(Press-News.org) From punch card-operated looms in the 1800s to modern cellphones, if an object has an “on” and an “off” state, it can be used to store information.

In a computer laptop, the binary ones and zeroes are transistors either running at low or high voltage. On a compact disc, the one is a spot where a tiny indented “pit” turns to a flat “land” or vice versa, while a zero is when there’s no change.

Historically, the size of the object making the “ones” and “zeroes” has put a limit on the size of the storage device. But now, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME) researchers have explored a technique to make ones and zeroes out of crystal defects, each the size of an individual atom for classical computer memory applications.

Their research was published today in Nanophotonics.

“Each memory cell is a single missing atom – a single defect,” said UChicago PME Asst. Prof. Tian Zhong. “Now you can pack terabytes of bits within a small cube of material that's only a millimeter in size.”

The innovation is a true example of UChicago PME’s interdisciplinary research, using quantum techniques to revolutionize classical, non-quantum computers and turning research on radiation dosimeters – most commonly known as the devices that store how much radiation hospital workers absorb from X-ray machines – into groundbreaking microelectronic memory storage.

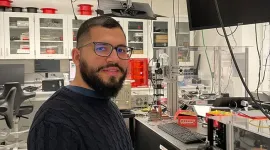

“We found a way to integrate solid-state physics applied to radiation dosimetry with a research group that works strongly in quantum, although our work is not exactly quantum,” said first author Leonardo França, a postdoctoral researcher in Zhong’s lab. “There is a demand for people who are doing research on quantum systems, but at the same time, there is a demand for improving the storage capacity of classical non-volatile memories. And it's on this interface between quantum and optical data storage where our work is grounded.”

From radiation dosimetry to optical storage

The research got its start during França’s PhD research at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. He was studying radiation dosimeters, the devices that passively monitor how much radiation workers in hospitals, synchrotrons and other radiation facilities receive on the job..

“In the hospitals and in particle accelerators, for instance, it’s needed to monitor how much of a radiation dose people are exposed to,” said França. “There are some materials that have this ability to absorb radiation and store that information for a certain amount of time.”

He soon became fascinated about how through optical techniques – shining a light – he could manipulate and “read” that information.

“When the crystal absorbs sufficient energy, it releases electrons and holes. And these charges are captured by the defects,” França said. “We can read that information. You can release the electrons, and we can read the information by optical means.”

França soon saw the potential for memory storage. He brought this non-quantum work into Zhong’s quantum laboratory to create an interdisciplinary innovation using quantum techniques to build classical memories.

“We're creating a new type of microelectronic device, a quantum-inspired technology,” Zhong said.

Rare earth

To create the new memory storage technique, the team added ions of “rare earth,” a group of elements also known as lanthanides, to a crystal.

Specifically, they used a rare-earth element called Praseodymium and an Yttrium oxide crystal, but the process they reported could be used with a variety of materials, taking advantage of rare earths’ powerful, flexible optical properties.

“It’s well known that rare earths present specific electronic transitions that allows you to choose specific laser excitation wavelengths for optical control, from UV up to near-infrared regimes,” França said.

Unlike with dosimeters, which are typically activated by X-rays or gamma rays, here the storage device is activated by a simple ultraviolet laser. The laser stimulates the lanthanides, which in turn release electrons. The electrons are trapped by some of the oxide crystal’s defects, for instance the individual gaps in the structure where a single oxygen atom should be, but isn’t.

“It’s impossible to find crystals – in nature or artificial crystals – that don't have defects,” França said. “So what we are doing is we are taking advantage of these defects.”

While these crystal defects are often used in quantum research, entangled to create “qubits” in gems from stretched diamond to spinel, the UChicago PME team found another use. They were able to guide when defects were charged and which weren’t. By designating a charged gap as “one” and an uncharged gap as “zero,” they were able to turn the crystal into a powerful memory storage device on a scale unseen in classical computing.

“Within that millimeter cube, we demonstrated there are about at least a billion of these memories – classical memories, traditional memories – based on atoms,” Zhong said.

