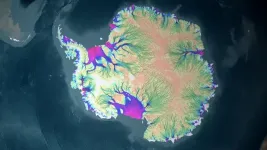

(Press-News.org) As the planet warms, Antarctica’s ice sheet is melting and contributing to sea-level rise around the globe. Antarctica holds enough frozen water to raise global sea levels by 190 feet, so precisely predicting how it will move and melt now and in the future is vital for protecting coastal areas. But most climate models struggle to accurately simulate the movement of Antarctic ice due to sparse data and the complexity of interactions between the ocean, atmosphere, and frozen surface.

In a paper published March 13 in Science, researchers at Stanford University used machine learning to analyze high-resolution remote-sensing data of ice movements in Antarctica for the first time. Their work reveals some of the fundamental physics governing the large-scale movements of the Antarctic ice sheet and could help improve predictions about how the continent will change in the future.

“A vast amount of observational data has become widely available in the satellite age,” said Ching-Yao Lai, an assistant professor of geophysics in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and senior author on the paper. “We combined that extensive observational dataset with physics-informed deep learning to gain new insights about the behavior of ice in its natural environment.”

Ice sheet dynamics

The Antarctic ice sheet, Earth’s largest ice mass and nearly twice the size of Australia, acts like a sponge for the planet, keeping sea levels stable by storing freshwater as ice. To understand the movement of the Antarctic ice sheet, which is shrinking more rapidly every year, existing models have typically relied on assumptions about ice’s mechanical behavior derived from laboratory experiments. But Antarctica’s ice is much more complicated than what can be simulated in the lab, Lai said. Ice formed from seawater has different properties than ice formed from compacted snow, and ice sheets may contain large cracks, air pockets, or other inconsistencies that affect movement.

“These differences influence the overall mechanical behavior, the so-called constitutive model, of the ice sheet in ways that are not captured in existing models or in a lab setting,” Lai said.

Lai and her colleagues didn’t try to capture each of these individual variables. Instead, they built a machine learning model to analyze large-scale movements and thickness of the ice recorded with satellite imagery and airplane radar between 2007 and 2018. The researchers asked the model to fit the remote-sensing data and abide by several existing laws of physics that govern the movement of ice, using it to derive new constitutive models to describe the ice’s viscosity – its resistance to movement or flow.

Compression vs. strain

The researchers focused on five of Antarctica’s ice shelves – floating platforms of ice that extend over the ocean from land-based glaciers and hold back the bulk of Antarctica’s glacial ice. They found that the parts of the ice shelves closest to the continent are being compressed, and the constitutive models in these areas are fairly consistent with laboratory experiments. However, as ice gets farther from the continent, it starts to be pulled out to sea. The strain causes the ice in this area to have different physical properties in different directions – like how a log splits more easily along the grain than across it – a concept called anisotropy.

“Our study uncovers that most of the ice shelf is anisotropic,” said first study author Yongji Wang, who conducted the work as a postdoctoral researcher in Lai’s lab. “The compression zone – the part near the grounded ice – only accounts for less than 5% of the ice shelf. The other 95% is the extension zone and doesn’t follow the same law.”

Accurately understanding the ice sheet movements in Antarctica is only going to become more important as global temperatures increase – rising seas are already increasing flooding in low-lying areas and islands, accelerating coastal erosion, and worsening damage from hurricanes and other severe storms. Until now, most models have assumed that Antarctic ice has the same physical properties in all directions. Researchers knew this was an oversimplification – models of the real world never perfectly replicate natural conditions – but the work done by Lai, Wang, and their colleagues shows conclusively that current constitutive models are not accurately capturing the ice sheet movement seen by satellites.

“People thought about this before, but it had never been validated,” said Wang, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at New York University. “Now, based on this new method and the rigorous mathematical thinking behind it, we know that models predicting the future evolution of Antarctica should be anisotropic.”

AI for Earth science

The study authors don’t yet know exactly what is causing the extension zone to be anisotropic, but they intend to continue to refine their analysis with additional data from the Antarctic continent as it becomes available. Researchers can also use these findings to better understand the stresses that may cause rifts or calving – when massive chunks of ice suddenly break away from the shelf – or as a starting point for incorporating more complexity into ice sheet models. This work is the first step toward building a model that more accurately simulates the conditions we may face in the future.

Lai and her colleagues also believe that the techniques used here – combining observational data and established physical laws with deep learning – could be used to reveal the physics of other natural processes with extensive observational data. They hope their methods will assist with additional scientific discoveries and lead to new collaborations with the Earth science community.

“We are trying to show that you can actually use AI to learn something new,” Lai said. “It still needs to be bound by some physical laws, but this combined approach allowed us to uncover ice physics beyond what was previously known and could really drive new understanding of Earth and planetary processes in a natural setting.”

Other co-authors on this study are from the University of Otago and MIT.

This work was funded by a Stanford Doerr Discovery Grant, the Office of the Dean for Research at Princeton University, the National Science Foundation, NASA, the Schmidt Data X Fund, and the Royal Society of New Zealand.

