(Press-News.org) WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Purdue University researchers have reproduced portions of the female breast in a tiny slide-sized model dubbed "breast on-a-chip" that will be used to test nanomedical approaches for the detection and treatment of breast cancer.

The model mimics the branching mammary duct system, where most breast cancers begin, and will serve as an "engineered organ" to study the use of nanoparticles to detect and target tumor cells within the ducts.

Sophie Lelièvre, associate professor of basic medical sciences in the School of Veterinary Medicine, and James Leary, SVM Professor of Nanomedicine and professor of basic medical sciences in the School of Veterinary Medicine and professor of biomedical engineering in the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, led the team.

"Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in most countries, and in the U.S. alone nearly 40,000 women lost their lives to it this past year," said Lelièvre, who is associate director of discovery groups in the Purdue Center for Cancer Research and a leader of the international breast cancer and nutrition project in the Oncological Sciences Center. "We've known that the best way to detect this cancer early and treat it effectively would be to get inside the mammary ducts to evaluate and treat the cells directly, and this is the first step in that direction."

Lelièvre and Leary hope eventually to be able to introduce magnetic nanoparticles through openings in the nipple, use a magnetic field to guide them through the ducts where they would attach to cancer cells and then reverse the magnetic field to retract any excess nanoparticles.

The nanoparticles could carry contrast agents to improve mammography, fluorescent markers to guide surgeons or anticancer agents to treat the cancer, Leary said.

"Nanoparticles can be designed to latch on to cancer cells and illuminate them, decreasing the size of a tumor that can be detected through mammography from 5 millimeters to 2 millimeters, which translates into finding the cancer 10 times earlier in its evolution," Leary said. "There also is great potential for nanoparticles to deliver anticancer agents directly to the cancer cells, eliminating the need for standard chemotherapy that circulates through the entire body causing harmful side effects."

Physicians have tried to access the mammary ducts through the nipple in the past, injecting fluid solutions to try to wash out cells that could be examined and used for a diagnosis of cancer. However, this approach could only reach the first third of the breast due to fluid pressure from the ducts, which branch and become smaller and smaller as they approach the glands that produce milk, Leary said.

"The idea is that nanoparticles with a magnetic core can float through the naturally occurring fluid in the ducts and be pulled by a magnet as opposed to being pushed with pressure," he said. "We think they could reach all the way to the back of the ducts, where it is believed most breast cancers originate. Of course, we are only at the earliest stages and many tests need to be done."

Such tests could not be done using standard models that grow cells across a flat surface in a plastic dish, so the team created the artificial organlike model in which living cells line a three-dimensional replica of the smallest portions of the mammary ducts.

Leary is internationally known for his nanofabrication work using photolithography to build tiny, precise structures on thin pieces of silicon to create high-speed cell sorting and analysis tools. He used the same techniques to build a mold of branching channels out of a rubberlike material called polydimethylsiloxane. The channels are about 5 millimeters long of various diameters from 20 microns to 100 microns, roughly the diameter of a human hair, that match what is found near the end of the mammary duct system.

Lelièvre, whose group is one of the few in the world able to successfully grow the complicated cells that line the mammary ducts, coaxed the cells to grow within the mold and behave as they would within a real human breast.

"The cells within the breast ductal system have a very specific organization that has proven difficult to obtain in a laboratory," Lelièvre said. "The cells have different sides, and one side must face the wall of the duct and the other must face the inner channel. Reproducing this behavior is very challenging, and it had never been achieved on an artificial structure before."

The team coated the mold in a protein-based substance called laminin 111 as a foundation for the cells that allows them to attach to the mold and behave as they would inside the body, Lelièvre said.

Because injecting the delicate cells into the finished channels of the mold caused too much damage, the team created a removable top for the channels.

