(Press-News.org) When a bad mimic is good

Nature is full of mimics—creatures that have evolved to look or act like other more dangerous animals. However, some mimics imitate their models more convincingly than others, and new research helps explain why it sometimes pays to be a bad mimic. The research looked at three species of spider, all of which mimic, with varying degrees of accuracy, aggressive and bad-tasting ants. All of the mimics were good at avoiding being eaten by predators that target spiders, the research found. But the less accurate mimics also had a spider-like ability to evade predators that eat the model ants. "So by not looking like a spider, but also not quite looking like an ant, these inaccurate mimics have the best of both worlds, escaping both spider and ant predators," said Stano Pekár, a biologist at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic and one of the study's authors. The results show that the accuracy of mimics depends on the environment and the array of predators in the area.

Stano Pekár, Martin Jarab, Lutz Fromhage, and Marie E. Herberstein, "Is the Evolution of Inaccurate Mimicry a Result of Selection by a Suite of predators? A Case Study Using Myrmecomorphic Spiders."

You're not speaking my language: Sparrows don't respond to foreign dialects

Similar to regional dialects in human languages, bird songs often differ slightly between populations of the same species. A study led by Julie Danner of Virginia Tech shows that female rufous-collared sparrows have strong preferences for mating songs sung in a local dialect, and rarely respond sexually to foreign dialects. "The research indicates that picky females may inhibit breeding between close populations," Danner said. Such reproductive isolation could ultimately cause populations to diverge into different species. For their study, Danner and her team played recordings of several mating songs for captive females. One recording was a song from the female's local population. The other songs came from other sparrow populations, one from 15 miles away and the other from 2,500 miles away. A fourth song from a completely different bird species was also played. The research found that the females were much less likely to respond to the foreign songs. In fact, females were no more likely to respond to the song from 15 miles away than they were to the song from the other species. "Our study is the first to show tropical female mate preference for male song over a very short distance," Danner said.

Julie E. Danner, Raymond M. Danner, Frances Bonier, Paul R. Martin, Thomas W. Small, and Ignacio T. Moore, "Females, But Not Males, Respond More Strongly to the Local Song Dialect in a Tropical Sparrow: Implications for Population Divergence."

A Long-Distance Prediction for Pollinators

Is it possible to predict what kind of pollinator will visit a flower based on the flower's shape and chemistry? It is, according to a new study led by Scott Armbruster (University of Portsmouth (UK) and University of Alaska, Fairbanks). The study focused on Dalechampia, a genus of flowering vines that includes over 120 different species. After studying several Dalechampia species in South America and Africa, the researchers predicted that a previously unstudied Dalechampia species native to China would be pollinated by female resin-collecting bees around 12 to 20 millimeters in length. Armbruster and his team then conducted field observations in China to see if they were right. Sure enough, the Chinese species is pollinated by a female bee that fit the prediction. The study shows that pollination ecology can be predicted "from the pollination trends derived from studies conducted on the other side of the world," the researchers write. The finding validates the somewhat controversial idea that pollination ecology is sometimes predictable from the morphology of the flowers, Armbruster said.

W. Scott Armbruster, Yan-Bing Gong, and Shuang-Quan Huang, "Are Pollination Syndromes Predictive? Asian Dalechampia Fit Neotropical Models."

###

For the complete table of contents for the July issue, go to www.journals.uchicago.edu/an. For more information, contact Kevin Stacey at kstacey@press.uchicago.edu.

Since its inception in 1867, The American Naturalist has maintained its position as one of the world's most renowned, peer-reviewed publications in ecology, evolution, and population and integrative biology research.

News tips from the July issue of the American Naturalist

2011-06-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

EARTH: Endangered snow: How climate change threatens west coast water supplies

2011-06-21

Alexandria, VA – From Seattle to Los Angeles, anywhere from 50 to 80 percent of the water people use comes from mountain snow. Snow falls in the mountains in the winter, where it's stored as snowpack until spring and summer when it flows down the mountains into reservoirs. It's a clean, reliable source of water. But soon, it may become less dependable, thanks to climate change.

In the July feature "Endangered Snow: How climate change threatens West Coast water supplies," EARTH Magazine looks at how climate change could disrupt the balance of water and snow in the mountains, ...

Discovery of parathyroid glow promises to reduce endocrine surgery risk

2011-06-21

The parathyroid glands – four small organs the size of grains of rice located at the back of the throat – glow with a natural fluorescence in the near infrared region of the spectrum.

