(Press-News.org) What do albatrosses searching for food, stock market fluctuations, and the dispersal patterns of seeds in the wind have in common?

They all exhibit a type of movement pattern called Lévy walk, which is characterized by a flurry of short, localized movements interspersed with occasional, long leaps. For living organisms, this is an optimal strategy for balancing the exploitation of nearby resources with the exploration of new opportunities when the distribution of resources is sparse and unknown.

Originally described in the context of particles drifting through liquid, Lévy walk has been found to accurately describe a very wide range of phenomena, from cold atom dynamics to swarming bacteria. And now, a new study published in Complexity has for the first time found Lévy walk in the movements of competing groups of organisms: football teams. “Football is a game about scarcity of resources: to win, a team requires possession of the ball, and there is only one ball in play,” says Professor Tom Froese, senior author of the study and leader of the Embodied Cognitive Science Unit at OIST. “And so, it makes sense for individual players to move in a way that balances exploration and exploitation, ensuring that they do not stay in the same place too long while increasing their chances of getting the ball at each point. We found that the teams as a whole act in exactly the same way.”

From particles in liquid to players on a field

The concept of Lévy walks originated with the French mathematician Paul Lévy, who developed a statistical model of heavy-tailed probability distributions that was later applied by Mandelbrot to describe random movements with occasional long jumps. Lévy walks found their first practical application in physics, where researchers used them to model the movement of particles in turbulent flows, finding that particles following Lévy walk patterns were superdiffusive, meaning that they spread faster due to the occasional long jumps. The concept made a significant leap into biology in 1996, when a study demonstrated that wandering albatrosses exhibit Lévy walks while foraging.

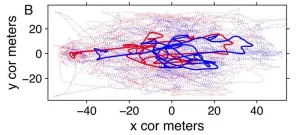

The OIST researchers used data from a match in the top Japanese football league, J-League, which included exact locations of each player and the ball at a centimeter-level precision throughout the game. “We found through statistical tests that the players exhibited Lévy walk when hunting for the ball – much like animals foraging for food. As soon as they got the ball, they deviated from Lévy walk, possibly due to the constraints of interacting with the ball. We saw the same behavior in the team’s centroid—the average position of all players—which suggests that the teams act as an individual agent when seeking possession of the ball,” explains Ivan Shpurov, first author and PhD student in the unit.

In addition to testing the movements of players and teams for Lévy walk, the researchers also found a strong correlation between the degree to which players exhibit Lévy walk and their mean distance to the ball as well as to their team’s centroid, finding that the players with a more prominent Lévy walk pattern were overall closer to both the ball and the team’s centroid. “While we cannot conclude that Lévy walk is the hallmark of a good football player, it does suggest that players who strongly exhibit Lévy walk movement are more active and generally closer to the ball, and contribute better to the team dynamic,” says Shpurov. Differences in the degree of Lévy walk could also provide insights into the distinct player roles. For one, the goalkeeper has a very different movement pattern and role.

One for the team

In finding that not only individual football players but also entire teams act to optimize the balance between exploration and exploitation, the researchers have demonstrated the explanatory power of Lévy walks and provided insights into how we – and other pack-hunting animals – work together to achieve shared goals. “While we haven’t yet investigated the underlying mechanisms of team coherence, previous research has suggested that behavioral cooperation in pairs is often associated with increased interbrain synchrony – the finding that two people can essentially link up their minds to perform a shared activity,” explains Prof. Froese.

The novel finding that a group of individuals can come together and collectively exhibit Lévy walk is evidence of such synchrony, potentially suggesting that we can project our cognition beyond our immediate selves into a collective self that can behave as a single, integrated agent. As Prof. Froese puts it, “the footballers do not all act in exactly the same way, as that would be a highly inefficient tactic. Instead, their individual actions complement one another in response to the game, with the behavior of the team emerging from the individual behaviors of the teammates.”

This collective action could also suggest why team sports are so popular. Given the universality of Lévy walks, which has been observed in 50-million-year-old fossilized trails of sea urchins as well as in the movement patterns of contemporary hunter-gatherers, it’s possible that our fascination with games like football stems from their enactment of very ancient foraging patterns. The ability of individuals to coordinate and adapt their behavior to act as a unified agent in pursuit of a shared goal could also suggest that the fundamental principles of cooperation and efficiency resonate with us at a primal level.

The research not only highlights the observed prevalence of Lévy walks across particles, organisms, and now group behavior, but also opens new avenues for understanding collective dynamics that challenge traditional, single-brain centered views of cognition, showing that players can come together in team that behaves as a collective self.

END

Foraging footballers suggest how we come together to act as one

New study finds football teams move as though they are a single person, offering new insights into collective behavior

2025-03-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

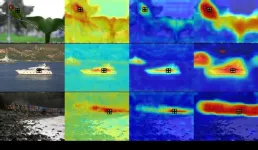

SSA: Semantic Structure Aware Inference for Weakly Pixel-Wise Dense Predictions without Cost

2025-03-11

CAM is proposed to highlight the class-related activation regions for an image classification network, where feature positions related to the specific object class are activated and have higher scores while other regions are suppressed and have lower scores. For specific visual tasks, CAM can be used to infer the object bounding boxes in weakly-supervised object location(WSOL) and generate pseudo-masks of training images in weakly-supervised semantic segmentation (WSSS). Therefore, obtaining the high-quality CAM is very important to improve the recognition performance of weakly supervised pixel-wise ...

