A new way to engineer composite materials

The innovative polymer design combines strength with reversibility

2025-03-06

(Press-News.org)

— By Rachel Berkowitz

Composite adhesives like epoxy resins are excellent tools for joining and filling materials including wood, metal, and concrete. But there’s one problem: once a composite sets, it’s there forever. Now there’s a better way. Researchers have developed a simple polymer that serves as a strong and stable filler that can later be dissolved. It works like a tangled ball of yarn that, when pulled, unravels into separate fibers.

A new study led by researchers at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) outlines a way to engineer pseudo-bonds in materials. Instead of forming chemical bonds, which is what makes epoxies and other composites so tough, the chains of molecules entangle in a way that is fully reversible. The research is published in the journal Advanced Materials.

“This is a brand new way of solidifying materials. We open a new path to composites that doesn’t go with the traditional ways,” said Ting Xu, a faculty senior scientist at Berkeley Lab and one of the lead authors for the study.

Traditionally, there are two ways to make polymer materials strong and tough. In the first, adding a setting agent creates a crosslinked network of polymer molecules held together by permanent chemical bonds. In the second, increasing the length of polymer molecule chains causes them to get more and more entangled, so they can’t come apart. The latter, Xu proposed, offers the possibility of a reversible design. She likened the concept to folded proteins that interact without chemical bonds to create sturdy structures in nature, and can later unfold into their constituent strands.

Xu along with her colleagues in Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division wanted to build on this concept and start with a collection of simple polystyrene chains, tangle them together into a tough and stable structure, and then take the material back to its starting point. “Let’s say you have a ball of yarn, and it’s a mess. You can’t untangle it,” said Xu. “But if you play with the yarn, maybe you can trick it to untangle.”

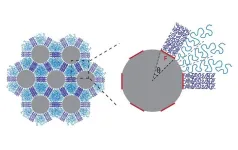

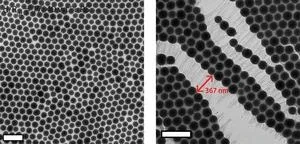

With this in mind, the researchers attached polystyrene chains to hundred-nanometers-diameter silica particles, to create what Xu dubbed “hairy particles.” By forming nanocomposites, these hairy particles self-assembled into a crystal-like structure, providing different spaces between each unit for the hairy polymers to fill. The space available to each polystyrene chain depended on its position in the structure—and, therefore, determined how much it tangled together with its neighbors.

By confining the polymer chains into these tiny spaces with different geometries, Xu reduced the freedom with which any cluster of polystyrene chains could move—thus exercising control over how entangled they became. Or, as it turns out, how not entangled: for certain arrangements, the response to squeezing was that a specific cluster of polystyrene chains loosened up in response to an applied force.

“How much entanglement happens with the particles determines their response to an external force,” said Xu, who is also a professor in UC Berkeley’s College of Engineering and College of Chemistry. By adjusting the polystyrene chain size, as well as precisely where and how many chains were affixed to each facet of the silica particle, she could tweak how the structure responded to dissipate external stresses. Ultimately, these parameters provided the key to engineering entanglement-based “pseudo bonds.”

Microscopy studies revealed that while some chains became rigid under confinement, others ultimately disentangled and stretched to dissipate the external stress. The result was a strong, tough, thin-film material, held firmly together by pseudo bonds of tangled polystyrene chains. Adding small amounts of polystyrene chains themselves to the nanoparticle assemblies increased the final load-bearing properties by another 50%.

“We were really excited that now we can maneuver amorphous polymer organization using nanoconfinement,” said Xu. Until now, amorphous polymers are often randomly entangled, whereas proteins fold nicely. The variations in polystyrene chain arrangement now hits a sweet spot that can be used to engineer composites in a smart way. Moreover, adding a drop of solvent and stirring dissolved the nanocomposite back into its constituent particles suspended: there were no chemical bonds to break, allowing the materials to be reprocessed.

According to Xu, the Berkeley Lab study can readily be extended to other polymers and fillers. Polystyrene is one of the most common polymers and silica is a cheap nanoparticle; nonetheless, Xu hypothesizes that the results will apply to other composites as well. She imagines a future with particles that have other optical or magnetic properties, for example, to create composites for optoelectronic devices. “We can have both strength and toughness, just by modulating how the polymers are distributed,” said Xu.

This research used resources at three DOE Office of Science user facilities at Berkeley Lab: the Advanced Light Source, the Molecular Foundry, and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center. The work was supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science (BES).

