(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – How do you tell if someone has a particular accent? It might seem obvious: You hear someone pronounce words in a way that is different from “normal” and connect it to other people from a specific place.

But a new study suggests that might not be the case.

“People probably don’t learn who has an accent from hearing someone talk and thinking, ‘huh, they sound funny’ – even though sometimes it feels like that’s how we do it,” said Kathryn Campbell-Kibler, author of the study and associate professor of linguistics at The Ohio State University.

Accents may be more of something we learn culturally, Campbell-Kibler said.

The study was published online recently in the Journal of Sociolinguistics.

The study is part of a long-term project that Ohio State researchers have been conducting at the Language Sciences Research Lab at the Center of Science and Industry (COSI), a science museum in Columbus.

In this study, researchers asked visitors to the museum to participate in a study about accents. In the end, 1,106 people age 9 and up – mostly Ohioans – took part.

All participants heard a series of recordings, each featuring a speaker saying several words, all with the same vowel in them.

“Americans often listen to vowels to judge how much of an accent someone has,” Campbell-Kibler said.

For example, some people may pronounce “pen” so that it sounds to others like they are saying “pin.”

In all, participants heard 15 speakers pronounce words like “pass,” “food” and “pen.”

Participants rated each speaker on a scale from “not at all accented” to “very accented.”

Although the participants weren’t told this at the time, all the speakers had grown up in one of three regions of Ohio that linguists have coded as having particular accents: northern Ohio (the Inland North accent), central Ohio (the Midland accent) and southern Ohio (the South accent).

After rating the accents of the people they heard, participants were then asked to rate how accented they thought the speech was in various parts of Ohio on a scale of 0 (no accent) to 100 (very accented). Based on the similarity of answers, Campbell-Kibler was able to collapse them into the three categories of northern, central and southern Ohio.

In general, museum visitors thought people from southern Ohio had the strongest accents, somewhere near 60 to 70 on the scale. Central Ohio residents didn’t have much of an accent, according to participants, with a score averaging 20 to 25. They weren’t sure about northern Ohio residents, who had a score near 50 on the scale.

Results showed that Ohioans take until adulthood to fully absorb these beliefs about the differing accents in the state. The 9-year-old participants didn’t show much differentiation in perceptions between north and south – it took until about age 25 before the beliefs leveled off.

But here is what most interested Campbell-Kibler about the results.

If a person reported that northern Ohioans in general had a strong, noticeable accent – say they rated them 90 on the scale of 0-100 – you would expect that when they heard a recording of a northern Ohioan speaking, they would rate it as very accented.

But that didn’t occur. People who thought northern Ohioans in general had a strong accent didn’t think the accent of the actual northern Ohio speaker they heard was more accented than those from other areas of the state.

The same was true for the other regions in Ohio that were rated.

“Just because people gave a high rating to the idea that people in southern Ohio have an accent, that doesn’t mean they are good at hearing how actual southern Ohioans pronounce vowels differently,” Campbell-Kibler said.

So if people can’t pick up on accents from hearing them directly, then how do they learn about them?

“It is perplexing. We don’t know the full answer for why this is,” Campbell-Kibler said.

But part of the answer may be that we learn about accents culturally, through other people, and through hearing people on TV shows and movies.

“We may hear friends say they have an aunt in Akron who talks funny or hear people on the TV or the movies from Alabama or Britain talk differently than we do,” Campbell-Kibler said.

“We may not be able to identify an accent – we just know something is there because friends are telling stories about it or we hear the characters on TV.

“There’s a lot more we need to learn about how accents are represented cognitively in our brains,” she said.

END

The complicated question of how we determine who has an accent

A disconnect between how people judge speakers versus regions

2025-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NITech researchers shed light on the mechanisms of bacterial flagellar motors

2025-02-13

When speaking of motors, most people think of those powering vehicles and human machinery. However, biological motors have existed for millions of years in microorganisms. Among these, many bacterial species have tail-like structures—called flagella—that spin around to propel themselves in fluids. These movements employ protein complexes known as the “flagellar motor.”

This flagellar motor consists of two main components: the rotor and the stators. The rotor is a large rotating structure, anchored to the cell membrane, that turns the flagellum. On the other hand, the stators are smaller ...

Study maps new brain regions behind intended speech

2025-02-13

Broca’s aphasia is caused by damage to the frontal lobe, leaves patients unable to say what they intend to say

First study to identify regions outside the frontal lobe that encode the intent to speak

Critical for technology to avoid decoding a patient’s thoughts that are not intended to be spoken aloud

CHICAGO --- Imagine seeing a furry, four-legged animal that meows. Mentally, you know what it is, but the word “cat” is stuck on the tip of your tongue.

This phenomenon, known as Broca’s aphasia or expressive aphasia, is a language disorder that affects a person’s ability to speak or ...

