(Press-News.org) The pallium is the brain region where the neocortex forms in mammals, the part responsible for cognitive and complex functions that most distinguishes humans from other species. The pallium has traditionally been considered a comparable structure among mammals, birds, and reptiles, varying only in complexity levels. It was assumed that this region housed similar neuronal types, with equivalent circuits for sensory and cognitive processing. Previous studies had identified the presence of shared excitatory and inhibitory neurons, as well as general connectivity patterns suggesting a similar evolutionary path in these vertebrate species. However, the new studies have revealed that, although the general functions of the pallium are equivalent among these groups, its developmental mechanisms and the molecular identity of its neurons have diverged substantially throughout evolution.

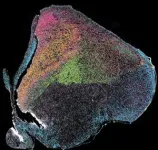

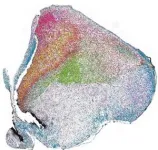

The first study, conducted by Eneritz Rueda-Alaña and Fernando García-Moreno at Achucarro, with the support of a multidisciplinary team of collaborators from the Basque research centers CICbioGUNE and BCAM, the Madrid-based CNIC, the University of Murcia, Krembil (Canada), and Stockholm University, shows that while birds and mammals have developed circuits with similar functions, the way these circuits form during embryonic development is radically different. "Their neurons are born in different locations and developmental times in each species," explains Dr. García-Moreno, head of the Brain Development and Evolution laboratory, "indicating that they are not comparable neurons derived from a common ancestor." Using spatial transcriptomics and mathematical modeling, the researchers found that the neurons responsible for sensory processing in birds and mammals are formed using different sets of genes. "The genetic tools they use to establish their cellular identity vary from species to species, each exhibiting new and unique cell types." This all indicates that these structures and circuits are not homologous, but rather the result of convergent evolution, meaning that "they have independently developed these essential neural circuits through different evolutionary paths."

The second study further explores these differences. Conducted at Heidelberg University (Germany) and co-directed by Bastienne Zaremba, Henrik Kaessmann, and Fernando García-Moreno, it provides a detailed cell type atlas of the avian brain and compares it with those of mammals and reptiles. "We were able to describe the hundreds of genes that each type of neuron uses in these brains, cell by cell, and compare them with bioinformatics tools." The results show that birds have retained most inhibitory neurons present in all other vertebrates for hundreds of millions of years. However, their excitatory neurons, responsible for transmitting information in the pallium, have evolved in a unique way. Only a few neuronal types in the avian brain were identified with genetic profiles similar to those found in mammals, such as the claustrum and the hippocampus, suggesting that some neurons are very ancient and shared across species. "However, most excitatory neurons have evolved in new and different ways in each species," details Dr. García-Moreno.

The studies, published in Science, used advanced techniques in spatial transcriptomics, developmental neurobiology, single-cell analysis, and mathematical modeling to trace the evolution of brain circuits in birds, mammals, and reptiles.

Rewriting the Evolutionary History of the Brain

"Our studies show that evolution has found multiple solutions for building complex brains," explains Dr. García-Moreno. "Birds have developed sophisticated neural circuits through their own mechanisms, without following the same path as mammals. This changes how we understand brain evolution."

These findings highlight the evolutionary flexibility of brain development, demonstrating that advanced cognitive functions can emerge through vastly different genetic and cellular pathways.

The importance of studying brain evolution

"Our brain makes us human, but it also binds us to other animal species through a shared evolutionary history," explains Dr. García-Moreno. The discovery that birds and mammals have developed neural circuits independently has major implications for comparative neuroscience. Understanding the different genetic programs that give rise to specific neuronal types could open new avenues for research in neurodevelopment. Dr. García-Moreno advocates for this type of fundamental research: "Only by understanding how the brain forms, both in its embryonic development and in its evolutionary history, can we truly grasp how it functions."

