(Press-News.org) A pan-Canadian team has developed a new way to quickly find personalized treatments for young cancer patients, by growing their tumours in chicken eggs and analyzing their proteins.

The team, led by researchers from the University of British Columbia and BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, is the first in Canada to combine these two techniques to identify and test a drug for a young patient's tumour in time for their treatment.

Their success in finding a new drug for the patient, described today in EMBO Molecular Medicine, shows how the study of proteins, known as proteomics, can be a valuable complement to the established study of genes (genomics) in real-time cancer therapies.

The work was a collaborative effort of PROFYLE (PRecision Oncology For Young peopLE), a key initiative of the Canadian pediatric cancer network ACCESS (Advancing Childhood Cancer Experience, Science and Survivorship) that brings together more than 30 research and funding organizations and over 100 investigators from across Canada to improve cancer outcomes for children and young adults.

The study by co-lead authors Dr. Georgina Barnabas, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Philipp Lange’s lab, and Tariq Bhat, a PhD student in Dr. James Lim’s lab, focused on an unnamed patient diagnosed with a rare pediatric cancer that resisted conventional treatments.

Proteomics: A complementary approach to identify treatment

While genes carry the instructions to make proteins, proteins themselves are the functional building blocks of our cells. Most drugs work by changing the activity of proteins, so the team wondered if proteomics could uncover hidden weaknesses in tumours that genetic testing alone might miss.

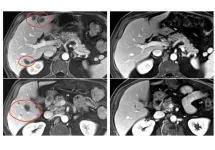

After standard chemotherapy had failed and the tumour became resistant to a drug selected by genomics, no clear drug candidates emerged from further genetic testing. But instead of stopping there, the team turned to proteomics and discovered that the tumour’s metabolism relied heavily on an enzyme known as SHMT2.

“With genomics alone, we couldn’t find a clear treatment option,” said Dr. Lange, who, along with Dr. Lim and clinician Dr. Rebecca Deyell, are senior investigators with the Michael Cuccione Childhood Cancer Research Program at BCCHR. “But by looking at the tumour’s proteins, we found a critical metabolic weakness that we could target with an already approved drug.”

The researchers’ strategy was to use sertraline, a common antidepressant, to inhibit SHMT2 and cut off the tumour’s access to a key energy source.

Replicating the tumour on a chicken egg

To test their idea, the team used a method that involves growing a small piece of the patient’s tumour on a chicken egg, serving as an avatar host for the tumour. Growing an identical tumour outside the patient gave them a way to test for personalized drug responses in a matter of weeks.

“This technique speeds up the process of evaluating a treatment option in a way that simply wouldn’t be possible with traditional methods,” said Dr. Lim. “We could quickly confirm whether the drug we identified through proteomics could actually work for the patient’s tumour.”

The chicken egg avatars are part of the BRAvE initiative (Better Responses through Avatars and Evidence) at BCCHR, which connects clinics with research labs at the hospital.

The team presented their results to a panel of experts established by PROFYLE, who considered sertraline as the best treatment option for the patient at the time.

Encouraging results, but more work to be done

The results were promising but not a cure. After beginning sertraline treatment, the patient’s tumour growth slowed but did not stop, meaning additional treatment was still needed.

“While there is more work to be done, this study shows that our approach can deliver personalized treatment recommendations fast enough to actually help patients with rare and difficult-to-treat cancers,” said Dr. Lange. “We now hope to expand this method to other children to identify effective treatments faster across the country.”

About UBC

The University of British Columbia is a global centre for research and teaching, consistently ranked among the top public universities in the world. Since 1915, UBC’s entrepreneurial spirit has embraced innovation and challenged the status quo. UBC encourages its students, staff and faculty to challenge convention, lead discovery and explore new ways of learning. At UBC, bold thinking is given a place to develop into ideas that can change the world.

About BC Children's Hospital Research Institute

BC Children's Hospital Research Institute conducts discovery, translational and clinical research to benefit the health of children and their families. We are supported by BC Children's Hospital Foundation; are part of BC Children’s Hospital and the Provincial Health Services Authority; and work in close partnership with the University of British Columbia. For more information, visit www.bcchr.ca.

About ACCESS

ACCESS is a pan-Canadian pediatric cancer network advancing childhood cancer experience, science and survivorship. Our network of researchers, healthcare providers, partner organisations, and Persons With Lived Experience believe in equitable access to scientific advances, diagnostic tools, innovative therapies, and supportive care to better health outcomes and quality of life for children with cancer and their families. Visit accessforkidscancer.ca for more information. ACCESS is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

END

Researchers develop new way to match young cancer patients with the right drugs

2025-04-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New 3D technology paves way for next-generation eye-tracking

2025-04-01

Eye tracking plays a critical role in the latest virtual and augmented reality headsets and is an important technology in the entertainment industry, scientific research, medical and behavioral sciences, automotive driving assistance and industrial engineering. Tracking the movements of the human eye with high accuracy, however, is a daunting challenge.