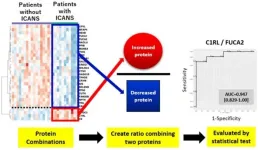

New test helps doctors predict a dangerous side effect of cancer treatment

2025-03-11

Fukuoka, Japan — Medical researchers in Japan have discovered a way to predict a potentially life-threatening side effect of cancer immunotherapy before it occurs. By analyzing cerebrospinal fluid collected pre-treatment, researchers at Kyushu University identified specific proteins associated with a damaging immune response that can affect the central nervous system after therapy. Their findings, published in Leukemia on 11 March, 2025, could make immunotherapy cancer treatment safer by helping doctors identify high-risk patients in advance, ...

UC Study: Long sentences for juveniles make reentry into society more difficult

2025-03-11

Juveniles grow up hearing a multitude of adages about life, such as: “True friends are forever,” “Fake it ’til you make it,” and “Change is a good thing.”

However, these adages — and other life advice about behavior in society — are difficult to process for juveniles who were incarcerated at a young age and served long sentences, says J.Z. Bennett, a criminologist at the University of Cincinnati whose research focuses on prison reform.

“Spending decades in prison removes individuals from social structures and sources of informal social control, such as education, employment, marriage and parenting,” he writes ...

Death by feral cat: DNA shows cats to be culprits in killing of native animals

2025-03-11

Conservation scientists from UNSW Sydney have used DNA technology to identify feral cats as the primary predators responsible for the deaths of reintroduced native animals at two conservation sites in South Australia.

The finding fits in with research data that suggests feral cats have killed more native animals than any other feral predators in Australia, and are believed to be responsible for two thirds of mammal extinctions since European settlement.

But in a study published recently in the ...

Plant Physiology is Searching for its Next Editor-in-Chief

2025-03-10

After taking the helm of Plant Physiology 2022, Yunde Zhao's celebrated term as Editor-in-Chief of the journal, during which he introduced changes that saw the journal flourish, will come to a close on December 31, 2026. The American Society of Plant Biologists (ASPB) is seeking a prominent plant scientist to assume the duties and responsibilities of Editor-in-Chief of Plant Physiology effective January 1, 2027. ASPB’s EIC Search Committee is charged with evaluating candidates for the position and invites members of the plant science community to participate in the process by nominating someone who they ...

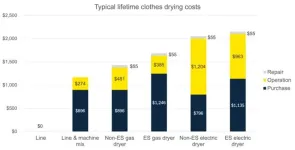

Clothes dryers and the bottom line: Switching to air drying can save hundreds

2025-03-10

Researchers from the University of Michigan are hoping their new study will inspire some Americans to rethink their relationship with laundry. Because, no matter how you spin it, clothes dryers use a lot of comparatively costly energy when air works for free.

Household dryers in the U.S. consume about 3% of our residential energy budget, about six times that used by washing machines. Collectively, dryers cost more than $7 billion to power each year in this country, and generating that energy emits the equivalent of more than ...

New insights into tRNA-derived small RNAs offer hope for digestive tract disease diagnosis and treatment

2025-03-10

This new article published in Genes & Diseases highlights the critical role of tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) in digestive tract diseases, positioning these molecules as potential biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and targeted therapies. The comprehensive review explores the biogenesis, classification, and biological functions of tsRNAs, shedding light on their influence over cellular processes such as translation regulation, epigenetic modification, and protein interactions.

Recent findings emphasize the significance of tsRNAs in both tumor and non-tumor digestive diseases, demonstrating their ability to regulate cell proliferation, ...

Emotive marketing for sustainable consumption?

2025-03-10

Does triggering certain emotions increase willingness to pay for sustainably produced food? In social media, emotional messages are often used to influence users' consumer behaviour. An international research team including the University of Göttingen investigated the short- and medium-term effects of such content on consumers' willingness to pay for bars of chocolate. They found that in the short term, provoking certain emotions increases willingness to pay, but the effect weakens after a very short time. The results were published in the journal Q Open.

Food ...

Prostate cancer is not a death knell, study shows

2025-03-10

Prostate cancer statistics can look scary: 34,250 U.S. deaths in 2024. 1.4 million new cases worldwide in 2022.

Dr. Bruce Montgomery, a UW Medicine oncologist, hopes that patients won’t see these numbers and just throw up their hands in fear or resignation.

“Being diagnosed with prostate cancer is not a death knell,” said Montgomery, senior author of a literature and trial review that appeared in JAMA today. Montgomery is the clinical director of Genitourinary Oncology at Fred Hutch Cancer ...

Unveiling the role of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in endometrial carcinoma

2025-03-10

A new review article published in Genes & Diseases sheds light on the complex molecular mechanisms through which tumor-infiltrating immune cells regulate endometrial carcinoma (EC). As one of the most prevalent gynecological cancers, EC continues to challenge researchers and clinicians due to its dynamic interaction with the immune microenvironment. This comprehensive review presents crucial insights into how immune cells influence tumor progression and how immune evasion strategies enable cancer cells to thrive.

The tumor microenvironment ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

Oak Ridge National Laboratory launches the Next-Generation Data Centers Institute

Improved short-term sea level change predictions with better AI training

UAlbany researchers develop new laser technique to test mRNA-based therapeutics

New water-treatment system removes nitrogen, phosphorus from farm tile drainage

Major Canadian study finds strong link between cannabis, anxiety and depression

[Press-News.org] Foraging footballers suggest how we come together to act as oneNew study finds football teams move as though they are a single person, offering new insights into collective behavior