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) is committed to groundbreaking research focused on discovery science and solutions for abundant and reliable energy supplies. The lab’s expertise spans materials, chemistry, physics, biology, earth and environmental science, mathematics, and computing. Researchers from around the world rely on the lab’s world-class scientific facilities for their own pioneering research. Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest problems are best addressed by teams, Berkeley Lab and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2025-03-06

WASHINGTON, March 6, 2025—The American Educational Research Association (AERA) has announced the selection of 29 exemplary scholars as 2025 AERA Fellows. The AERA Fellows Program honors scholars for their exceptional contributions to, and excellence in, education research. Nominated by their peers, the 2025 Fellows were selected by the Fellows Committee and approved by the AERA Council, the association’s elected governing body. They will be inducted during a ceremony at the 2025 Annual Meeting in Denver on April 24. With this cohort, there will be a total of 791 AERA Fellows.

“The ...

2025-03-06

A team of researchers from Nottingham Trent University (UK), Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) and Free University of Bozen-Bolzano (Italy) has created washable and durable magnetic field sensing electronic textiles – thought to be the first of their kind – which they say paves the way to transform use in clothing, as they report in the journal Communications Engineering (DOI: 10.1038/s44172-025-00373-x). This technology will allow users to interact with everyday textiles or specialized clothing by simply pointing their finger above a sensor.

The researchers show how they placed tiny flexible ...

2025-03-06

(Toronto, March 6, 2025) JMIR Publications invites submissions to a new theme issue titled Social and Cultural Drivers of Health in Aging Populations in its open access journal JMIR Aging. The premier, peer-reviewed journal is indexed in PubMed, PubMed Central, MEDLINE, DOAJ, Scopus, and the Science Citation Index Expanded (Clarivate).

As aging populations grow worldwide, understanding the social and cultural factors that impact health outcomes in older adults has become a critical area of study. This theme issue aims to highlight the role of digital health ...

2025-03-06

Two new studies led by researchers at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) have uncovered key biological mechanisms driving systemic sclerosis (SSc), or scleroderma – a rare and often devastating autoimmune disease that causes fibrosis (tissue hardening) and inflammation. The research, published in the March issue of the Journal of Experimental Medicine, helps explain why the disease disproportionately affects women and reveals potential treatment targets, some of which are already in development.

Scleroderma affects approximately 300,000 people in the U.S., with about one-third ...

2025-03-06

Miami (March 6, 2025) – Mental health disorders in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are underdiagnosed and undertreated, leading to worsened symptoms and decreased quality of life, according to a new study. The study is published in the January 2025 issue of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases: Journal of the COPD Foundation, a peer-reviewed, open-access journal.

COPD is an inflammatory lung disease, comprising several conditions, including chronic bronchitis and emphysema, and ...

2025-03-06

We commonly consider spiritual practices sources of peace and inspiration. A recent study led by researchers of the University of Vienna shows that they can also be experienced differently: Many persons feel bored during these practices – and this can have far-reaching consequences. The results recently published in the academic journal Communications Psychology open up an entirely new field of research and provide fascinating insights into a phenomenon that has received only scant attention so far.

Even though boredom is a heavily researched subject at the moment, spiritual boredom has so far been largely neglected in research. Psychologists at the University of ...

2025-03-06

The intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) do not attain a stable secondary or tertiary structure and rapidly change their conformation, making structure prediction particularly challenging. These proteins although exhibit chaotic and ‘disordered’ structures, they still perform essential functions.

The IDPs comprise approximately 30% of the human proteome and play important functional roles in transcription, translation, and signalling. Many mutations linked to neurological diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), are located in intrinsically disordered protein regions (IDRs).

Powerful machine-learning algorithms, including ...

2025-03-06

A new study by researchers including those at the University of Tokyo revealed that atmospheric gravity waves play a crucial role in driving latitudinal air currents on Mars, particularly at high altitudes. The findings, based on long-term atmospheric data, offer a fresh perspective on the behaviors of Mars' middle atmosphere, highlighting fundamental differences from Earth’s. The study applied methods developed to explore Earth’s atmosphere to quantitatively estimate the influence of gravity waves on Mars’ planetary circulation.

Despite it being a very cold planet, Mars is quite a hot topic these days. With human visitation seemingly ...

2025-03-06

A team of scientists from University College Cork (UCC) , the University of Connecticut, and the Natural History Museum of Vienna have uncovered how plants responded to catastrophic climate changes 250 million years ago. Their findings, published in GSA Bulletin, reveal the long, drawn-out process of ecosystem recovery following one of the most extreme periods of warming in Earth’s history: the ‘End-Permian Event’.

With more than 80% of ocean species wiped out, the end-Permian event was the worst mass extinction of all time. But the impacts of this event for life on land have been elusive. By examining fossil plants and ...

2025-03-06

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – A new clinical trial will allow researchers to study 3D-printed bioresorbable devices aimed at treating children with rare and life-threatening airway condition tracheobronchomalacia.

The trial, launched by Michigan Medicine and Materialise, marks a crucial step towards full Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the innovative devices designed to support the airways of infants with the severest forms of the disease.

Tracheobronchomalacia causes the airway to collapse, making breathing difficult and, in severe cases, can be fatal. Currently, infants with this ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] A new way to engineer composite materials

The innovative polymer design combines strength with reversibility