(Press-News.org) A new Colorado State University study of the interior U.S. West has found that tree ranges are generally contracting in response to climate change but not expanding into cooler, wetter climates – suggesting that forests are not regenerating fast enough to keep pace with climate change, wildfire, insects and disease.

As the climate becomes too warm for trees in certain places, tree ranges have been expected to shift toward more ideal conditions. The study analyzed national forest inventory data for more than 25,000 plots in the U.S. West, excluding coastal states, and found that trees were not regenerating in the hottest portions of their ranges – an expected outcome.

More surprising to the researchers was that most of the 15 common tree species studied were not gaining any ground in areas where conditions were more favorable, indicating that most tree species likely will not be able to move to more accommodating climates without assistance.

“Trees provide a lot of value to humans in terms of clean water, clean air, wildlife habitat and recreation,” said lead author Katie Nigro, who conducted the study as a CSU graduate student. "If forest managers want to keep certain trees on the landscape, our study shows where they can still exist or where they might need help.”

Shrinking ranges were prevalent across undisturbed areas as well as those impacted by wildfire, insects and disease. Using 30 years of disturbance data, the researchers tested the idea that disturbances – particularly wildfire – might catalyze tree movement into cooler, wetter areas by killing adult trees and eliminating competition for seedlings to establish in their preferred climate zone.

"Just like us and every species, trees can only function within a certain climatic tolerance, and different species have different climatic tolerances,” Nigro said. “I thought we would find more shifts into cooler zones, especially in burned areas.”

Results of the study, published in Nature Climate Change, give a broad overview of the predominant pattern – an overall failure to regenerate in the hottest, driest portions of a tree’s range, but also failure to expand along the range’s cooler, wetter border. Nigro cautioned that it’s possible not enough time has passed to see new tree establishment in cooler, wetter areas, especially for slow-growing subalpine species. She added that more, local studies are needed to determine which species will survive where.

The paper makes the case for human-assisted tree migration because rapid warming from climate change is likely to outpace regeneration.

"One of the potential issues is that we may get bigger and bigger mismatches between where trees are living and their ideal climate,” Nigro said.

Trees seeking cooler temps face uphill battle

Increasing wildfire, insect and disease disturbances due to climate change also can prevent regeneration by removing seed sources, and seeds literally have an uphill battle in trying to gain ground upslope, where conditions are cooler.

“There's a lot of things that prevent a seed from moving uphill, including gravity,” said co-author Monique Rocca, an associate professor of ecosystem science and sustainability. “A lot of conditions need to be in place for a tree to be able to move to cooler, wetter sites.”

She continued, “This study digs into some of the details of where trees are staying on the landscape on their own versus where we may need to intervene if our goal is to keep Western landscapes covered in trees.”

A few species fared better than others. Of the four species that continued to regenerate in the areas they already occupied regardless of climate change, wildfire, and insect and disease outbreaks, three of them are rarer on the landscape, so it is harder to accurately gauge their response, and one, Gambel oak, is a resilient, heat- and drought-tolerant resprouting species.

The study used long-term field data from the USDA Forest Service’s Forest Inventory and Analysis program, sometimes referred to as the national “tree census.” Study plots on forested areas across the nation are surveyed continuously to track individual tree growth or losses through harvest, disease or death. Kristen Pelz, analysis team lead with the inventory and analysis program, co-authored the study.

“Dr. Nigro harnessed the power of our field-collected data to show how forests are changing across the interior West – not theoretically, but today,” Pelz said. “Her work is important because it considers how things like fire and native insects interact with climate, which is essential where natural disturbances have been a primary driver of forest dynamics for millennia.”

Rather than looking at changes in the average tree range, as past studies have done, this study went a step further and examined the cold and warm margins of species’ ranges – the leading and trailing edges – which specifies how tree ranges are shifting in more detail and provides actionable insights for forest managers. If trees were expanding into cooler areas on their own, assisted migration wouldn’t be as important.

“This research can help land managers and foresters decide whether to hang on to trees in the hottest portions of their ranges for as long as possible or to transition to a more heat- and drought-tolerant system,” Nigro said, adding that sometimes assisted migration can be done with seeds of the same species that are adapted to a warmer environment.

In her current research as an Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education postdoctoral fellow with the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Nigro is trying to identify which seeds from a single species might have the best odds of surviving under harsher climate conditions. Co-author Miranda Redmond, who was Nigro’s Ph.D. adviser at CSU, is also following up on this research by studying tree species adaptations at UC Berkeley.

“These efforts are becoming increasingly critical due to the rapid pace and scale of tree die-offs from wildfires, drought and other climate-driven disturbances, coupled with tree regeneration failures observed in many areas,” Redmond said.

Nigro added, “Planting likely will be required to keep trees on the landscape where they are most valued, and we may need to accept new ecosystems in areas that are inevitably going to change. Our future forests might look different and contain different trees than they do today."

END

Trees might need our help to survive climate change, CSU study finds

2025-02-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Terabytes of data in a millimeter crystal

2025-02-14

From punch card-operated looms in the 1800s to modern cellphones, if an object has an “on” and an “off” state, it can be used to store information.

