(Press-News.org) In the past two years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved two novel Alzheimer’s therapies, based on data from clinical trials showing that both drugs slowed the progression of the disease. But while the approvals of lecanemab and donanemab, both antibody therapies that clear plaque-causing amyloid proteins from the brain, were greeted with enthusiasm by some Alzheimer’s researchers, the response of patients has been muted. According to physicians who care for people with Alzheimer’s, many patients found it difficult to understand what the clinical trials results — presented as “percent decrease in the rate of cognitive decline” — meant for their own lives.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have devised a way to communicate the effects of taking the new Alzheimer’s medications in language that is accessible and understandable to patients and their families. Using data on the natural history of the disease and the magnitude of the drugs’ effects as measured in clinical trials, the researchers calculated how many months of independent living an Alzheimer’s patient could expect to gain by undergoing treatment. The benefits depended on the drug and the severity of the patient’s symptoms at the time treatment began. As a representative example, a typical patient who started treatment with very mild symptoms could expect to live independently for an additional 10 months if treated with lecanemab, or eight months with donanemab.

The study, published Feb. 13 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, provides crucial information that can help patients and caregivers weigh the benefits against the costs and risks of treatment.

“What we were trying to do was figure out how to give people a piece of information that would be meaningful to them and help them make decisions about their care,” said senior author Sarah Hartz, MD, PhD, a professor of psychiatry at WashU Medicine. “What people want to know is how long they will be able to live independently, not something abstract like the percent change in decline.”

Alzheimer’s patients and their families are faced with the tough question of whether to undergo a treatment that will not make them better. It won’t even stop them from getting worse. At best, treatment with lecanemab or donanemab could slow the inevitable cognitive decline that characterizes Alzheimer’s. Add to this the facts that treatment is expensive, requires biweekly or monthly infusions, and carries risks such as brain bleeds and brain swelling that are usually mild and go away on their own but can, in rare cases, be life-threatening.

But just because the benefits are limited doesn’t mean they are not valuable to patients and their families.

“My patients want to know, ‘How long can I drive? How long will I be able to take care of my own personal hygiene? How much time would this treatment give me?’” said co-author Suzanne Schindler, MD, PhD, an associate professor of neurology and a WashU Medicine physician who treats people with Alzheimer’s disease. “The question of whether or not these drugs would be helpful for any particular person is complicated and has to do with not only medical factors, but the patient’s priorities, preferences and risk tolerance.”

Living independently with Alzheimer’s disease

There are two critical inflection points on the continuum between independence and dependency. The first is the point where a person can no longer live independently because of an impaired ability to manage everyday tasks such as preparing meals, driving, paying bills and remembering appointments. The second point comes when a person can no longer care for his or her own body, and requires assistance with bathing, dressing and toileting.

To calculate the effects of treatment, Hartz and her colleagues first estimated when people could expect to lose each of the two kinds of independence if left untreated. They analyzed the experiences of 282 people who participated in research studies at WashU Medicine’s Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center. All participants met the criteria for treatment with the two new drugs, but hadn’t received them previously. The researchers also calculated how quickly symptoms progressed without treatment.

Using these data on independence and progression, combined with the reported effects of the two drugs, the researchers calculated the amount of time a person at each stage of the disease could be expected to live or care for themselves independently without treatment, and how this progression would compare to those who received treatment.

A typical person with very mild symptoms could expect to live independently for another 29 months without treatment, 39 months with lecanemab, and 37 months with donanemab.

Most people with mild symptoms — as opposed to very mild symptoms — were already unable to live independently at baseline, so for them the more relevant measure was how much longer they would be able to care for themselves. The researchers calculated that a typical person at this stage of the disease could expect to manage self-care independently for an additional 26 months if treated with lecanemab, 19 months with donanemab.

This way of understanding the effects of the drugs could help patients and their families make decisions about their care, the authors said.

“The purpose of this study is not to advocate for or against these medications,” Hartz said. “The purpose of the paper is to put the impact of these medications into context in ways that can help people make the decisions that are best for themselves and their family members.”

