It does so not by being catabolized, or broken down, to release the energy sequestered in its chemical bonds, but instead by binding in its intact form to proteins that control which genes in the genome are made into proteins and when.

The discovery of glucose’s undercover double life was so surprising the researchers spent several years confirming their findings before publishing their results.

“At first we just didn’t believe it,” said Paul Khavari, MD, PhD, chair of dermatology. “But the results of extensive follow-up experiments were clear: Glucose interacts with hundreds of proteins throughout the cell and modulates their function to promote differentiation.”

Understanding this new role for glucose has implications for the treatment of diabetes, in which blood sugar levels are elevated, and cancers, which are often made up largely of undifferentiated cells.

Khavari, who is the Carl J. Herzog Professor in Dermatology in the School of Medicine and a member of the Stanford Cancer Institute, is the senior author of the research, which was published online March 21 in Cell Stem Cell. Research scientist Vanessa Lopez-Pajares, PhD, is the lead author of the study.

A serendipitous finding

Khavari and Lopez-Pajares didn’t have glucose in their crosshairs when they began looking for molecules that drive cellular differentiation. Coupling a technique called mass spectrometry with high-throughput screening methods, they studied the rise and fall of thousands of biomolecules in human skin stem cells as the cells differentiated into mature keratinocytes — the main type of cell in the outermost layer of our skin. Molecules that increase significantly in abundance during the differentiation process might play a role in that transition, they reasoned.

The researchers identified 193 suspect molecules, many of which had been previously associated with differentiation. But the second-most elevated molecule was a surprise.

“When we saw glucose at the top of that list, we were stunned,” Khavari said. “We had expected glucose levels to decrease during differentiation because the cells begin to divide less rapidly, and their energy requirements are less. They are on the path to senescence and death. Yet glucose levels in the cells increase significantly as they move from epidermal stem cells to differentiated keratinocytes.”

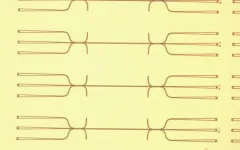

This unexpected glucose increase was confirmed when the researchers measured the cells’ uptake of fluorescent or radioactive glucose analogs and the response of biological sensors within the cells that glow green or red in the presence of biologically relevant concentrations of glucose. As differentiation proceeded, the cells glowed more intensely. Further studies in other human cell types, including developing fat, bone and white blood cells, as well as mice genetically engineered to express fluorescent glucose sensors, showed similar patterns.

“In every tissue we studied, glucose levels increase as the cells differentiate,” Khavari said. “It seems that glucose plays a global role in tissue differentiation throughout the body.”

Additional experiments showed that the increase in glucose within the cells was due to both an increase in glucose import as well as decreased glucose export. They also confirmed that the changes in glucose levels were not accompanied by an increase in the breakdown of glucose into its metabolic byproducts.

Intrigued, the researchers began to directly investigate the effect of changing glucose levels on keratinocyte differentiation under a variety of conditions. They found that human skin organoids — engineered skin tissue grown in liquid that mimic the cellular composition and organization of native skin — were unable to differentiate properly when glucose levels were lower than normal. A closer look found that the expression of over 3,000 genes in the cells was affected by the low glucose levels; many of these genes encoded proteins known to be involved in skin differentiation.

Differentiation of organoid skin resumed when they were grown in a liquid containing a glucose analog that cannot be metabolized by the cells — again showing that the effect on cell differentiation is separate from glucose’s role as an energy source.

“That was really the biggest shock,” Khavari said, “because we were stuck in the mindset that glucose is an energy source and nothing else. But these glucose analogs support differentiation just as well as regular glucose.”

Hints of glucose’s role

There have been inklings of glucose’s behind-the-scenes role. Embryonic stem cells, which can differentiate into every cell in the body, lose this ability when grown in the presence of high levels of glucose — presumably because the increased glucose stimulates the cells to differentiate and lose their “stemness.” Additionally, people with high-glucose levels due to diabetes often experience impaired wound healing and tissue regeneration.

Furthermore, some glucose analogs have shown promise in preclinical and clinical trials as anticancer therapies. Although they were developed to starve cancer cells of energy, these new findings suggest they may instead drive immature cancer cells to differentiate.

Digging deeper, Lopez-Pajares, Khavari and their colleagues found that glucose levels increase due to a boost in production of a protein that transports glucose from the outside of the cell to its interior. Once inside, glucose binds to hundreds of proteins, including one called IRF6, that increase the expression of many genes involved in differentiation. When glucose binds to IRF6, it causes the protein to change its conformation in a way that changes its ability to influence gene expression and drive differentiation.

“We’re seeing glucose acting like a broadcast signal in the cell, in contrast to the highly specific signaling cascades that drive many cellular functions,” Khavari said. “When glucose levels rise in a cell, they rise everywhere, all at once. It’s like a fire alarm going off in a firehouse. Everyone in the firehouse activates in response.”

The researchers are hoping to learn more about how glucose functions in diseased and healthy cells.

“This finding is a springboard for research on dysregulation of glucose levels, which affects hundreds of millions of people,” Khavari said. “But it’s also likely to be important in cancer development because cancer is a disease of failed differentiation. This is an entirely new and growing field. People have thought that small biomolecules like glucose were quite passive in the cell. This is another piece of evidence to pay close attention to other roles these molecules might play.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01AR043799, AR045192, K01AR070895 and P30CA124435) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development.

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END