(Press-News.org) Acid reducing medicines from the group of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are best-selling drugs that prevent and alleviate stomach problems. PPIs are activated in the acid-producing cells of the stomach, where they block acid production. Researchers at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) made the surprising discovery that zinc-carrying proteins, which are found in all cells, can also activate PPIs – without the presence of gastric acid. The result could be a key to understanding the side effects of PPIs.

Excessive gastric acid can cause not only heartburn, but also chronic complaints such as gastritis or even a stomach ulcer. Doctors usually prescribe a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for treatment. Examples include the medications pantoprazole, omeprazole and rabeprazole. PPIs bind to and block an enzyme in the gastric parietal cells known as the proton pump, effectively reducing the production of gastric acid.

PPIs are prodrugs, which means that they are taken as inactive precursors. Their activation to the actual active substance is triggered by protons. The presence of many protons is the hallmark of an acid. The proton pump in the intestinal wall supplies the protons for acidifying the gastric fluid. Since there is a particularly high concentration of protons in the immediate vicinity of the proton pump, the PPIs are activated locally. Proton-dependent activation ensures that PPIs almost exclusively attack and paralyze the proton pump, at least according to the current doctrine.

Even though short-term use of PPIs is usually very well tolerated and considered harmless, long-term use poses health risks. Studies have suggested the possibility of increased risk of heart attacks, strokes, dementia and susceptibility to infections. This raises the question of whether PPIs are also activated outside the stomach and influence other proteins, i.e. independently of an environment with a high proton concentration.

A team of researchers led by biochemist Tobias Dick and chemist Aubry Miller, both at the DKFZ, have been looking into this question. They used a method known as click chemistry, a strategy for labeling molecules that was awarded the Nobel Prize three years ago. They used it to track rabeprazole, a typical representative of PPIs, in human cells in the culture dish, far from an acidic environment.

In the process, the team made a surprising observation: the PPI was activated in the pH-neutral interior of the cells and bound to dozens of proteins there. Further analysis showed that these were zinc-binding proteins. “This led us to hypothesize that protein-bound zinc can lead to the activation of PPIs, independently of the presence of protons,” explains biologist Teresa Marker, first author of the publication.

In the course of further investigations, the researchers were able to show that protein-bound zinc does in fact form a chemical bond with the PPI, which then leads to the activation of the PPI. The activated PPI is highly reactive and combines on the spot with the zinc-carrying protein. This in turn disrupts the structure and function of the attacked protein.

“From a chemical point of view, this result makes sense, because zinc can mimic the effect of protons and behave like an acid,” explains chemist Aubry Miller of the DKFZ.

Among the zinc-carrying proteins that were most affected by the PPI, some play a role in the immune system. However, further studies are needed to determine whether the newly discovered activation mechanism is associated with the known or suspected side effects of PPIs. “These results open up new perspectives for a better understanding of the side effects of PPIs,” summarizes Tobias Dick.

Publication:

Marker T, Steimbach RR, Perez-Borrajero C, Luzarowski M, Hartmann E, Schleich S, Pastor-Flores D, Espinet E, Trumpp A, Teleman AA, Gräter F, Simon B, Miller AK, Dick TP (2025) Site-specific activation of the proton pump inhibitor rabeprazole by tetrathiolate zinc centers. Nature Chemistry, 2025, DOI: 10.1038/s41557-025-01745-8.

With more than 3,000 employees, the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) is Germany’s largest biomedical research institute. DKFZ scientists identify cancer risk factors, investigate how cancer progresses and develop new cancer prevention strategies. They are also developing new methods to diagnose tumors more precisely and treat cancer patients more successfully. The DKFZ's Cancer Information Service (KID) provides patients, interested citizens and experts with individual answers to questions relating to cancer.

To transfer promising approaches from cancer research to the clinic and thus improve the prognosis of cancer patients, the DKFZ cooperates with excellent research institutions and university hospitals throughout Germany:

National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT, 6 sites)

German Cancer Consortium (DKTK, 8 sites)

Hopp Children's Cancer Center (KiTZ) Heidelberg

Helmholtz Institute for Translational Oncology (HI-TRON Mainz) - A Helmholtz Institute of the DKFZ

DKFZ-Hector Cancer Institute at the University Medical Center Mannheim

National Cancer Prevention Center (jointly with German Cancer Aid)

The DKFZ is 90 percent financed by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and 10 percent by the state of Baden-Württemberg. The DKFZ is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers.

END

Surprising finding for acid reducing drugs

2025-02-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Pushing the limits of ‘custom-made’ microscopy

2025-02-20

A new paper updates an EMBL technology advance even further. More details about the original technology can be found in our initial reporting here.

EMBL tech developers have made an important leap forward with a novel methodology that adds an important microscopy capability to life scientists’ toolbox. The advance represents a 1,000-fold improvement in speed and throughput in Brillouin microscopy and provides a way to view light-sensitive organisms more efficiently.

“We were on a quest to speed up image acquisition,” said Carlo Bevilacqua, lead author on ...