References:

Rueda-Alaña E, Senovilla-Ganzo R, Grillo M, Vázquez E, Marco-Salas S, Gallego-Flores T, Ftara A, Escobar L, Benguría A, Quintas A, Dopazo A, Rábano M, dM Vivanco M, Aransay AM, Garrigos D, Toval A, Ferrán JL, Nilsson M, Encinas JM, De Pitta M, García-Moreno F (2025). Evolutionary convergence of sensory circuits in the pallium of amniotes. Science (in press). doi: 10.1126/science.adp3411

Zaremba B, Fallahshahroudi A, Schneider C, Schmidt J, Sarropoulos I, Leushkin E, Berki B, Van Poucke E, Jensen P, Senovilla-Ganzo R, Hervas-Sotomayor F, Trost N, Lamanna F, Sepp M, García-Moreno F, Kaessmann H (2025). Developmental origins and evolution of pallial cell types and structures in birds. Science (in press). doi: 10.1126/science.adp5182

For more information or scheduling an interview, please contact:

Dr. Fernando García-Moreno

Achucarro Basque Center for Neuroscience

Fernando.garcia-moreno@achucarro.org

946018139

www.phylobrain.org

END

Birds have developed complex brains independently from mammals

Science publishes two studies led by an Ikerbasque researcher at Achucarro Basque Center for Neuroscience and UPV/EHU that reveal their unique evolution

2025-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Protected habitats aren’t enough to save endangered mammals, MSU researchers find

2025-02-13

Images

EAST LANSING, Mich. – Tropical forests are massive biodiversity storehouses. While these rich swathes of land constitute less than one-tenth of Earth’s surface, they harbor more than 60% of known species. Among them is a higher concentration of endangered species than anywhere else on Earth.

However, these regions are also under immense pressure, as tropical land is rapidly being transformed for industrial and agricultural purposes.

Worldwide, regional governments and international groups are establishing new protected areas to slow further loss of threatened species. However, new research appearing in the journal PLOS Biology demonstrates ...

Scientists find new biomarker that predicts cancer aggressiveness

2025-02-13

HOUSTON ― Using a new technology and computational method, researchers from Fred Hutch Cancer Center and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have uncovered a biomarker capable of accurately predicting outcomes in meningioma brain tumors and breast cancers.

In the study, published today in Science, the researchers discovered that the amount of a specific enzyme, RNA Polymerase II (RNAPII), found on histone genes was associated with tumor aggressiveness and recurrence. Hyper-elevated levels of RNAPII on these histone genes indicate cancer over-proliferation and potentially contribute to chromosomal changes. These findings point to the use of a new genomic technology as ...

UC Irvine astronomers gauge livability of exoplanets orbiting white dwarf stars

2025-02-13

Irvine, Calif., Feb. 13, 2025 — Among the roughly 10 billion white dwarf stars in the Milky Way galaxy, a greater number than previously expected could provide a stellar environment hospitable to life-supporting exoplanets, according to astronomers at the University of California, Irvine.

In a paper published recently in The Astrophysical Journal, a research team led by Aomawa Shields, UC Irvine associate professor of physics and astronomy, share the results of a study comparing the climates of exoplanets at two different stars. One is a hypothetical white dwarf that’s passed through much of its life cycle and is on a slow path ...

Child with rare epileptic disorder receives long-awaited diagnosis

2025-02-13

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute (Duncan NRI) at Texas Children's Hospital, Baylor Genetics and collaborating institutions provided a long-awaited and rare genetic diagnosis in a child with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a type of developmental epileptic encephalopathy (DEE), associated with a severe, complex form of epilepsy and developmental delay.

Their recent study reports that a highly complex rearrangement of fragments from chromosomes 3 and 5 altered the typical organization of genes in the q14.3 region of chromosome ...

WashU to develop new tools for detecting chemical warfare agent

2025-02-13

Mustard gas, also known as sulfur mustard, is one of the most harmful chemical warfare agents, causing blistering of the skin and mucous membranes on contact. Chemists at Washington University in St. Louis have been awarded a $1 million contract with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) to develop a new way to detect the presence of this chemical weapon on the battlefield.

As with many chemical threats, quick identification of sulfur mustard is key to minimizing its damage, according to Jennifer Heemstra, the Charles Allen Thomas Professor of Chemistry in Arts & Sciences and principal investigator of the new DTRA grant.

“It’s ...

Tufts researchers discover how experiences influence future behavior

2025-02-13

Neuroscientists have new insights into why previous experiences influence future behaviors. Experiments in mice reveal that personal history, especially stressful events, influences how the brain processes whether something is positive or negative. These calculations ultimately impact how motivated a rodent is to seek social interaction or other kinds of rewards.

In a first of its kind study, Tufts University School of Medicine researchers demonstrate that interfering with the neural circuits responsible ...