This unique fluorescent signature was discovered by a team of biomedical engineers and endocrine surgeons at Vanderbilt University, who have used it as the basis of a simple and reliable optical detector that can positively identify the parathyroid glands during endocrine surgery.

The report of the discovery of parathyroid fluorescence and the design of the optical detector was published ...

Panic symptoms increase steadily, not acutely, after stressful event

2011-06-21

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Just like everyone else, people with panic disorder have real stress in their lives. They get laid off and they fight with their spouses. How such stresses affect their panic symptoms hasn't been well understood, but a new study by researchers at Brown University presents the counterintuitive finding that certain kinds of stressful life events cause panic symptoms to increase gradually over succeeding months, rather than to spike immediately.

"We definitely expected the symptoms to get worse over time, but we also thought the symptoms ...

Signaling pathway is 'executive software' of airway stem cells

2011-06-21

DURHAM, NC – Researchers at Duke University Medical Center have found out how mouse basal cells that line airways "decide" to become one of two types of cells that assist in airway-clearing duties. The findings could help provide new therapies for either blocked or thinned airways.

"Our work has identified the Notch signaling pathway as a central regulatory 'switch' that controls the differentiation of airway basal stem cells," said Jason Rock, Ph.D., lead author and postdoctoral researcher in Brigid Hogan's cell biology laboratory. "Studies like ours will enhance efforts ...

Fat substitutes linked to weight gain

2011-06-21

WASHINGTON — Synthetic fat substitutes used in low-calorie potato chips and other foods could backfire and contribute to weight gain and obesity, according to a study published by the American Psychological Association.

The study, by researchers at Purdue University, challenges the conventional wisdom that foods made with fat substitutes help with weight loss. "Our research showed that fat substitutes can interfere with the body's ability to regulate food intake, which can lead to inefficient use of calories and weight gain," said Susan E. Swithers, PhD, the lead researcher ...

The myth of the 'queen bee': Work and sexism

2011-06-21

Female bosses sometimes have a reputation for not being very nice. Some display what's called "queen bee" behavior, distancing themselves from other women and refusing to help other women as they rise through the ranks. Now, a new study, which will be published in an upcoming issue of Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, concludes that it's wrong to blame the woman for this behavior; instead, blame the sexist environment.

Belle Derks of Leiden University in the Netherlands has done a lot of research on how people respond to sexism. ...

Discoveries in mitochondria open new field of cancer research

2011-06-21

Richmond, Va. (June 20, 2011) – Researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center have revealed novel mechanisms in mitochondria that have implications for cancer as well as many other age-related diseases such as Parkinson's disease, heart disease and hypertension. This discovery has pioneered the formation of a whole new field within epigenetics research ripe with possibilities of developing future gene therapies to treat cancer and age-associated diseases.

Shirley M. Taylor, Ph.D., researcher at VCU Massey Cancer Center and associate professor in ...

Northern Illinois University scientists find simple way to produce graphene

2011-06-21

DeKalb, Ill. – Scientists at Northern Illinois University say they have discovered a simple method for producing high yields of graphene, a highly touted carbon nanostructure that some believe could replace silicon as the technological fabric of the future.

The focus of intense scientific research in recent years, graphene is a two-dimensional material, comprised of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. It is the strongest material ever measured and has other remarkable qualities, including high electron mobility, a property that elevates its ...

Genius of Einstein, Fourier key to new humanlike computer vision

2011-06-21

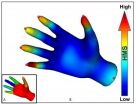

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Two new techniques for computer-vision technology mimic how humans perceive three-dimensional shapes by instantly recognizing objects no matter how they are twisted or bent, an advance that could help machines see more like people.

The techniques, called heat mapping and heat distribution, apply mathematical methods to enable machines to perceive three-dimensional objects, said Karthik Ramani, Purdue University's Donald W. Feddersen Professor of Mechanical Engineering.

"Humans can easily perceive 3-D shapes, but it's not so easy for a computer," ...

Bacteria develop restraint for survival in a rock-paper-scissors community

2011-06-21

It is a common perception that bigger, stronger, faster organisms have a distinct advantage for long-term survival when competing with other organisms in a given community.

But new research from the University of Washington shows that in some structured communities, organisms increase their chances of survival if they evolve some level of restraint that allows competitors to survive as well, a sort of "survival of the weakest."

The phenomenon was observed in a community of three "nontransitive" competitors, meaning their relationship to each other is circular as in ...