraction, eliminating the need for metamaterials altogether.

Professor Janne Ruostekoski from Lancaster University said: “In such cases, atoms interact with one another via the light field, responding collectively rather than independently. This means the response of a single atom no longer provides a simple guide to the behaviour of the entire ensemble. Instead, the collective interactions give rise to emergent optical properties, such as negative refraction, which cannot be predicted by examining individual atoms in isolation.”

These effects are made possible by trapping atoms in periodic optical lattices. Optical lattices are like "egg cartons" made of light, where atoms are held in place by standing light waves.

Dr Lewis Ruks at NTT said: “These precisely arranged atomic crystals allow researchers to control the interactions between atoms and light with extraordinary precision, paving the way for novel technologies based on negative refraction.”

The collective behaviour of atoms in optical lattices offers several key advantages. Unlike artificially manufactured metamaterials, atomic systems provide a pristine, clean medium free from fabrication imperfections. In such systems, light interacts with atoms in a controlled and precise manner, without the absorption losses that typically convert light into heat.

These unique properties make atomic media a promising alternative to metamaterials for practical applications of negative refraction.

END

Negative refraction of light using atoms instead of metamaterials

2025-02-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

High BP may develop at different ages and paces in East & South Asian adults in the UK

2025-02-12

Research Highlights:

A data analysis projected that South Asian adults living in the United Kingdom may experience elevated blood pressure nine years earlier than East Asian adults on average.

The largest blood pressure disparities between South Asian and East Asian adults were projected to be in 18-39-year-old men and 40–64-year-old women.

The projected increase in systolic blood pressure in middle age East Asian adults was linked to a nearly 2.5 times higher risk for heart disease caused by blocked arteries and a nearly fourfold greater risk of stroke. Even at an older age, high systolic ...

Meet the newly discovered brain cell that allows you to remember objects

2025-02-12

Take a look around your home and you’ll find yourself surrounded by familiar comforts—photos of family and friends on the wall, well-worn sneakers by the door, a shelf adorned with travel mementos.

Objects like these are etched into our memory, shaping who we are and helping us navigate environments and daily life with ease. But how do these memories form? And what if we could stop them from slipping away under a devastating condition like Alzheimer’s disease?

Scientists at UBC’s faculty of medicine have ...

Engineered animals show new way to fight mercury pollution

2025-02-12

Australian scientists have found an effective new way to clean up methylmercury, one of the world’s most dangerous pollutants, which often builds up in our food and environment because of industrial activities such as illegal gold mining and burning coal. The discovery, published in Nature Communications on 12 February 2025, could lead to new ways of engineering animals to protect both wildlife and human health.

The research team from Macquarie University's Applied BioSciences, CSIRO, Macquarie Medical School, and the ARC Centre of Excellence in Synthetic Biology, has successfully genetically modified fruit flies and zebrafish to transform methylmercury into a ...

The 3,000-year coral reef shutdown: a mysterious pause and a remarkable recovery

2025-02-12

New study reveals that coral reefs in the Gulf of Eilat experienced a surprising 3,000-year "shutdown" in growth, from about 4,400 to 1,000 years ago, likely due to a temporary drop in sea level that could have been caused by global cooling. This phenomenon, which aligns with similar reef interruptions in Mexico, Brazil, and Australia, suggests a widespread environmental shift during that period. Despite the long pause, the reef eventually recovered, with coral species reappearing from deeper ...

Worm surface chemistry reveals secrets to their development and survival

2025-02-12

A new study has revealed the clearest-ever picture of the surface chemistry of worm species that provides groundbreaking insights into how animals interact with their environment and each other. These discoveries could pave the way for strategies to deepen our understanding of evolutionary adaptations, refine behavioural research, and ultimately overcome parasitic infections.

Scientists from the University’s School of Pharmacy used an advanced mass spectrometry imaging system to examine the nematodes Caenorhabditis elegans and Pristionchus pacificus, aiming to characterise species-specific surface chemical ...

Splicing twins: unravelling the secrets of the minor spliceosome complex

2025-02-12

In human cells, only a small proportion of the information written in genes is used to produce proteins. How does the cell select this information? A large molecular machine called the spliceosome continuously separates the coding and non-coding regions of our genes – and it's doing this even as you read these lines.

The spliceosome is critical for the proper functioning of every cell, and numerous genetic disorders are linked to problems with spliceosome function. In most eukaryotic cells, two types of ...

500-year-old Transylvanian diaries show how the Little Ice Age completely changed life and death in the region

2025-02-12

Glaciers, sediments, and pollen can be used to reconstruct the climate of the past. Beyond ‘nature’s archive,’, other sources, such as diaries, travel notes, parish or monastery registers, and other written documents – known at the ‘society’s archive’ – contain reports and observations about local climates in bygone centuries.

In contrast, the second half of the century was characterized by heavy rainfall and floods, particularly in the 1590s.

The western parts of the European continent cooled significantly when in the 16th century a period known as the ‘Little Ice Age’ intensified. During the second ...

Overcoming nicotine withdrawal: Clues found in neural mechanisms of the brain

2025-02-12

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 22% of the global population smokes, with more than 9 million smoking-related deaths reported annually. Effective treatments to alleviate nicotine withdrawal symptoms caused by smoking cessation are essential for successful smoking cessation. Currently, approved treatments for nicotine withdrawal include Bupropion and Varenicline, but there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options to improve smoking cessation success rates.

The research team led by Dr. Heh-In Im at the Center for Brain Disorders of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) has identified a novel brain region and neural mechanism ...

Survey: Women prefer female doctors, but finding one for heart health can be difficult

2025-02-12

EMBARGOED UNTIL WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2025

Mountain View, CA (Feb. 12, 2025) – According to the U.S. Physician Workforce Data Dashboard, only about 17% of cardiologists are women, ranking as one of the lowest specialties among female physicians, yet heart disease remains the number one killer of women, accounting for one in five female deaths. El Camino Health is innovating a solution to address the unique symptoms and risk factors of heart disease in women.

A new national survey conducted by El Camino Health found women (59%) are ...

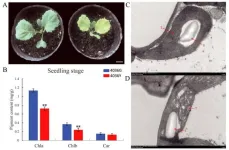

Leaf color mysteries unveiled: the role of BoYgl-2 in cabbage

2025-02-12

A new study has uncovered a novel P-type PPR protein, BoYgl-2, which plays a crucial role in chloroplast RNA editing and chlorophyll biosynthesis in cabbage. This discovery sheds new light on the molecular mechanisms governing leaf color formation and chloroplast development, filling a significant knowledge gap in plant physiology. By identifying a spontaneous yellow-green leaf mutant and deciphering the function of BoYgl-2, the research paves the way for innovative crop breeding strategies that could enhance plant productivity and agricultural sustainability.

Leaf color is more than just an aesthetic trait—it is a vital agronomic characteristic ...