(Press-News.org) FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Key Takeaways:

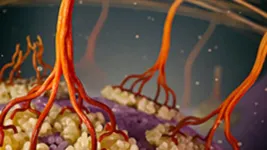

Bacteria get invaded by viruses called phages.

Scientists are studying how bacteria use CRISPR to defend themselves from phages, which will inform new phage-based treatments for bacterial infections that are resistant to antibiotics.

Bacteria seize genetic material from weakened, dormant phages and use it to form a biological “memory” of the invader that their offspring inherit and use for anti-phage defense.

Like people, bacteria get invaded by viruses. In bacteria, the viral invaders are called bacteriophages, derived from the Greek word for bacteria-eaters, or in shortened form, “phages.” Scientists have sought to learn how the single-cell organisms survive phage infection in a bid to further understand human immunity and develop ways to combat diseases.

Now, Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists say they have shed new light on how bacteria protect themselves from certain phage invaders — by seizing genetic material from weakened, dormant phages and using it to “vaccinate” themselves to elicit an immune response.

In their experiments, the scientists say Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria (which cause strep throat) take advantage of a class of phages known as temperate phages, which can either kill cells or become dormant. The bacteria steal genetic material from temperate phages during this dormant period and form a biological “memory” of the invader that their offspring inherit as the bacteria multiply. Equipped with these memories, the new population can recognize these viruses and fight them off.

A report on the experiments, supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, was published March 12 in the journal Cell Host & Microbe. The findings help scientists better understand how bacterial cells that cause serious diseases, including Staph and E. coli infections and cholera, become toxic to humans — a process that involves toxic genes expressed by otherwise dormant phages that reside within the bacterial cell, says corresponding author Joshua Modell, Ph.D., associate professor of molecular biology and genetics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“We essentially wanted to answer the question: If bacterial cells don’t have any memory, or survival skills, to combat a new temperate phage that shows up, how do they buy themselves enough time to establish a new memory, before they succumb to that initial infection?” says Modell.

The Johns Hopkins investigators say bacteria have long been known to use CRISPR-Cas systems to chop up phage DNA, break it down and get rid of it. Crucially, CRISPR systems can only destroy DNA that matches a “memory” captured from a prior infection and stored within the bacteria’s own genome, say the researchers. In this way, the CRISPR system acts as a recording device that documents the long list of foreign invaders encountered by a particular bacterial strain.

To conduct their research, the scientists say they infected populations of bacteria with naturally occurring phages that go dormant or genetically engineered non-dormant phages in separate flasks that contained millions of bacterial cells.

“Our results indicate that the bacteria’s CRISPR system was more effective at using the naturally dormant phage to pull parts of the viral genetic code into their genome,” says Modell. “When we tested phages that could not go dormant, the CRISPR system did not work nearly as well.”

After isolating the bacteria that survived, and letting the survivors repopulate the flask, the scientists used genome sequencing to catalog hundreds of thousands of new DNA memories that the CRISPR Cas9 system had created from the test phages, honing in on those that contribute to cell immunity. The scientists also determined that bacteria created those memories during the temperate phage’s dormancy period, when it did not pose a threat to the population.

“This is conceptually similar to a vaccine with an attenuated virus,” says Nicholas Keith, a graduate student and first author of the paper. “We believe this is the reason why the CRISPR Cas9 system has a unique relationship with this specific class of temperate phage.”

“We can use these types of experiments to find what elements of the phage, the bacterial host and its CRISPR system are important for all stages of bacterial immunity,” Keith says.

In future experiments, the scientists aim to learn more about how CRISPR systems protect bacteria cells from viruses that don’t go dormant, Modell says.

“We know CRISPR systems are one of the first lines of defense against the transfer of hazardous genes from phages that turn bacterial cells toxic,” says Modell. “Furthermore, our studies will inform the design of ‘phage therapies’ which could be used in clinical cases where a bacterial infection is resistant to all available antibiotics.”

In addition to Keith and Modell, study contributors are Rhett Snyder from Johns Hopkins and Chad Euler from Hunter College.

The research was funded by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM142731), the Rita Allen Foundation and the National Science Foundation.

END

New study sheds light on how bacteria ‘vaccinate’ themselves with genetic material from dormant viruses

2025-03-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Four advances that could change tuberculosis treatment

2025-03-21

As of early 2025, tuberculosis cases are increasing in the U.S. This disease, often shortened to TB, causes significant lung damage and, if not treated, is almost always lethal. World TB Day on March 24 raises awareness about the disease and commemorates Robert Koch’s discovery of the source bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. More than a century later, scientists continue refining TB diagnosis methods and treatment strategies, some of which are in these four ACS journal articles. Reporters can request free access to these papers by emailing newsroom@acs.org.

Fluorescence ...