In a computer laptop, the binary ones and zeroes are transistors either running at low or high voltage. On a compact disc, the one is a spot where a tiny indented “pit” turns to a flat “land” or vice versa, while a zero is when there’s no change.

Historically, the size of the object making the “ones” and “zeroes” has put a limit on the size of the storage device. But now, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular ...

New technology enhances gravitational-wave detection

2025-02-14

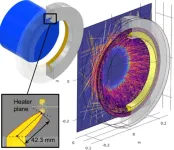

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- In a paper published earlier this month in Physical Review Letters, a team of physicists led by Jonathan Richardson of the University of California, Riverside, showcases how new optical technology can extend the detection range of gravitational-wave observatories such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, and pave the way for future observatories.

Since 2015, observatories like LIGO have opened a new window on the universe. Plans for future upgrades to the 4-kilometer LIGO detectors and the construction of a next-generation 40-kilometer observatory, Cosmic Explorer, aim to push the gravitational-wave ...

Gene therapy for rare epilepsy shows promise in mice

2025-02-14

Dravet syndrome and other developmental epileptic encephalopathies are rare but devastating conditions that cause a host of symptoms in children, including seizures, intellectual disability, and even sudden death.

Most cases are caused by a genetic mutation; Dravet syndrome in particular is most often caused by variants in the sodium channel gene SCN1A.

Recent research from Michigan Medicine takes aim at another variant in SCN1B, which causes an even more severe form of DEE.

Mice without the SCN1B gene experience seizures and 100 percent mortality just ...

Scientists use distant sensor to monitor American Samoa earthquake swarm

2025-02-14

In late July to October 2022, residents of the Manu’a Islands in American Samoa felt the earth shake several times a day, raising concerns of an imminent volcanic eruption or tsunami.

An earthquake catalog for the area turned up nothing, because the islands lacked a seismic monitoring network that could measure the shaking and aid seismologists in their search for the source of the earthquake swarm.

But the residents of the Taʻū, Ofu, and Olosega islands needed answers, so Clara Yoon of the ...

New study explains how antidepressants can protect against infections and sepsis

2025-02-14

LA JOLLA (February 14, 2025)—Antidepressants like Prozac are commonly prescribed to treat mental health disorders, but new research suggests they could also protect against serious infections and life-threatening sepsis. Scientists at the Salk Institute have now uncovered how the drugs are able to regulate the immune system and defend against infectious disease—insights that could lead to a new generation of life-saving treatments and enhance global preparedness for future pandemics.

The Salk study follows recent findings that users of selective ...

Research reveals how Earth got its ice caps

2025-02-14

University of Leeds news

Embargoed until 14 February 2025 (19:00 GMT)

---

The cool conditions which have allowed ice caps to form on Earth are rare events in the planet’s history and require many complex processes working at once, according to new research.

A team of scientists led by the University of Leeds investigated why Earth has existed in what is known as a 'greenhouse' state without ice caps for much of its history, and why the conditions we are living in now are so rare.

They found ...

Does planetary evolution favor human-like life? Study ups odds we’re not alone

2025-02-14

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Humanity may not be extraordinary but rather the natural evolutionary outcome for our planet and likely others, according to a new model for how intelligent life developed on Earth.

The model, which upends the decades-old “hard steps” theory that intelligent life was an incredibly improbable event, suggests that maybe it wasn't all that hard or improbable. A team of researchers at Penn State, who led the work, said the new interpretation of humanity’s origin increases the probability ...

Clearing the way for faster and more cost-effective separations

2025-02-14

CLEVELAND—The process of separating useful molecules from mixtures of other substances accounts for 15% of the nation’s energy, emits 100 million tons of carbon dioxide and costs $4 billion annually.

Commercial manufacturers produce columns of porous materials to separate potential new drugs developed by the pharmaceutical industry, for example, and also for energy and chemical production, environmental science and making foods and beverages.

But in a new study, researchers at Case Western Reserve University have found these ...

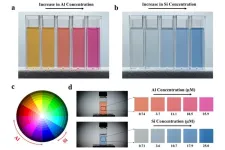

Researchers develop a five-minute quality test for sustainable cement industry materials

2025-02-14

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new test developed at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign can predict the performance of a new type of cementitious construction material in five minutes — a significant improvement over the current industry standard method, which takes seven or more days to complete. This development is poised to advance the use of next-generation resources called supplementary cementitious materials — or SCMs — by speeding up the quality-check process before leaving the production floor.

Due ...

Three Texas A&M professors elected to National Academy Of Engineering

2025-02-14

Drs. Vanderlei Bagnato, Rodney Bowersox and Don Lipkin from Texas A&M University’s College of Engineering have been elected to the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) Class of 2025, joining 128 new members and 22 international members. This is one of the highest professional honors for engineers.

“Congratulations to Drs. Bagnato, Bowersox and Lipkin for achieving this recognition. This prestigious honor reflects their groundbreaking contributions to engineering and underscores the exceptional talent within our faculty,” said Dr. Robert H. Bishop, vice chancellor and dean of Texas A&M ...