Hartz SM, Schindler SE, Streitz ML, Moulder KL, Mozersky J, Wang G, Xiong C, Morris JC. Assessing the clinical meaningfulness of slowing CDR-SB progression with disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. Feb. 13, 2025. DOI: 10.1002/trc2.70033

This study is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers P30 AG066444, P01 AG003991, P01 AG026276, R01 AG065234, R01 AA029308, R01 AG067505, R01 AG070941, U01 AA008401 and UL1 TR002345. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

About Washington University School of Medicine

WashU Medicine is a global leader in academic medicine, including biomedical research, patient care and educational programs with 2,900 faculty. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio is the second largest among U.S. medical schools and has grown 56% in the last seven years. Together with institutional investment, WashU Medicine commits well over $1 billion annually to basic and clinical research innovation and training. Its faculty practice is consistently within the top five in the country, with more than 1,900 faculty physicians practicing at 130 locations and who are also the medical staffs of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals of BJC HealthCare. WashU Medicine has a storied history in MD/PhD training, recently dedicated $100 million to scholarships and curriculum renewal for its medical students, and is home to top-notch training programs in every medical subspecialty as well as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communications sciences.

END

Next-gen Alzheimer’s drugs extend independent living by months

New analysis recasts benefits of treatment in relation to day-to-day impacts on patients’ lives

2025-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Jumping workouts could help astronauts on the moon and Mars, study in mice suggests

2025-02-13

Jumping workouts could help astronauts prevent the type of cartilage damage they are likely to endure during lengthy missions to Mars and the Moon, a new Johns Hopkins University study suggests.

The research adds to ongoing efforts by space agencies to protect astronauts against deconditioning/getting out of shape due to low gravity, a crucial aspect of their ability to perform spacewalks, handle equipment and repairs, and carry out other physically demanding tasks.

The study, which shows knee cartilage in mice grew healthier following jumping exercises, appears ...

Guardian molecule keeps cells on track – new perspectives for the treatment of liver cancer

2025-02-13

A guardian molecule ensures that liver cells do not lose their identity. This has been discovered by researchers from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), the Hector Institute für Translational Brain Research (HITBR), and from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL). The discovery is of great interest for cancer medicine because a change of identity of cells has come into focus as a fundamental principle of carcinogenesis for several years. The Heidelberg researchers were able to show ...

Solar-powered device captures carbon dioxide from air to make sustainable fuel

2025-02-13

Researchers have developed a reactor that pulls carbon dioxide directly from the air and converts it into sustainable fuel, using sunlight as the power source.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, say their solar-powered reactor could be used to make fuel to power cars and planes, or the many chemicals and pharmaceuticals products we rely on. It could also be used to generate fuel in remote or off-grid locations.

Unlike most carbon capture technologies, the reactor developed by the Cambridge researchers does not require fossil-fuel-based power, or the transport and storage of carbon dioxide, but instead converts atmospheric CO2 into something useful using sunlight. ...

Bacteria evolved to help neighboring cells after death, new research reveals

2025-02-13

Darwin’s theory of natural selection provides an explanation for why organisms develop traits that help them survive and reproduce.

Because of this, death is often seen as a failure rather than a process shaped by evolution.

When organisms die, their molecules need to be broken down for reuse by other living things.

Such recycling of nutrients is necessary for new life to grow.

Now a study led by Professor Martin Cann of ...

Lack of discussion drives traditional gender roles in parenthood

2025-02-13

Conversations about parental duties continue to be led by mothers, even if both parents earn the same amount of money, finds a new study by a UCL researcher.

A new study by Dr Clare Stovell (IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education & Society), published in the Journal of Family Studies, highlights how a lack of discussion between parents about important choices such as parental leave, work and childcare is perpetuating traditional gender roles.

The study found that women usually lead the conversations and there is little discussion about the man’s work schedule, even in cases where the woman earns as much or more than her partner.

Dr Stovell said: “These interviews ...

Scientists discover mechanism driving molecular network formation

2025-02-13

Covalent bonding is a widely understood phenomenon that joins the atoms of a molecule by a shared electron pair. But in nature, patterns of molecules can also be connected through weaker, more dynamic forces that give rise to supramolecular networks. These can self-assemble from an initial molecular cluster, or crystal, and grow into large, stable architectures.

Supramolecular networks are essential for maintaining the structure and function of biological systems. For example, to ‘eat’, cells rely ...

Comprehensive global study shows pesticides are major contributor to biodiversity crisis

2025-02-13

Pesticides are causing overwhelming negative effects on hundreds of species of microbes, fungi, plants, insects, fish, birds and mammals that they are not intended to harm – and globally their use is a major contributor to the biodiversity crisis.