Obesity Action Coalition & The Obesity Society send letter to FDA on behalf of more than 20 leading organizations & providers urging enforcement of compounding regulations

2025-03-21

March 19, 2025 — Today, the Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) and The Obesity Society (TOS) sent a letter to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA), along with more than 20 leading organizations and providers across the healthcare continuum, urging the agency to enforce federal regulations around compounding following the recent resolution of GLP-1 medicine shortages. Among the signatories include: the Alliance for Women’s Health & Prevention, the Association of Black Cardiologists, the National Hispanic Medical Association and the National Consumers League.

The letter follows recent announcements from the FDA that Eli Lilly’s ...

New Microbiology Society policy briefing on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) in wastewater

2025-03-21

AMR occurs when disease-causing bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites (pathogens) are no longer affected by the medicines that have been developed to target them. Drug-resistant pathogens can cause infections that are difficult or impossible to treat; they increase the risk of disease spread and can lead to severe illness, disability and death.

Wastewater is commonly contaminated with antimicrobial resistant micro-organisms and antimicrobial compounds. Upon entering our environment, such as rivers and seas, contaminated wastewater therefore serves as a pathway for, and major contributor to, the spread of AMR in the UK and ...

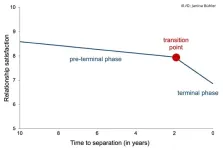

Transition point in romantic relationships signals the beginning of their end

2025-03-21

The end of a romantic relationship usually does not come out of the blue but is indicated one or two years before the breakup. As the results of a psychological study have demonstrated, the terminal stage of a relationship consists of two phases. First, there is a gradual decline in relationship satisfaction, reaching a transition point one to two years before the dissolution of the relationship. "From this transition point onwards, there is a rapid deterioration in relationship satisfaction. Couples in question then move towards separation," said Professor ...

Scientists witness living plant cells generate cellulose and form cell walls for the first time

2025-03-21

In a groundbreaking study on the synthesis of cellulose – a major constituent of all plant cell walls – a team of Rutgers University-New Brunswick researchers has captured images of the microscopic process of cell-wall building continuously over 24 hours with living plant cells, providing critical insights that may lead to the development of more robust plants for increased food and lower-cost biofuels production.

The discovery, published in the journal Science Advances, reveals a dynamic process never seen before and may provide practical applications for everyday products derived from plants including ...

Mount Sinai-led team identifies cellular mechanisms that may lead to onset of inflammatory bowel disease

2025-03-21

A research team led by Mount Sinai has uncovered mechanisms of abnormal immune cell function that may lead to Crohn’s disease, according to findings published in Science Immunology on March 21. The researchers said their discovery provides better understanding of disease development and could inform the development and design of new therapies to prevent inflammation before it starts in the chronic disorder.

Crohn’s disease is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that causes chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and symptoms can include abdominal ...

SNU-GU researchers jointly develop a liquid robot capable of transformation, separation, and fusion like living cells

2025-03-21

A liquid robot capable of transforming, separating, and fusing freely like living cells has been developed.

Seoul National University College of Engineering announced that a joint research team led by Professor Ho-Young Kim from the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Professor Jeong-Yun Sun from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and Professor Keunhwan Park from the Department of Mechanical, Smart, and Industrial Engineering at Gachon University has successfully developed a next-generation ...

Climate warming and heatwaves accelerate global lake deoxygenation, study reveals

2025-03-21

Freshwater ecosystems require adequate oxygen levels to sustain aerobic life and maintain healthy biological communities. However, both long-term climate warming and the increasing frequency and intensity of short-term heatwaves are significantly reducing surface dissolved oxygen (DO) levels in lakes worldwide, according to a new study published in Science Advances.

Led by Prof. SHI Kun and Prof. ZHANG Yunlin from the Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in collaboration with researchers from the Nanjing University and the UK’s ...

Unlocking dopamine’s hidden role: Protective modification of Tau revealed

2025-03-21

Peking University, March 19, 2025: The research group led by Prof. Wang Chu from the College of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering at Peking University published a research article entitled “Quantitative Chemoproteomics Reveals Dopamine’s Protective Modification of Tau” in Nature Chemical Biology (DOI:10.1038/s41589-025-01849-9). Using a novel quantitative chemoproteomic strategy, the team uncovered a protective role of dopamine (DA) in regulating the function of the microtubule-associated protein Tau. This discovery deepens our understanding of dopamine’s physiological and pathological roles in the human brain.

Why it matters:

1. Dopamine, ...

New drug therapy combination shows promise for advanced melanoma patients

2025-03-21

A federally funded research team led by Sheri Holmen, PhD, investigator at Huntsman Cancer Institute and professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Utah (the U), is testing a new combination drug therapy that could both treat and prevent melanoma metastasis, or spreading from its original site, to the brain.

“Once melanoma has spread to the brain, it’s very hard to treat. Metastasis to the brain is one of the main causes of death from melanoma,” says Holmen. “We wanted to find a solution to an unmet clinical need for those patients who had no other treatment options ...