(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA--Glioblastoma, the most common and lethal form of brain cancer and the disease that killed Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, resists nearly all treatment efforts, even when attacked simultaneously on several fronts. One explanation can be found in the tumor cells' unexpected flexibility, discovered researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

When faced with a life-threatening oxygen shortage, glioblastoma cells can shift gears and morph into blood vessels to ensure the continued supply of nutrients, reports a team led by Inder Verma, Ph.D., in a feature article in this week's issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Their study not only explains why cancer treatments that target angiogenesis--the growth of a network of blood vessels that supplies nutrients and oxygen to cancerous tissues--routinely fail in glioblastoma, but the findings may also spur the development of drugs aimed at novel targets.

"This surprising effect of anti-angiogenic therapy with drugs such as Avastin tells us that we have to rethink glioblastoma combination therapy," says senior author Verma, a professor in the Laboratory of Genetics and holder of the Irwin and Joan Jacobs Chair in Exemplary Life Science. "Disrupting the formation of tumor blood vessels is not enough; we also have to prevent the conversion of tumor cells into blood vessels cells."

To grow beyond one to two millimeters in diameter--roughly the size of a pinhead--tumors need their own independent blood supply. To recruit new vasculature from existing blood vessels, many tumors overexpress growth factors, predominantly vascular endothelial growth factor, or VEGF. This led to the development of Avastin, a monoclonal antibody that intercepts VEGF.

"In a recent phase II clinical trial, 60 percent of patients with glioblastoma responded to a combination of Avastin and Irinotecan, which directly interferes with the growth of cancer cells," explains Verma, "but in most patients this effect was only transient." In fact, studies have shown that tumor cells often become more aggressive after anti-angiogenic therapy, but the reason had been unclear.

To find out, postdoctoral researcher and first author Yasushi Soda, Ph.D., took advantage of a mouse model of glioblastoma that recapitulates the development and progression of human brain tumors that arise naturally. "The tumors in these mice closely resemble glioblastomas, including the typically messy and highly permeable tumor vessels, which allowed us to study the tumor vasculature in great detail," he explains.

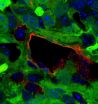

The glioblastoma mice, the concept for which was developed in the Verma laboratory, grow brain tumors within a few months of being injected with viruses that carry activated oncogenes and a marker gene that causes all tumor-derived cells to glow green under ultraviolet light. By simply tracking the green glow under the microscope, the Salk researchers can then follow the fate of tumor cells.

When Soda peered at the tumor cells, he found--much to his surprise--that about 30 percent of vascular endothelial cells--specialized cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels--appeared green. "This indicated to us that they most likely originated from tumor cells," he says.

Further experiments revealed that TDECs, short for tumor-derived endothelial cells, are not specific to mouse tumors but can also be found in clinical samples taken from human glioblastoma patients. "This was really strong evidence for us that glioblastoma cells routinely transdifferentiate into endothelial cells," he explains.

The transformation is triggered by hypoxia, or low oxygen levels, which signals tumor cells that the time has come to start their shape-shifting stunt. But unlike regular vascular endothelial cells, TDECs don't require VEGF to form functional blood vessels. "This might explain why, despite being initially successful, anti-angiogenic therapy ultimately fails in glioblastomas," says Verma.

Avastin interrupts normal blood vessels, but eventually they are replaced with tumor-derived vessels, which are now treatment-resistant. "Once again, we are confronted with the versatility of tumor cells, which allows them to survive and thrive under adverse conditions," says Verma. "But as we learn more about tumors' molecular flexibility, we will be able to design novel, tailor-made combination therapies to combat deadly brain tumors."

INFORMATION:

Researchers who also contributed to the work include Tomotoshi Marumoto, Dinorah Friedmann-Morvinski, Mie Soda, and Fei Liu at the Salk Institute; Hiroyuki Michiue in the Department of Physiology at the Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences; Sandra Pastorino and Santosh Kesari in the Department of Neurosciences, Moore's Cancer Center, at the University of California, San Diego; as well as Meng Yang and Robert M. Hoffmann at AntiCancer, Inc., San Diego.

The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, the Merieux Foundation, the Ellison Medical Foundation, Ipsen/Biomeasure, Sanofi Aventis, the H.N. and Frances C. Berger Foundation, and the James S. McDonnell Foundation.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Conversion of brain tumor cells into blood vessels thwarts treatment efforts

2011-01-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Purdue team creates 'engineered organ' model for breast cancer research

2011-01-26

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Purdue University researchers have reproduced portions of the female breast in a tiny slide-sized model dubbed "breast on-a-chip" that will be used to test nanomedical approaches for the detection and treatment of breast cancer.

