(Press-News.org) Broca’s aphasia is caused by damage to the frontal lobe, leaves patients unable to say what they intend to say

First study to identify regions outside the frontal lobe that encode the intent to speak

Critical for technology to avoid decoding a patient’s thoughts that are not intended to be spoken aloud

CHICAGO --- Imagine seeing a furry, four-legged animal that meows. Mentally, you know what it is, but the word “cat” is stuck on the tip of your tongue.

This phenomenon, known as Broca’s aphasia or expressive aphasia, is a language disorder that affects a person’s ability to speak or write. While the current go-to treatment is speech therapy, scientists at Northwestern University are working toward a different, possibly more effective treatment: using a brain computer interface (BCI) to convert brain signals into spoken words.

The first step in this process is determining where in the brain the BCI should record from to decode someone’s intended speech.

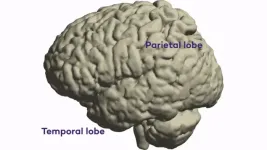

Currently, BCI devices are only used on individuals with paralysis from ALS or stroke in the brainstem, which leaves them unable to move or communicate. In these patients, BCIs record signals from the frontal lobe. But Broca’s aphasia, which most often affects people after a stroke or brain tumor, results from damage to the frontal lobe of the brain, where speech production and parts of language are processed. So, to help patients with Broca’s aphasia, scientists would likely need to record signals from other areas of the brain.

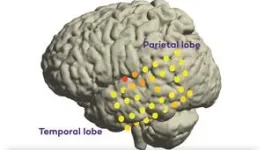

In a new study, Northwestern Medicine scientists have, for the first time, identified specific brain regions outside the frontal lobe — in the temporal and parietal cortices — involved in the intent to produce speech. This opens the door to one day using a BCI to treat Broca’s aphasia.

“This is a small, but necessary step,” said corresponding author Dr. Marc Slutzky, professor of neurology and neuroscience at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “We showed that these non-frontal areas indeed contain information about someone’s intent to produce speech that allowed us to distinguish when they were going to speak versus when they’re not speaking or are just thinking about something that they don’t want to say out loud.”

The study will be published Feb. 13 in the Journal of Neural Engineering.

These early findings will help scientists when they eventually design a BCI for patients with Broca’s aphasia to distinguish whether someone’s speech-related information is related to language production or language perception (including comprehension).

“It is critical to not be decoding the user’s thoughts that are not intended to be spoken aloud, both for that practical reason and for the ethical problems this could incur,” Slutzky said.

Study was in patients without a language deficit

While the goal is to one day work with patients with aphasia, this study was in patients who did not have language deficits.

The scientists recorded electrical signals from the surface of the cortex in nine patients (at Northwestern Memorial Hospital) with either epilepsy or brain tumors. The electrode arrays were either implanted in people with epilepsy as part of their seizure monitoring prior to surgery or placed on the brain temporarily in the operating room, while patients with tumors underwent awake brain surgery and mapping.

Then, patients either read words aloud from a monitor or were silent (at rest) while investigators recorded their brain signals (called electrocorticography or ECoG).

The next step in this research will be to decode what these patients actually said.

The study is titled, “Decoding speech intent from non-frontal cortical areas.” Other Northwestern authors include first author Prashanth Prakash; Tianhao Lei; Robert D. Flint; Jason K. Hsieh; Zachary Fitzgerald; Emily Mittag Mugler; Jessica Templer; Matthew A Goldrick; Matthew C Tate; Joshua M. Rosenow; and Joshua I. Glaser.

The research was funded by grants R01NS099210, R01NS112942, RF1NS125026, R21NS084069, F32DC015708 and R01NS094748 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; National Science Foundation grant #1321015; and Northwestern Memorial Foundation Dixon Translational Research Grant (supported in part by NIH grants UL1RR025741 and UL1TR000150).

END

In the past two years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved two novel Alzheimer’s therapies, based on data from clinical trials showing that both drugs slowed the progression of the disease. But while the approvals of lecanemab and donanemab, both antibody therapies that clear plaque-causing amyloid proteins from the brain, were greeted with enthusiasm by some Alzheimer’s researchers, the response of patients has been muted. According to physicians who care for people with Alzheimer’s, many patients found it difficult to understand what the clinical trials results — presented as “percent decrease in ...