Deep Nanometry reveals hidden nanoparticles

2025-02-20

Researchers including those from the University of Tokyo developed Deep Nanometry, an analytical technique combining advanced optical equipment with a noise removal algorithm based on unsupervised deep learning. Deep Nanometry can analyze nanoparticles in medical samples at high speed, making it possible to accurately detect even trace amounts of rare particles. This has proven its potential for detecting extracellular vesicles indicating early signs of colon cancer, and it is hoped that it can be applied to other medical and industrial fields.

Did you know your ...

Screen time linked to bipolar and manic symptoms in U.S. preteens

2025-02-20

Toronto, ON - Preteens who spend more time on screens are more likely to develop manic symptoms years two-years later, according to a new study published in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology.

The findings reveal that 10- to 11-year-olds who engage heavily with social media, video games, texting, and videos show a greater risk of symptoms such as inflated self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, distractibility, rapid speech, racing thoughts, and impulsivity — behaviors characteristic of manic episodes, a key feature of bipolar-spectrum disorders.

“Adolescence is a particularly ...

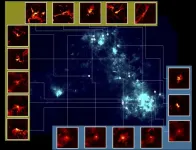

In ancient stellar nurseries, some stars are born of fluffy clouds

2025-02-20

Fukuoka, Japan—How are stars born, and has it always been this way?

Stars form in regions of space known as stellar nurseries, where high concentrations of gas and dust coalesce to form a baby star. Also called molecular clouds, these regions of space can be massive, spanning hundreds of light-years and forming thousands of stars. And while we know much about the life cycle of a star thanks to advances in technology and observational tools, precise details remain obscure. For example, did stars form this way in the early universe?

Publishing in The Astrophysical Journal, researchers from Kyushu University, in collaboration with Osaka Metropolitan ...

Blood pressure drug could be a safer alternative for treating ADHD symptoms, finds study

2025-02-20

Blood pressure drug could be a safer alternative for treating ADHD symptoms, finds study

Repurposing amlodipine, a commonly used blood pressure medicine, could help manage attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms, according to an international study involving the University of Surrey.

In a study published in Neuropsychopharmacology, researchers tested five potential drugs in rats bred to exhibit ADHD-like symptoms. Among them, only amlodipine, a common blood pressure medication, significantly reduced hyperactivity.

To ...

Daily cannabis use linked to public health burden

2025-02-20

WASHINGTON (Feb. 20, 2025)--A new study analyzes the disease burden and the risk factors for severity among people who suffer from a condition called cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Researchers at the George Washington University say the condition occurs in people who are long-term regular consumers of cannabis and causes nausea, uncontrollable vomiting and excruciating pain in a cyclical pattern that often leads to repeated trips to the hospital.

“This is one of the first large studies to examine the burden of disease associated with this cannabis-linked syndrome,” says Andrew Meltzer, professor of emergency medicine ...

A new gene identified in the search for a therapy to treat malignant cardiac arrythmia

2025-02-20

Cardiac arrhythmias affect millions across the world and are responsible for a fifth of all deaths in the Netherlands. Currently there are multiple treatment options, ranging from life-long medication to invasive surgical procedures. Research from Amsterdam UMC and Johns Hopkins University, published today in the European Heart Journal, sets another important step in the hunt for a one-off gene therapy that could improve heart function and protect against arrhythmias.

"Arrhythmias often occur due to slowing of conduction of the electrical impulse through the heart. Rapid impulse conduction is needed for ...

‘Fog harvesting’ could yield water for drinking and agriculture in the world’s driest regions

2025-02-20

With less annual rainfall than 1 mm per year, Chile’s Atacama Desert is one of the driest places in the world. The main water source of cities in the region are underground rock layers that contain water-filled pore spaces which last recharged between 17,000 and 10,000 years ago.

Now, local researchers have assessed if ‘fog harvesting,’ a method where fog water is collected and saved, is a feasible way to provide the residents of informal settlements with much needed water.

“This research represents a notable shift in the ...

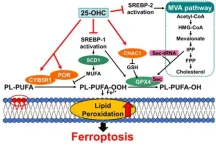

Unveiling the intricate mechanisms behind oxysterol-induced cell death

2025-02-20

Oxysterols are a class of molecules derived from cholesterol via oxidation or as byproducts of cholesterol synthesis. Despite their relatively low concentration within our bodies, oxysterols are known to play many important biological roles, acting as transcriptional regulators, precursors for bile acid, and key players in brain development.

On the flip side, some pathologies are associated with imbalances in oxysterols. In particular, 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-OHC) has been shown to contribute to arteriosclerosis, cancer development, central nervous system ...

Closing the recycle loop: Waste-derived nutrients in liquid fertilizer

2025-02-20

Growing plants can be a joyous, yet frustrating process as plants require a delicate balance of nutrients, sun, and water to be productive.

Phosphorus and nitrogen, which are essential for plant growth, are often supplemented by chemical fertilizers to assure proper balance and output of produce. However, the amount of these nutrients on the planet is increasing due to excessive use, which in turn is causing various environmental problems. For this reason, there is a growing movement to promote sustainable agriculture through the recycling of phosphorus and nitrogen. In Japan, a target has been ...