(Press-News.org) MADISON — Future queen or tireless toiler? A paper wasp's destiny may lie in the antennal drumbeats of its caretaker.

While feeding their colony's larvae, a paper wasp queen and other dominant females periodically beat their antennae in a rhythmic pattern against the nest chambers, a behavior known as antennal drumming.

The drumming behavior is clearly audible even to human listeners and has been observed for decades, prompting numerous hypotheses about its purpose, says Robert Jeanne, a professor emeritus of entomology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Many have surmised that the drumming serves as a communication signal.

"It's a very conspicuous behavior. More than once I've discovered nests by hearing this behavior first," he says.

Jeanne and his colleagues have now linked antennal drumming to development of social caste in a native paper wasp, Polistes fuscatus. The new work is described in a study published in the Feb. 8 issue of Current Biology by Jeanne, UW-Madison postdoctoral researcher Sainath Suryanarayanan and John Hermanson, an engineer at the USDA Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wis.

Paper wasp colonies, like many other social insects, have distinct castes — workers, which build and maintain the nest and care for young, and gynes, which can become queens, lay eggs and establish new nests.

Both workers and gynes hatch from eggs laid by the colony's queen, but gynes develop large stores of body fat and other nutrients to help them survive winter or other harsh conditions, start a new nest, and produce eggs. Workers have very little fat, generally cannot lay eggs and die off as the weather turns cold.

"The puzzle has been how the same egg, the same genome can give rise to two such divergent phenotypes," says Suryanarayanan, who led the work as part of his doctoral studies.

Among honeybees, the key has been traced to the nutritional quality of the food fed to developing larvae: future queens receive the nutrient-rich "royal jelly," while future workers receive stored pollen and nectar. However, there is no evidence that paper wasps feed their young workers and gynes differently, he says.

Rather, the new work shows that exposure to simulated antennal drumming biases developing larvae toward the physiological characteristics of workers rather than gynes. The finding indicates that the wasps may use antennal drumming to drive developing larvae toward one caste or the other.

The researchers brought colonies into the lab and hooked up piezoelectric devices, designed by Hermanson, to the nests to produce vibrations that simulate antennal drumming. When they introduced the signal to late-season nests that would normally be producing gynes, the hatched wasps resembled workers instead, with much lower fat stores.

Suryanarayanan and Jeanne previously reported field studies that show antennal drumming is very frequent early in the season, when colonies are pumping out workers to expand and maintain the nest and take care of young. The behavior drops during the course of the season to nearly zero by late summer, the time when the reproductive wasps — males and future queens — are being reared.

"We think it initiates a biochemical signaling cascade of events," Suryanarayanan says. "Larvae who receive this drumming may express a set of genes that is different from larvae who don't, genes for proteins that relate to caste." Some possibilities might include hormones, neurotransmitters or other small biologically active molecules, he adds.

Much is known about the effects of stressors, including mechanical stress or vibrations, on animal development and physiology. Intriguingly, one study found that young mice exposed to low-frequency vibrations developed less fat and more bone mass than other mice. But the wasp's use of vibration to communicate with its own young sets it apart.

"This is the first case we know of a mechanical vibratory signal that an animal has evolved to modulate the development of members of its own species," says Jeanne.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by a National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant, and the UW-Madison Department of Zoology and College of Agricultural and Life Sciences.

— Jill Sakai, 608-262-9772, jasakai@wisc.edu

EDITOR'S NOTE: A high-resolution image and a video to accompany this story are available at: http://www.news.wisc.edu/newsphotos/social-wasps.html

CONTACT: Robert Jeanne, rljeanne@wisc.edu, 608-262-0899; Sainath Suryanarayanan, suryanas@entomology.wisc.edu, 608-698-0592

END

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) –– A new scientific study shows that debris coverage –– pebbles, rocks, and debris from surrounding mountains –– may be a missing link in the understanding of the decline of glaciers. Debris is distinct from soot and dust, according to the scientists.

Melting of glaciers in the Himalayan Mountains affects water supplies for hundreds of millions of people living in South and Central Asia. Experts have stated that global warming is a key element in the melting of glaciers worldwide.