Jumping workouts could help astronauts prevent the type of cartilage damage they are likely to endure during lengthy missions to Mars and the Moon, a new Johns Hopkins University study suggests.

The research adds to ongoing efforts by space agencies to protect astronauts against deconditioning/getting out of shape due to low gravity, a crucial aspect of their ability to perform spacewalks, handle equipment and repairs, and carry out other physically demanding tasks.

The study, which shows knee cartilage in mice grew healthier following jumping exercises, appears ...

A guardian molecule ensures that liver cells do not lose their identity. This has been discovered by researchers from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), the Hector Institute für Translational Brain Research (HITBR), and from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL). The discovery is of great interest for cancer medicine because a change of identity of cells has come into focus as a fundamental principle of carcinogenesis for several years. The Heidelberg researchers were able to show ...

Researchers have developed a reactor that pulls carbon dioxide directly from the air and converts it into sustainable fuel, using sunlight as the power source.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, say their solar-powered reactor could be used to make fuel to power cars and planes, or the many chemicals and pharmaceuticals products we rely on. It could also be used to generate fuel in remote or off-grid locations.

Unlike most carbon capture technologies, the reactor developed by the Cambridge researchers does not require fossil-fuel-based power, or the transport and storage of carbon dioxide, but instead converts atmospheric CO2 into something useful using sunlight. ...

Darwin’s theory of natural selection provides an explanation for why organisms develop traits that help them survive and reproduce.

Because of this, death is often seen as a failure rather than a process shaped by evolution.

When organisms die, their molecules need to be broken down for reuse by other living things.

Such recycling of nutrients is necessary for new life to grow.

Now a study led by Professor Martin Cann of ...

Conversations about parental duties continue to be led by mothers, even if both parents earn the same amount of money, finds a new study by a UCL researcher.

A new study by Dr Clare Stovell (IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education & Society), published in the Journal of Family Studies, highlights how a lack of discussion between parents about important choices such as parental leave, work and childcare is perpetuating traditional gender roles.

The study found that women usually lead the conversations and there is little discussion about the man’s work schedule, even in cases where the woman earns as much or more than her partner.

Dr Stovell said: “These interviews ...

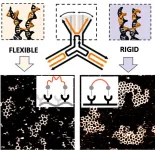

Covalent bonding is a widely understood phenomenon that joins the atoms of a molecule by a shared electron pair. But in nature, patterns of molecules can also be connected through weaker, more dynamic forces that give rise to supramolecular networks. These can self-assemble from an initial molecular cluster, or crystal, and grow into large, stable architectures.

Supramolecular networks are essential for maintaining the structure and function of biological systems. For example, to ‘eat’, cells rely ...

Pesticides are causing overwhelming negative effects on hundreds of species of microbes, fungi, plants, insects, fish, birds and mammals that they are not intended to harm – and globally their use is a major contributor to the biodiversity crisis.

That is the finding of the first study assessing the impacts of pesticides across all types of species in land and water habitats, carried out by an international research team that included the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH) and the University of Sussex.

Multiple negative impacts

The scientists analysed over 1,700 existing lab and field studies of the impacts of 471 different ...

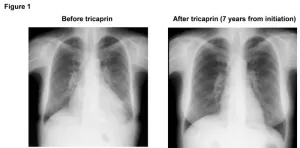

Osaka, Japan – Heart transplant is a scary and serious surgery with high cost, but for patients with heart failure it can be the only option for cure. Now, however, a multi-institutional research team led by Osaka University has found that simply taking a supplement might be all that is needed for certain patients with heart failure to recover – no surgery needed.

In a study published in Nature Cardiovascular Research, the research team found that tricaprin, a natural supplement, can improve long-term survival and recovery from heart failure in patients with triglyceride deposit cardiomyovasculopathy ...

Neuropsychiatric disorders are becoming increasingly prevalent. Given their complex and multifactorial pathogenesis, there is an urgent need for effective and targeted therapies that can improve patients’ quality of life. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified various genetic alterations that contribute to the development and progression of neuropsychiatric disorders, ranging from mild dyslexia to more severe conditions such as schizophrenia.

While thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—changes in a single nucleotide position in the DNA—have been associated with neurological ...