"The design of the U-shaped channels and top was necessary for us to be able to successfully apply the cells, but it also allows us to make changes quickly and easily for different tests," Lelièvre said. "We can easily introduce changes among the cells or insert a few tumor cells to test the abilities of the nanoparticles to recognize them. The design also makes it very easy to evaluate the results as the entire model fits under a microscope."

A paper detailing the team's work, which was funded by the U.S. Department of Defense, is published in the current issue of Integrative Biology. In addition to Lelièvre and Leary, co-authors include graduate student Meggie Grafton, research associate Lei Wang and postdoctoral researcher Pierre-Alexandre Vidi.

The team has demonstrated that nanoparticles can be moved within the bare channels of the mold filled with fluid, but has not yet moved nanoparticles through the finished model lined with living cells, Lelièvre said.

The team next plans to create and test nanoparticles with a slippery surface that will prevent them from sticking to the cells as they travel through the channels and coatings that contain antibodies to target and attach to specific types of cancerous and precancerous cells, she said.

"Although we are at the very beginning stages of this work, we are hopeful that this nanomedical approach will one day save lives and provide patients with an easier road to recovery," Lelièvre said. "The successful creation of this model is an important milestone in this work and it is a testament to what can be accomplished through multidisciplinary research."

INFORMATION:

Lelièvre and Leary are both members of the Purdue Center for Cancer Research and the Oncological Sciences Center. Leary also is a member of the Birck Nanotechnology Center and Bindley Bioscience Center at Purdue's Discovery Park.

Writer: Elizabeth K. Gardner, 765-494-2081, ekgardner@purdue.edu

Sources: Sophie Lelièvre, 765-496-7793, lelievre@purdue.edu

James Leary, 765-494-7280, jfleary@purdue.edu

Related Web sites:

Purdue Center for Cancer Research: https://www.cancerresearch.purdue.edu/

Sophie Lelièvre: http://www.gradschool.purdue.edu/PULSe/faculty.cfm?fid=156&range=3

James Leary: http://www.purdue.edu/dp/mcf/

IMAGE CAPTION:

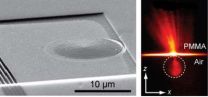

Purdue researchers' new model for breast cancer research, called "breast on-a-chip," mimics the branching mammary duct system. (Purdue University/Leary laboratory - Reproduced by permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry)

A publication-quality image is available at http://news.uns.purdue.edu/images/2011/lelievre-chip.jpg

IMAGE CAPTION:

This image shows a 3-D rendering of one of the channels lined with cells from a new model that will be used to test nanomedical approaches for the detection and treatment of breast cancer. (Purdue University/Lelièvre laboratory - reproduced by permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry)

A publication-quality image is available at http://news.uns.purdue.edu/images/2011/lelievre-chip02.jpg

Abstract for the research on this release is available at: http://www.purdue.edu/newsroom/research/2011/110120LelievreLearyBreast.html

Purdue team creates 'engineered organ' model for breast cancer research

2011-01-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Blue crab research may help Chesapeake Bay watermen improve soft shell harvest

2011-01-26

Baltimore, Md. (January 24, 2011) – A research effort designed to prevent the introduction of viruses to blue crabs in a research hatchery could end up helping Chesapeake Bay watermen improve their bottom line by reducing the number of soft shell crabs perishing before reaching the market. The findings, published in the journal Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, shows that the transmission of a crab-specific virus in diseased and dying crabs likely occurs after the pre-molt (or 'peeler') crabs are removed from the wild and placed in soft-shell production facilities.

Crab ...

Loyola physician helps develop national guidelines for osteoporosis

2011-01-26

MAYWOOD, Ill. -- The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) has released new medical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Loyola physician Pauline Camacho, MD, was part of a committee that developed the guidelines to manage this major public health issue.

These recommendations were developed to reduce the risk of osteoporosis-related fractures and improve the quality of life for patients. They explain new treatment options and suggest the use of the FRAX tool (a fracture risk assessment tool developed by the World ...