Next-gen Alzheimer’s drugs extend independent living by months

2025-02-13

In the past two years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved two novel Alzheimer’s therapies, based on data from clinical trials showing that both drugs slowed the progression of the disease. But while the approvals of lecanemab and donanemab, both antibody therapies that clear plaque-causing amyloid proteins from the brain, were greeted with enthusiasm by some Alzheimer’s researchers, the response of patients has been muted. According to physicians who care for people with Alzheimer’s, many patients found it difficult to understand what the clinical trials results — presented as “percent decrease in ...

Jumping workouts could help astronauts on the moon and Mars, study in mice suggests

2025-02-13

Jumping workouts could help astronauts prevent the type of cartilage damage they are likely to endure during lengthy missions to Mars and the Moon, a new Johns Hopkins University study suggests.

The research adds to ongoing efforts by space agencies to protect astronauts against deconditioning/getting out of shape due to low gravity, a crucial aspect of their ability to perform spacewalks, handle equipment and repairs, and carry out other physically demanding tasks.

The study, which shows knee cartilage in mice grew healthier following jumping exercises, appears ...

Guardian molecule keeps cells on track – new perspectives for the treatment of liver cancer

2025-02-13

A guardian molecule ensures that liver cells do not lose their identity. This has been discovered by researchers from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), the Hector Institute für Translational Brain Research (HITBR), and from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL). The discovery is of great interest for cancer medicine because a change of identity of cells has come into focus as a fundamental principle of carcinogenesis for several years. The Heidelberg researchers were able to show ...

Solar-powered device captures carbon dioxide from air to make sustainable fuel

2025-02-13

Researchers have developed a reactor that pulls carbon dioxide directly from the air and converts it into sustainable fuel, using sunlight as the power source.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, say their solar-powered reactor could be used to make fuel to power cars and planes, or the many chemicals and pharmaceuticals products we rely on. It could also be used to generate fuel in remote or off-grid locations.

Unlike most carbon capture technologies, the reactor developed by the Cambridge researchers does not require fossil-fuel-based power, or the transport and storage of carbon dioxide, but instead converts atmospheric CO2 into something useful using sunlight. ...

Bacteria evolved to help neighboring cells after death, new research reveals

2025-02-13

Darwin’s theory of natural selection provides an explanation for why organisms develop traits that help them survive and reproduce.

Because of this, death is often seen as a failure rather than a process shaped by evolution.

When organisms die, their molecules need to be broken down for reuse by other living things.

Such recycling of nutrients is necessary for new life to grow.

Now a study led by Professor Martin Cann of ...

Lack of discussion drives traditional gender roles in parenthood

2025-02-13

Conversations about parental duties continue to be led by mothers, even if both parents earn the same amount of money, finds a new study by a UCL researcher.

A new study by Dr Clare Stovell (IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education & Society), published in the Journal of Family Studies, highlights how a lack of discussion between parents about important choices such as parental leave, work and childcare is perpetuating traditional gender roles.

The study found that women usually lead the conversations and there is little discussion about the man’s work schedule, even in cases where the woman earns as much or more than her partner.

Dr Stovell said: “These interviews ...

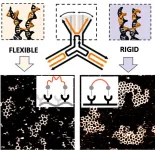

Scientists discover mechanism driving molecular network formation

2025-02-13

Covalent bonding is a widely understood phenomenon that joins the atoms of a molecule by a shared electron pair. But in nature, patterns of molecules can also be connected through weaker, more dynamic forces that give rise to supramolecular networks. These can self-assemble from an initial molecular cluster, or crystal, and grow into large, stable architectures.

Supramolecular networks are essential for maintaining the structure and function of biological systems. For example, to ‘eat’, cells rely ...

Comprehensive global study shows pesticides are major contributor to biodiversity crisis

2025-02-13

Pesticides are causing overwhelming negative effects on hundreds of species of microbes, fungi, plants, insects, fish, birds and mammals that they are not intended to harm – and globally their use is a major contributor to the biodiversity crisis.

That is the finding of the first study assessing the impacts of pesticides across all types of species in land and water habitats, carried out by an international research team that included the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH) and the University of Sussex.

Multiple negative impacts

The scientists analysed over 1,700 existing lab and field studies of the impacts of 471 different ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

Could “cyborg” transplants replace pancreatic tissue damaged by diabetes?

Hearing a molecule’s solo performance

Justice after trauma? Race, red tape keep sexual assault victims from compensation

Columbia researchers awarded ARPA-H funding to speed diagnosis of lymphatic disorders

James R. Downing, MD, to step down as president and CEO of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in late 2026

A remote-controlled CAR-T for safer immunotherapy

UT College of Veterinary Medicine dean elected Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology

AERA selects 34 exemplary scholars as 2026 Fellows

Similar kinases play distinct roles in the brain

New research takes first step toward advance warnings of space weather

Scientists unlock a massive new ‘color palette’ for biomedical research by synthesizing non-natural amino acids

Brain cells drive endurance gains after exercise

[Press-News.org] The complicated question of how we determine who has an accentA disconnect between how people judge speakers versus regions