Citation: “All-optical control of charge-trapping defects in rare-earth doped oxides,” França et al, Nanophotonics, February 14, 2025. DOI: 10.1515/nanoph-2024-0635

Funding: This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, for support of microelectronics research, under Contract No. DE-AC0206CH11357

END

Terabytes of data in a millimeter crystal

UChicago Pritzker Molecular Engineering researchers created a "quantum-inspired” revolution in microelectronics, storing classical computer memory in crystal gaps where atoms should be

2025-02-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

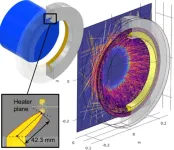

New technology enhances gravitational-wave detection

2025-02-14

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- In a paper published earlier this month in Physical Review Letters, a team of physicists led by Jonathan Richardson of the University of California, Riverside, showcases how new optical technology can extend the detection range of gravitational-wave observatories such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, and pave the way for future observatories.

Since 2015, observatories like LIGO have opened a new window on the universe. Plans for future upgrades to the 4-kilometer LIGO detectors and the construction of a next-generation 40-kilometer observatory, Cosmic Explorer, aim to push the gravitational-wave ...

Gene therapy for rare epilepsy shows promise in mice

2025-02-14

Dravet syndrome and other developmental epileptic encephalopathies are rare but devastating conditions that cause a host of symptoms in children, including seizures, intellectual disability, and even sudden death.

Most cases are caused by a genetic mutation; Dravet syndrome in particular is most often caused by variants in the sodium channel gene SCN1A.

Recent research from Michigan Medicine takes aim at another variant in SCN1B, which causes an even more severe form of DEE.

Mice without the SCN1B gene experience seizures and 100 percent mortality just ...

Scientists use distant sensor to monitor American Samoa earthquake swarm

2025-02-14

In late July to October 2022, residents of the Manu’a Islands in American Samoa felt the earth shake several times a day, raising concerns of an imminent volcanic eruption or tsunami.

An earthquake catalog for the area turned up nothing, because the islands lacked a seismic monitoring network that could measure the shaking and aid seismologists in their search for the source of the earthquake swarm.

But the residents of the Taʻū, Ofu, and Olosega islands needed answers, so Clara Yoon of the ...

New study explains how antidepressants can protect against infections and sepsis

2025-02-14

LA JOLLA (February 14, 2025)—Antidepressants like Prozac are commonly prescribed to treat mental health disorders, but new research suggests they could also protect against serious infections and life-threatening sepsis. Scientists at the Salk Institute have now uncovered how the drugs are able to regulate the immune system and defend against infectious disease—insights that could lead to a new generation of life-saving treatments and enhance global preparedness for future pandemics.

The Salk study follows recent findings that users of selective ...

Research reveals how Earth got its ice caps

2025-02-14

University of Leeds news

Embargoed until 14 February 2025 (19:00 GMT)

---

The cool conditions which have allowed ice caps to form on Earth are rare events in the planet’s history and require many complex processes working at once, according to new research.

A team of scientists led by the University of Leeds investigated why Earth has existed in what is known as a 'greenhouse' state without ice caps for much of its history, and why the conditions we are living in now are so rare.

They found ...

Does planetary evolution favor human-like life? Study ups odds we’re not alone

2025-02-14

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Humanity may not be extraordinary but rather the natural evolutionary outcome for our planet and likely others, according to a new model for how intelligent life developed on Earth.

The model, which upends the decades-old “hard steps” theory that intelligent life was an incredibly improbable event, suggests that maybe it wasn't all that hard or improbable. A team of researchers at Penn State, who led the work, said the new interpretation of humanity’s origin increases the probability ...

Clearing the way for faster and more cost-effective separations

2025-02-14

CLEVELAND—The process of separating useful molecules from mixtures of other substances accounts for 15% of the nation’s energy, emits 100 million tons of carbon dioxide and costs $4 billion annually.

Commercial manufacturers produce columns of porous materials to separate potential new drugs developed by the pharmaceutical industry, for example, and also for energy and chemical production, environmental science and making foods and beverages.

But in a new study, researchers at Case Western Reserve University have found these ...