GRIN plasmonics

2011-01-26

They said it could be done and now they've done it. What's more, they did it with a GRIN. A team of researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California, Berkeley, have carried out the first experimental demonstration of GRIN – for gradient index – plasmonics, a hybrid technology that opens the door to a wide range of exotic optics, including superfast computers based on light rather than electronic signals, ultra-powerful optical microscopes able to resolve DNA molecules with visible ...

Women in Congress outperform men on some measures

2011-01-26

Congresswomen consistently outperform their male counterparts on several measures of job performance, according to a recent study by University of Chicago scholar Christopher Berry.

The research comes as the 112th Congress is sworn in this month with 89 women, the first decline in female representation since 1978. The study authors argue that because women face difficult odds in reaching Congress – women account for fewer than one in six representatives – the ones who succeed are more capable on average than their male colleagues.

Women in Congress deliver more federal ...

Legal restrictions compromise effectiveness of advance directives

2011-01-26

Current legal restrictions significantly compromise the clinical effectiveness of advance directives, according to a study by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco.

Advance directives allow patients to designate health care decision-makers and specify health care preferences for future medical needs. However, "the legal requirements and restrictions necessary to execute a legally valid directive prohibit many individuals from effectively documenting their end-of-life wishes," said lead author Lesley S. Castillo, BA, a geriatrics research assistant ...

Neurologists predict more cases of stroke, dementia, Parkinson's disease and epilepsy

2011-01-26

MAYWOOD, Ill. -- As the population ages, neurologists will be challenged by a growing population of patients with stroke, dementia, Parkinson's disease and epilepsy.

The expected increase in these and other age-related neurologic disorders is among the trends that Loyola University Health System neurologists Dr. José Biller and Dr. Michael J. Schneck describe in a January, 2011, article in the journal Frontiers in Neurology.

In the past, treatment options were limited for patients with neurological disorders. "Colloquially, the neurologist would 'diagnose and adios,'" ...

Preschool kids know what they like: Salt, sugar and fat

2011-01-26

EUGENE, Ore. -- (Jan. 25, 2011) -- A child's taste preferences begin at home and most often involve salt, sugar and fat. And, researchers say, young kids learn quickly what brands deliver the goods.

In a study of preschoolers ages 3 to 5, involving two separate experiments, researchers found that salt, sugar and fat are what kids most prefer -- and that these children already could equate their taste preferences to brand-name fast-food and soda products.

In a world where salt, sugar and fat have been repeatedly linked to obesity, waiting for children to begin school ...

Biologists' favorite worm gets viruses

2011-01-26

A workhorse of modern biology is sick, and scientists couldn't be happier.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the Jacques Monod Institute in France and Cambridge University have found that the nematode C. elegans, a millimeter-long worm used extensively for decades to study many aspects of biology, gets naturally occurring viral infections.

The discovery means C. elegans is likely to help scientists study the way viruses and their hosts interact.

"We can easily disable any of C. elegans' genes, confront the worm with a virus and ...

Possible new approach to treating a life-threatening blood disorder

2011-01-26

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a life-threatening disease of the blood system. The condition is caused by the presence of ultralarge multimers of the protein von Willebrand factor, which promote the formation of blood clots (thrombi) in small blood vessels throughout the body. Current treatments are protracted and associated with complications. However, a team of researchers, led by José López, at the Puget Sound Blood Center, Seattle, has generated data in mice that suggest that the drug N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which is FDA approved as a treatment for chronic ...

JCI table of contents: Jan. 25, 2011

2011-01-26

EDITOR'S PICK: Possible new approach to treating a life-threatening blood disorder

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a life-threatening disease of the blood system. The condition is caused by the presence of ultralarge multimers of the protein von Willebrand factor, which promote the formation of blood clots (thrombi) in small blood vessels throughout the body. Current treatments are protracted and associated with complications. However, a team of researchers, led by José López, at the Puget Sound Blood Center, Seattle, has generated data in mice that suggest ...