END

AI reveals new insights into the flow of Antarctic ice

2025-03-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

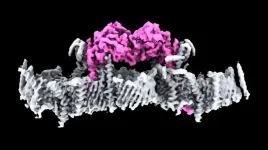

Scientists solve decades-long Parkinson’s mystery

2025-03-13

WEHI researchers have made a huge leap forward in the fight against Parkinson’s disease, solving a decades-long mystery that paves the way for development of new drugs to treat the condition.

First discovered over 20 years ago, PINK1 is a protein directly linked to Parkinson’s disease – the fastest growing neurodegenerative condition in the world. Until now, no one had seen what human PINK1 looks like, how PINK1 attaches to the surface of damaged mitochondria, or how it is switched on.

In ...

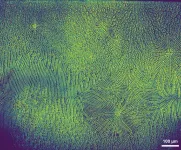

Spinning, twisted light could power next-generation electronics

2025-03-13

Researchers have advanced a decades-old challenge in the field of organic semiconductors, opening new possibilities for the future of electronics.

The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge and the Eindhoven University of Technology, have created an organic semiconductor that forces electrons to move in a spiral pattern, which could improve the efficiency of OLED displays in television and smartphone screens, or power next-generation computing technologies such as spintronics and quantum computing.

The semiconductor they developed emits circularly polarised ...

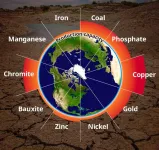

A planetary boundary for geological resources: Limits of regional water availability

2025-03-13

Geological resources such as critical metals and minerals, essential for the diffusion of technologies such as renewable energy and energy storage towards a decarbonized society, are indispensable for supporting modern life in the form of various products and services. Their demand is expected to increase in the coming years owing to global population as well as economic growth. Thus far, scientists and policymakers have primarily discussed geological resource availability from the viewpoint of reserves and resources in the ecosphere and technosphere. However, resources such as ...

Astronomy’s dirty window to space

2025-03-13

When we observe distant celestial objects, there is a possible catch: Is that star I am observing really as reddish as it appears? Or does the star merely look reddish, since its light has had to travel through a cloud of cosmic dust to reach our telescope? For accurate observations, astronomers need to know the amount of dust between them and their distant targets. Not only does dust make objects appear reddish (“reddening”), it also makes them appear fainter than they really are (“extinction”). It’s like we are looking out into space through a dirty ...

New study reveals young, active patients who have total knee replacements are unlikely to need revision surgery in their lifetime

2025-03-13

A 40-year study by Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) researchers has found that active young adults who underwent total knee replacement were unlikely to require knee replacement revision in their lifetime, according to a new study shared today in a podium presentation at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2025 Annual Meeting.1

“As an increasing number of younger adults in their 40s and 50s consider total knee replacement, many wonder how long knee implants last before requiring a revision procedure,” ...

Thinking outside the box: Uncovering a novel approach to brainwave monitoring

2025-03-13

ROCHESTER, Minnesota — Mayo Clinic researchers have found a new way to more precisely detect and monitor brain cell activity during deep brain stimulation, a common treatment for movement disorders such as Parkinson's disease and tremor. This precision may help doctors adjust electrode placement and stimulation in real time, providing better, more personalized care for patients receiving the surgical procedure. The study is published in the Journal of Neurophysiology.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) involves implanting electrodes in the brain that emit electrical pulses to alleviate symptoms. The electrodes remain inside the brain connected to a battery implanted near ...

Combination immunotherapy before surgery may increase survival in people with head and neck cancer

2025-03-13

CHAPEL HILL, North Carolina—Researchers conducting a clinical trial of immunotherapy drugs for people with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) found that patients responded better to a combination of two immunotherapies than patients who received just one immunotherapy drug.

The scientists also analyzed immune cells in each person’s tumor after one month of immunotherapy to see which type of immune cells were activated to fight their cancer, suggesting that some of the cells and targets they identified could help individualize treatment benefit.

The findings appeared March 13, 2025 in Cancer Cell.

HNSCCs occur in the oral cavity, pharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, nasal ...

MIT engineers turn skin cells directly into neurons for cell therapy

2025-03-13

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Converting one type of cell to another — for example, a skin cell to a neuron — can be done through a process that requires the skin cell to be induced into a “pluripotent” stem cell, then differentiated into a neuron. Researchers at MIT have now devised a simplified process that bypasses the stem cell stage, converting a skin cell directly into a neuron.

Working with mouse cells, the researchers developed a conversion method that is highly efficient and can produce more than 10 neurons from a single skin cell. If replicated in human ...

High sugar-sweetened beverage intake and oral cavity cancer in smoking and nonsmoking women

2025-03-13

About The Study: High sugar-sweetened beverage intake was associated with a significantly increased risk of oral cavity cancer in women, regardless of smoking or drinking habits, yet with low baseline risk in this study. Additional studies are needed in larger cohorts, including males, to validate the impact of these findings.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Brittany Barber, MD, MSc, email bbarber1@uw.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2024.5252)

Editor’s ...

Area socioeconomic status, vaccination access, and female HPV vaccination

2025-03-13

About The Study: In this cross-sectional study of area deprivation, vaccination access, and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination status in Osaka City, Japan, higher socioeconomic status and higher medical facility access were associated with higher cumulative HPV vaccination uptake. These findings suggest that further strategies, including a socioecologic approach, are needed to increase HPV vaccination and reduce disparities in uptake.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding ...