(Press-News.org) Researchers have found an altogether unexpected connection between a hormone produced in bone and male fertility. The study in the February 18th issue of Cell, a Cell Press publication, shows that the skeletal hormone known as osteocalcin boosts testosterone production to support the survival of the germ cells that go on to become mature sperm.

The findings in mice provide the first evidence that the skeleton controls reproduction through the production of hormones, according to Gerard Karsenty of Columbia University and his colleagues.

Bone was once thought of as a "mere assembly of inert calcified tubes," the researchers explained. But in the last ten years, scientists have gained a much more dynamic picture of bone as a bona fide endocrine organ with links to energy metabolism and reproduction.

Prior work on skeletal ties to reproduction had focused primarily on the reproductive organs as a regulator of bone remodeling. That led Karsenty's team to wonder whether the influence might go the other way as well. Given the links between menopause and osteoporosis, his team anticipated such a connection would more likely turn up in females. But that's not what they found at all.

"We found that the bones do control reproduction, but only in males," Karsenty said. "That was obviously a surprise, but that's the finding."

Osteocalcin produced by the bone-building cells known as osteoblasts induces testosterone production by the testes, but fails to influence estrogen production by ovaries, the researchers report.

Matings between normal females and osteocalcin-deficient males produced smaller and less frequent litters than those between typical males and females. Males lacking a second gene that inhibits osteocalcin's endocrine functions showed just the opposite: larger (though not significantly larger) and more frequent litters.

The researchers further showed that osteocalcin works through a receptor found on testosterone-producing Leydig cells in the testes.

The newly identified osteocalcin receptor is already known to be expressed in human testes but not ovaries. Osteocalcin has also been shown to influence glucose metabolism in both mice and humans, suggesting that it does act as a hormone in humans.

The new discovery may lead to answers for some men who now suffer from unexplained infertility.

"Male subfertility with no apparent cause is a well-known condition," Karsenty said. He added that researchers may now begin looking for evidence that mutations in osteocalcin or its receptor might be responsible in some of those cases.

Karsenty says his team intends to continue studying the effects of bone on male fertility in greater detail, and they may yet find other links to female fertility that are independent of osteocalcin.

### END

Male fertility is in the bones

2011-02-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bears uncouple temperature and metabolism for hibernation, new study shows

2011-02-18

This release is available in French, Spanish, Arabic, Japanese and Chinese on EurekAlert! Chinese.

Several American black bears, captured by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game after wandering a bit too close to human communities, have given researchers the opportunity to study hibernation in these large mammals like never before. Surprisingly, the new findings show that although black bears only reduce their body temperatures slightly during hibernation, their metabolic activity drops dramatically, slowing to about 25 percent of their normal, active rates.

This ...

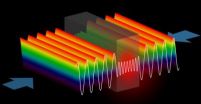

Scientists build world's first anti-laser

2011-02-18

New Haven, Conn.—More than 50 years after the invention of the laser, scientists at Yale University have built the world's first anti-laser, in which incoming beams of light interfere with one another in such a way as to perfectly cancel each other out. The discovery could pave the way for a number of novel technologies with applications in everything from optical computing to radiology.

Conventional lasers, which were first invented in 1960, use a so-called "gain medium," usually a semiconductor like gallium arsenide, to produce a focused beam of coherent light—light ...

The real avatar

2011-02-18

That feeling of being in, and owning, your own body is a fundamental human experience. But where does it originate and how does it come to be? Now, Professor Olaf Blanke, a neurologist with the Brain Mind Institute at EPFL and the Department of Neurology at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, announces an important step in decoding the phenomenon. By combining techniques from cognitive science with those of Virtual Reality (VR) and brain imaging, he and his team are narrowing in on the first experimental, data-driven approach to understanding self-consciousness.

In ...

Taking brain-computer interfaces to the next phase

2011-02-18

You may have heard of virtual keyboards controlled by thought, brain-powered wheelchairs, and neuro-prosthetic limbs. But powering these machines can be downright tiring, a fact that prevents the technology from being of much use to people with disabilities, among others. Professor José del R. Millán and his team at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland have a solution: engineer the system so that it learns about its user, allows for periods of rest, and even multitasking.

In a typical brain-computer interface (BCI) set-up, users can send ...

Skeleton regulates male fertility

2011-02-18

NEW YORK (February 17, 2011) – Researchers at Columbia University Medical Center have discovered that the skeleton acts as a regulator of fertility in male mice through a hormone released by bone, known as osteocalcin.

The research, led by Gerard Karsenty, M.D., Ph.D., chair of the Department of Genetics and Development at Columbia University Medical Center, is slated to appear online on February 17 in Cell, ahead of the journal's print edition, scheduled for March 4.

Until now, interactions between bone and the reproductive system have focused only on the influence ...

Put major government policy options through a science test first, biodiversity experts urge

2011-02-18

Scientific advice on the consequences of specific policy options confronting government decision makers is key to managing global biodiversity change.

That's the view of leading scientists anxiously anticipating the first meeting of a new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)-like mechanism for biodiversity at which its workings and work program will be defined.

Writing in the journal Science, the scientists say the new mechanism, called the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), should adopt a modified working approach ...

Subtle shifts, not major sweeps, drove human evolution

2011-02-18

The most popular model used by geneticists for the last 35 years to detect the footprints of human evolution may overlook more common subtle changes, a new international study finds.

Classic selective sweeps, when a beneficial genetic mutation quickly spreads through the human population, are thought to have been the primary driver of human evolution. But a new computational analysis, published in the February 18, 2011 issue of Science, reveals that such events may have been rare, with little influence on the history of our species.

By examining the sequences of nearly ...

Dr. Todd Kuiken, pioneer of bionic arm control at RIC, to present latest advances at AAAS meeting

2011-02-18

VIDEO:

Glen Lehman discusses his research.

Click here for more information.

WASHINGTON (February 17) –Todd Kuiken, M.D., Ph.D., Director of the Center for Bionic Medicine and Director of Amputee Services at The Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC), designated the "#1 Rehabilitation Hospital in America" by U.S. News & World Report since 1991, will present the latest in Targeted Muscle Reinnervation (TMR), a bionic limb technology, during the opening press briefing and ...

Policy experts say changes in expectations and funding key to genomic medicine's future

2011-02-18

INDIANAPOLIS – Unrealistic expectations about genomic medicine have created a "bubble" that needs deflating before it puts the field's long term benefits at risk, four policy experts write in the current issue of the journal Science.

Ten years after the deciphering of the human genetic code was accompanied by over-hyped promises of medical breakthroughs, it may be time to reevaluate funding priorities to better understand how to change behaviors and reap the health benefits that would result.

In addition, the authors say, scientists need to foster more realistic understanding ...

Scientists uncover surprising features of bear hibernation

2011-02-18

Fairbanks, ALASKA—Black bears show surprisingly large and previously unobserved decreases in their metabolism during and after hibernation according to a paper by scientists at the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and published in the 18 February issue of the journal Science.

"In general, an animal's metabolism slows to about half for each 10 degree (Celsius) drop in body temperature. Black bears' metabolism slowed by 75 percent, but their core body temperature decreased by only five to six degrees," said Øivind Tøien, IAB research scientist ...