Engineers discover key barrier to longer-lasting batteries

2025-02-13

Lithium nickel oxide (LiNiO2) has emerged as a potential new material to power next-generation, longer-lasting lithium-ion batteries. Commercialization of the material, however, has stalled because it degrades after repeated charging.

University of Texas at Dallas researchers have discovered why LiNiO2 batteries break down, and they are testing a solution that could remove a key barrier to widespread use of the material. They published their findings online Dec. 10 in the journal Advanced Energy Materials.

The team plans first to manufacture LiNiO2 batteries in the lab and ...

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2025

2025-02-13

WASHINGTON — The Society for Neuroscience (SfN) has selected 10 members from a highly competitive applicant pool to participate in the Society’s annual Capitol Hill Day on March 11–13, 2025. The 10 Early Career Policy Ambassadors (ECPAs), representing many career stages and geographic locations, were chosen for their dedication to advocating for the scientific community, their desire to learn more about effective means of advocacy, and their experience as leaders in their labs and community.

The ambassadors are:

Izan Chalen, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Nicole D’Souza, University of California, Riverside

Lana Ruvolo Grasser, PhD, Department ...

YOLO-Behavior: A new and faster way to extract animal behaviors from video

2025-02-13

Collecting video data is the long-established way biologists collect data to measure the behaviour of animals and humans. Videos might be taken of human subjects sitting in front of a camera while eating in a group in the University of Konstanz, or researchers using cameras to measure how often house sparrow parents visit their nests on Lundy Island, UK. All these video datasets have one thing in common: after collecting them, researchers need to painstakingly watch each video, manually mark down who, where and when each behaviour of interest happens—a process known as “annotation”. ...

Researchers identify a brain circuit for creativity

2025-02-13

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Brigham researchers analyzed data from 857 patients across 36 fMRI brain imaging studies and mapped a common brain circuit for creativity.

They derived the circuit in healthy individuals and then predicted which locations of brain injury and neurodegenerative disease might alter creativity.

The study found that changes in creativity in people with brain injury or neurodegenerative disease may depend on the location of injury in reference to the creativity circuit.

A new study led by ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Black soldier fly larvae show promise for safe organic waste removal

People with COPD commonly misuse medications

How periodontitis-linked bacteria accelerate osteoporosis-like bone loss through the gut

Understanding how cells take up and use isolated ‘powerhouses’ to restore energy function

Ten-point plan to deliver climate education unveiled by experts

Team led by UC San Diego researchers selected for prestigious global cancer prize

Study: Reported crop yield gains from breeding may be overstated

Stem cells from human baby teeth show promise for treating cerebral palsy

Chimps’ love for crystals could help us understand our own ancestors’ fascination with these stones

Vaginal estrogen therapy not linked to cancer recurrence in survivors of endometrial cancer

How estrogen helps protect women from high blood pressure

Breaking the efficiency barrier: Researchers propose multi-stage solar system to harness the full spectrum

A new name, a new beginning: Building a green energy future together

From algorithms to atoms: How artificial intelligence is accelerating the discovery of next-generation energy materials

Loneliness linked to fear of embarrassment: teen research

New MOH–NUS Fellowship launched to strengthen everyday ethics in Singapore’s healthcare sector

Sungkyunkwan University researchers develop next-generation transparent electrode without rare metal indium

What's going on inside quantum computers?: New method simplifies process tomography

This ancient plant-eater had a twisted jaw and sideways-facing teeth

Jackdaw chicks listen to adults to learn about predators

Toxic algal bloom has taken a heavy toll on mental health

Beyond silicon: SKKU team presents Indium Selenide roadmap for ultra-low-power AI and quantum computing

Sugar comforts newborn babies during painful procedures

Pollen exposure linked to poorer exam results taken at the end of secondary school

7 hours 18 mins may be optimal sleep length for avoiding type 2 diabetes precursor

Around 6 deaths a year linked to clubbing in the UK

Children’s development set back years by Covid lockdowns, study reveals

Four decades of data give unique insight into the Sun’s inner life

Urban trees can absorb more CO₂ than cars emit during summer

Fund for Science and Technology awards $15 million to Scripps Oceanography

[Press-News.org] Birds have developed complex brains independently from mammalsScience publishes two studies led by an Ikerbasque researcher at Achucarro Basque Center for Neuroscience and UPV/EHU that reveal their unique evolution