That is the finding of the first study assessing the impacts of pesticides across all types of species in land and water habitats, carried out by an international research team that included the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH) and the University of Sussex.

Multiple negative impacts

The scientists analysed over 1,700 existing lab and field studies of the impacts of 471 different ...

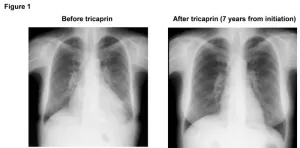

A simple supplement improves survival in patients with a new type of heart disease

2025-02-13

Osaka, Japan – Heart transplant is a scary and serious surgery with high cost, but for patients with heart failure it can be the only option for cure. Now, however, a multi-institutional research team led by Osaka University has found that simply taking a supplement might be all that is needed for certain patients with heart failure to recover – no surgery needed.

In a study published in Nature Cardiovascular Research, the research team found that tricaprin, a natural supplement, can improve long-term survival and recovery from heart failure in patients with triglyceride deposit cardiomyovasculopathy ...

Uncovering novel transcriptional enhancers in neuronal development and neuropsychiatric disorders

2025-02-13

Neuropsychiatric disorders are becoming increasingly prevalent. Given their complex and multifactorial pathogenesis, there is an urgent need for effective and targeted therapies that can improve patients’ quality of life. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified various genetic alterations that contribute to the development and progression of neuropsychiatric disorders, ranging from mild dyslexia to more severe conditions such as schizophrenia.

While thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—changes in a single nucleotide position in the DNA—have been associated with neurological ...

IR Sant Pau study reveals immune system’s crucial role in ALS at cellular level

2025-02-13

A team of researchers from the Sant Pau Research Institute (IR Sant Pau) has published a study in the Journal of Neuroinflammation that, for the first time, examines in depth the role of the peripheral immune system in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) at the single-cell level. Their findings suggest that immune system cells—particularly two subpopulations of Natural Killer (NK) cells—may play a crucial part in the development and progression of this neurodegenerative disease.

ALS is a condition that causes the progressive degeneration of motor neurones, leading to a loss of muscle function and, eventually, affecting ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Yale study challenges notion that aging means decline, finds many older adults improve over time

Korean researchers enable early detection of brain disorders with a single drop of saliva!

Swipe right, but safer

Duke-NUS scientists identify more effective way to detect poultry viruses in live markets

Low-intensity treadmill exercise preconditioning mitigates post-stroke injury in mouse models

How moss helped solve a grave-robbing mystery

How much sleep do teens get? Six-seven hours.

Patients regain weight rapidly after stopping weight loss drugs – but still keep off a quarter of weight lost

GLP-1 diabetes drugs linked to reduced risk of addiction and substance-related death

Councils face industry legal threats for campaigns warning against wood burning stoves

GLP-1 medications get at the heart of addiction: study

Global trauma study highlights shared learning as interest in whole blood resurges

Almost a third of Gen Z men agree a wife should obey her husband

Trapping light on thermal photodetectors shatters speed records

New review highlights the future of tubular solid oxide fuel cells for clean energy systems

Pig farm ammonia pollution may indirectly accelerate climate warming, new study finds

Modified biochar helps compost retain nitrogen and build richer soil organic matter

First gene regulation clinical trials for epilepsy show promising results

Life-changing drug identified for children with rare epilepsy

Husker researchers collaborate to explore fear of spiders

Mayo Clinic researchers discover hidden brain map that may improve epilepsy care

NYCST announces Round 2 Awards for space technology projects

How the Dobbs decision and abortion restrictions changed where medical students apply to residency programs

Microwave frying can help lower oil content for healthier French fries

In MS, wearable sensors may help identify people at risk of worsening disability

Study: Football associated with nearly one in five brain injuries in youth sports

Machine-learning immune-system analysis study may hold clues to personalized medicine

A promising potential therapeutic strategy for Rett syndrome

How time changes impact public sentiment in the U.S.

Analysis of charred food in pot reveals that prehistoric Europeans had surprisingly complex cuisines

[Press-News.org] Next-gen Alzheimer’s drugs extend independent living by monthsNew analysis recasts benefits of treatment in relation to day-to-day impacts on patients’ lives