Bodo Bookhagen, assistant professor in the Department of Geography ...

Careful dating of new dinosaur fossils and volcanic ash around them by researchers from UC Davis and UC Berkeley casts doubt on the idea that dinosaurs appeared and opportunistically replaced other animals. Instead -- at least in one South American valley -- they seem to have existed side by side and gone through similar periods of extinction.

Geologists from Argentina and the United States announced earlier this month the discovery of a new dinosaur that roamed what is now South America 230 million years ago, at the beginning of the age of the dinosaurs. The newly discovered ...

New research led by UC Davis scientists provides insight into why some body organs are more susceptible to cell death than others and could eventually lead to advances in treating or preventing heart attack or stroke.

In a paper published Jan. 21 in the journal Molecular Cell, the UC Davis team and their collaborators at the National Institutes of Health and Johns Hopkins University report that Bax, a factor known to promote cell death, is also involved in regulating the behavior of mitochondria, the structures that provide energy inside living cells.

Mitochondria constantly ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Many of the genes that allow wheat to ward off Hessian flies are no longer effective in the southeastern United States, and care should be taken to ensure that resistance genes that so far haven't been utilized in commercial wheat lines are used prudently, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture and Purdue University scientists.

An analysis of wheat lines carrying resistance genes from dozens of locations throughout the Southeast showed that some give little or no resistance to the Hessian fly, a major pest of wheat that can cause millions of ...

LA JOLLA, CA--Glioblastoma, the most common and lethal form of brain cancer and the disease that killed Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, resists nearly all treatment efforts, even when attacked simultaneously on several fronts. One explanation can be found in the tumor cells' unexpected flexibility, discovered researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

When faced with a life-threatening oxygen shortage, glioblastoma cells can shift gears and morph into blood vessels to ensure the continued supply of nutrients, reports a team led by Inder Verma, Ph.D., ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Purdue University researchers have reproduced portions of the female breast in a tiny slide-sized model dubbed "breast on-a-chip" that will be used to test nanomedical approaches for the detection and treatment of breast cancer.

The model mimics the branching mammary duct system, where most breast cancers begin, and will serve as an "engineered organ" to study the use of nanoparticles to detect and target tumor cells within the ducts.

Sophie Lelièvre, associate professor of basic medical sciences in the School of Veterinary Medicine, and ...

Baltimore, Md. (January 24, 2011) – A research effort designed to prevent the introduction of viruses to blue crabs in a research hatchery could end up helping Chesapeake Bay watermen improve their bottom line by reducing the number of soft shell crabs perishing before reaching the market. The findings, published in the journal Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, shows that the transmission of a crab-specific virus in diseased and dying crabs likely occurs after the pre-molt (or 'peeler') crabs are removed from the wild and placed in soft-shell production facilities.

Crab ...

MAYWOOD, Ill. -- The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) has released new medical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Loyola physician Pauline Camacho, MD, was part of a committee that developed the guidelines to manage this major public health issue.

These recommendations were developed to reduce the risk of osteoporosis-related fractures and improve the quality of life for patients. They explain new treatment options and suggest the use of the FRAX tool (a fracture risk assessment tool developed by the World ...

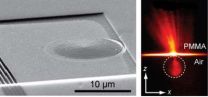

They said it could be done and now they've done it. What's more, they did it with a GRIN. A team of researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California, Berkeley, have carried out the first experimental demonstration of GRIN – for gradient index – plasmonics, a hybrid technology that opens the door to a wide range of exotic optics, including superfast computers based on light rather than electronic signals, ultra-powerful optical microscopes able to resolve DNA molecules with visible ...

Congresswomen consistently outperform their male counterparts on several measures of job performance, according to a recent study by University of Chicago scholar Christopher Berry.

The research comes as the 112th Congress is sworn in this month with 89 women, the first decline in female representation since 1978. The study authors argue that because women face difficult odds in reaching Congress – women account for fewer than one in six representatives – the ones who succeed are more capable on average than their male colleagues.

Women in Congress deliver more federal ...