Researchers at the University of Arizona Wyant College of Optical Sciences have now demonstrated an innovative approach that could revolutionize eye-tracking ...

Diagnosing a dud may lead to a better battery

2025-04-01

It’s (going to be) electric.

But how soon? How quickly our society can maximize the benefit of electrification hinges on finding cheaper, higher performance batteries — a reality closer to hand through new research from Virginia Tech.

A team of chemists led by Feng Lin and Louis Madsen found a way to see into battery interfaces, which are tight, tricky spots buried deep inside the cell. The research findings were published on April 1 in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

“There are major, longstanding challenges at the interfaces,” ...

We know nanoplastics are a threat—this new tool can help us figure out just how bad they are

2025-04-01

April 1, 2025

AMHERST, Mass. – While the threat that microplastics pose to human and ecological health has been richly documented and is well known, nanoplastics, which are smaller than one micrometer (1/50th the thickness of an average human hair), are far more reactive, far more mobile and vastly more capable of crossing biological membranes. Yet, because they are so tiny and so mobile, researchers don’t yet have an accurate understanding of just how toxic these particles are. The first step to understanding the toxicology of nanoplastics is to build a reliable, ...

Mpox could become a serious global threat, scientists warn

2025-04-01

Mpox has the potential to become a significant global health threat if taken too lightly, according to scientists at the University of Surrey.

In a letter published in Nature Medicine, researchers highlight how mpox – traditionally spread from animals to humans – is now showing clear signs of sustained human-to-human transmission.

Mpox is a viral infection caused by a virus that belongs to the same family as smallpox. The virus can cause a painful rash, fever, and swollen glands and, in some cases, lead to more serious illness. Mpox usually spreads through ...

Combination immunotherapy shrank a variety of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers

2025-04-01

A new form of tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy, a form of personalized cancer immunotherapy, dramatically improved the treatment’s effectiveness in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal cancers, according to results of a clinical trial led by researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The findings, published April 1, 2025 in Nature Medicine, offer hope that this therapy could be used to treat a variety of solid tumors, which has so far eluded researchers developing cell-based ...

Newborn warty birch caterpillars defend the world’s smallest territory

2025-04-01

Real estate is precious. Some creatures defend territories extending over several kilometres, but when Jayne Yack (Carleton University, Canada) encountered miniature newborn warty birch caterpillars (Falcaria bilineata) she wondered if she might have discovered one of the world’s smallest, and youngest, territorial critters. ‘We had noticed that tiny warty birch caterpillars produced vibrations’, says Yack, who first encountered the feisty little creatures in 2008. She also noticed that the tiny caterpillars – 1 to 2 mm long – reside in solitude on birch leaves, making her speculate whether they ...

Exposure to air pollution in childhood is associated with reduced brain connectivity

2025-04-01

A new study led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), a centre supported by the "la Caixa" Foundation, has found that children exposed to higher levels of air pollution in early and mid childhood have weaker connections between key brain regions. The findings, published in Environment International, highlight the potential impact of early exposure to air pollution on brain development.

The research showed reduced functional connectivity within and between certain cortical and subcortical brain networks. These networks are systems of interconnected brain structures that work together to perform different cognitive functions, such as thinking, perceiving and controlling ...

Researchers develop test using machine learning to help predict immunotherapy response in lymphoma patients

2025-04-01

LOS ANGELES — Researchers with City of Hope, one of the largest and most advanced cancer research and treatment organizations in the United States, with its National Medical Center in Los Angeles ranked among the nation’s top 5 cancer centers by U.S. News & World Report, and MSK have created a tool that uses machine learning to assess a non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) patient’s likely response to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy before starting the treatment, according to study results published today in Nature Medicine.

CAR T cell therapy ...

New UNSW research reveals dramatically higher loss of GDP under 4°C warming

2025-04-01

New projections by the UNSW Institute for Climate Risk & Response (ICRR) reveal a 4°C rise in global temperatures would cut world GDP by around 40% by 2100 – a stark increase from previous estimates of around 11%.

The recently-published analysis fixes an oversight in the current economic model underpinning global climate policy, toppling previous carbon benchmarks.

The results support limiting global warming to 1.7 °C, which is in line with significantly faster decarbonisation goals like the Paris Agreement, and far lower than the 2.7°C supported ...

Discovery of Quina technology challenges view of ancient human development in East Asia

2025-03-31

While the Middle Paleolithic period is viewed as a dynamic time in European and African history, it is commonly considered a static period in East Asia. New research from the University of Washington challenges that perception.

Researchers discovered a complete Quina technological system — a method for making a set of tools — in the Longtan site in southwest China, which has been dated to about 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. Quina technology was found in Europe decades ago but has never before been found in East Asia.

The team published its findings March ...