The model mimics the branching mammary duct system, where most breast cancers begin, and will serve as an "engineered organ" to study the use of nanoparticles to detect and target tumor cells within the ducts.

Sophie Lelièvre, associate professor of basic medical sciences in the School of Veterinary Medicine, and ...

Blue crab research may help Chesapeake Bay watermen improve soft shell harvest

2011-01-26

Baltimore, Md. (January 24, 2011) – A research effort designed to prevent the introduction of viruses to blue crabs in a research hatchery could end up helping Chesapeake Bay watermen improve their bottom line by reducing the number of soft shell crabs perishing before reaching the market. The findings, published in the journal Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, shows that the transmission of a crab-specific virus in diseased and dying crabs likely occurs after the pre-molt (or 'peeler') crabs are removed from the wild and placed in soft-shell production facilities.

Crab ...

Loyola physician helps develop national guidelines for osteoporosis

2011-01-26

MAYWOOD, Ill. -- The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) has released new medical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Loyola physician Pauline Camacho, MD, was part of a committee that developed the guidelines to manage this major public health issue.

These recommendations were developed to reduce the risk of osteoporosis-related fractures and improve the quality of life for patients. They explain new treatment options and suggest the use of the FRAX tool (a fracture risk assessment tool developed by the World ...

GRIN plasmonics

2011-01-26

They said it could be done and now they've done it. What's more, they did it with a GRIN. A team of researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California, Berkeley, have carried out the first experimental demonstration of GRIN – for gradient index – plasmonics, a hybrid technology that opens the door to a wide range of exotic optics, including superfast computers based on light rather than electronic signals, ultra-powerful optical microscopes able to resolve DNA molecules with visible ...

Women in Congress outperform men on some measures

2011-01-26

Congresswomen consistently outperform their male counterparts on several measures of job performance, according to a recent study by University of Chicago scholar Christopher Berry.

The research comes as the 112th Congress is sworn in this month with 89 women, the first decline in female representation since 1978. The study authors argue that because women face difficult odds in reaching Congress – women account for fewer than one in six representatives – the ones who succeed are more capable on average than their male colleagues.

Women in Congress deliver more federal ...

Legal restrictions compromise effectiveness of advance directives

2011-01-26

Current legal restrictions significantly compromise the clinical effectiveness of advance directives, according to a study by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco.

Advance directives allow patients to designate health care decision-makers and specify health care preferences for future medical needs. However, "the legal requirements and restrictions necessary to execute a legally valid directive prohibit many individuals from effectively documenting their end-of-life wishes," said lead author Lesley S. Castillo, BA, a geriatrics research assistant ...

Neurologists predict more cases of stroke, dementia, Parkinson's disease and epilepsy

2011-01-26

MAYWOOD, Ill. -- As the population ages, neurologists will be challenged by a growing population of patients with stroke, dementia, Parkinson's disease and epilepsy.

The expected increase in these and other age-related neurologic disorders is among the trends that Loyola University Health System neurologists Dr. José Biller and Dr. Michael J. Schneck describe in a January, 2011, article in the journal Frontiers in Neurology.

In the past, treatment options were limited for patients with neurological disorders. "Colloquially, the neurologist would 'diagnose and adios,'" ...

Preschool kids know what they like: Salt, sugar and fat

2011-01-26

EUGENE, Ore. -- (Jan. 25, 2011) -- A child's taste preferences begin at home and most often involve salt, sugar and fat. And, researchers say, young kids learn quickly what brands deliver the goods.

In a study of preschoolers ages 3 to 5, involving two separate experiments, researchers found that salt, sugar and fat are what kids most prefer -- and that these children already could equate their taste preferences to brand-name fast-food and soda products.

In a world where salt, sugar and fat have been repeatedly linked to obesity, waiting for children to begin school ...

Biologists' favorite worm gets viruses

2011-01-26

A workhorse of modern biology is sick, and scientists couldn't be happier.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the Jacques Monod Institute in France and Cambridge University have found that the nematode C. elegans, a millimeter-long worm used extensively for decades to study many aspects of biology, gets naturally occurring viral infections.

The discovery means C. elegans is likely to help scientists study the way viruses and their hosts interact.

"We can easily disable any of C. elegans' genes, confront the worm with a virus and ...

Possible new approach to treating a life-threatening blood disorder

2011-01-26

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a life-threatening disease of the blood system. The condition is caused by the presence of ultralarge multimers of the protein von Willebrand factor, which promote the formation of blood clots (thrombi) in small blood vessels throughout the body. Current treatments are protracted and associated with complications. However, a team of researchers, led by José López, at the Puget Sound Blood Center, Seattle, has generated data in mice that suggest that the drug N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which is FDA approved as a treatment for chronic ...