Researchers develop a five-minute quality test for sustainable cement industry materials

2025-02-14

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new test developed at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign can predict the performance of a new type of cementitious construction material in five minutes — a significant improvement over the current industry standard method, which takes seven or more days to complete. This development is poised to advance the use of next-generation resources called supplementary cementitious materials — or SCMs — by speeding up the quality-check process before leaving the production floor.

Due ...

Three Texas A&M professors elected to National Academy Of Engineering

2025-02-14

Drs. Vanderlei Bagnato, Rodney Bowersox and Don Lipkin from Texas A&M University’s College of Engineering have been elected to the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) Class of 2025, joining 128 new members and 22 international members. This is one of the highest professional honors for engineers.

“Congratulations to Drs. Bagnato, Bowersox and Lipkin for achieving this recognition. This prestigious honor reflects their groundbreaking contributions to engineering and underscores the exceptional talent within our faculty,” said Dr. Robert H. Bishop, vice chancellor and dean of Texas A&M ...

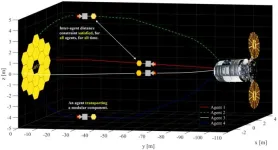

New research sheds light on using multiple CubeSats for in-space servicing and repair missions

2025-02-14

As more satellites, telescopes, and other spacecraft are built to be repairable, it will take reliable trajectories for service spacecraft to reach them safely. Researchers in the Department of Aerospace Engineering in The Grainger College of Engineering, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign are developing a methodology that will allow multiple CubeSats to act as servicing agents to assemble or repair a space telescope. Their method minimizes fuel consumption, guarantees that servicing agents never come closer to each other ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

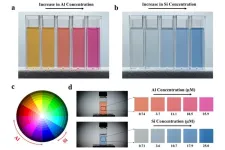

Seeing the unseen: Scientists demonstrate dual-mode color generation from invisible light

Revealing deformation mechanisms of the mineral antigorite in subduction zones

I’m walking here! A new model maps foot traffic in New York City

AI model can read and diagnose a brain MRI in seconds

Researchers boost perovskite solar cell performance via interface engineering

‘Sticky coat’ boosts triple negative breast cancer’s ability to metastasize

James Webb Space Telescope reveals an exceptional richness of organic molecules in one of the most infrared luminous galaxies in the local Universe

The internet names a new deep-sea species, Senckenberg researchers select a scientific name from over 8,000 suggestions.

UT San Antonio-led research team discovers compound in 500-million-year-old fossils, shedding new light on Earth’s carbon cycle

Maternal perinatal depression may increase the risk of autistic-related traits in girls

Study: Blocking a key protein may create novel form of stress in cancer cells and re-sensitize chemo-resistant tumors

HRT via skin is best treatment for low bone density in women whose periods have stopped due to anorexia or exercise, says study

Insilico Medicine showcases at WHX 2026: Connecting the Middle East with global partners to accelerate translational research

From rice fields to fresh air: Transforming agricultural waste into a shield against indoor pollution

University of Houston study offers potential new targets to identify, remediate dyslexia

Scientists uncover hidden role of microalgae in spreading antibiotic resistance in waterways

Turning orange waste into powerful water-cleaning material

Papadelis to lead new pediatric brain research center

Power of tiny molecular 'flycatcher' surprises through disorder

Before crisis strikes — smartwatch tracks triggers for opioid misuse

Statins do not cause the majority of side effects listed in package leaflets

UC Riverside doctoral student awarded prestigious DOE fellowship

UMD team finds E. coli, other pathogens in Potomac River after sewage spill

New vaccine platform promotes rare protective B cells

Apes share human ability to imagine

Major step toward a quantum-secure internet demonstrated over city-scale distance

Increasing toxicity trends impede progress in global pesticide reduction commitments

Methane jump wasn’t just emissions — the atmosphere (temporarily) stopped breaking it down

Flexible governance for biological data is needed to reduce AI’s biosecurity risks

Increasing pesticide toxicity threatens UN goal of global biodiversity protection by 2030

[Press-News.org] Terabytes of data in a millimeter crystalUChicago Pritzker Molecular Engineering researchers created a "quantum-inspired” revolution in microelectronics, storing classical computer memory in crystal gaps where atoms should be