(Press-News.org) Top sirloin steaks have been getting a grilling in U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) food safety studies. USDA microbiologist John B. Luchansky and his colleagues are conducting experiments to help make sure that neither the foodborne pathogen Escherichia coli O157:H7 nor any of its pathogenic relatives will ruin the pleasure of eating this popular entrée.

The scientists are learning more about the movement of E. coli into "subprimals," the meat from which top sirloin steaks are carved. Their focus is on what happens to the E. coli when subprimals are punctured-as part of being tenderized-and the effect of cooking on survival of those microbes.

Luchansky is with USDA's Agricultural Research Service (ARS), based at the agency's Eastern Regional Research Center in Wyndmoor, Pa. ARS is the USDA's principal intramural scientific research agency.

In early studies, the researchers applied various levels of E. coli O157:H7 to the "lean-side" surface of subprimals, ran the meat (lean side up) through a blade tenderizer, and then took core samples from 10 sites on each subprimal, to a depth of about 3 inches. In general, only 3 to 4 percent of the E. coli O157:H7 cells were transported to the geometric center of the meat. At least 40 percent of the cells remained in the top 0.4 inch.

Next, the group applied E. coli to the lean-side surface of more subprimals, put the meat through a blade tenderizer, then sliced it into steaks with a thickness of three-fourths of an inch, 1 inch, or 1.25 inches. Using a commercial open-flame gas grill, they cooked the steaks-on both sides-to an internal temperature of 120 degrees Fahrenheit (very rare), 130 degrees F (rare), or 140 degrees F (medium rare).

The findings confirmed that if a relatively low level of E. coli O157:H7 is distributed throughout a blade-tenderized top sirloin steak, proper cooking on a commercial gas grill is effective for eliminating the microbe.

Luchansky conducted the studies with Wyndmoor colleagues Jeffrey E. Call, Bradley A. Shoyer, and Anna C.S. Porto-Fett; Randall K. Phebus of Kansas State University; and Harshavardhan Thippareddi of the University of Nebraska.

Published in the Journal of Food Protection in 2008 and 2009, these preliminary findings have paved the way to newer investigations. The research enhances food safety, a USDA top priority.

INFORMATION:

USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer and lender. To file a complaint of discrimination, write: USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Ave., S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice), or (202) 720-6382 (TDD).

END

Walking to the photocopier and fidgeting at your desk are contributing more to your cardiorespiratory fitness than you might think.

Researchers have found that both the duration and intensity of incidental physical activities (IPA) are associated with cardiorespiratory fitness. The intensity of the activity seems to be particularly important, with a cumulative 30-minute increase in moderate physical activity throughout the day offering significant benefits for fitness and long-term health.

"It's encouraging to know that if we just increase our incidental activity slightly--a ...

Were dinosaurs slow and lumbering, or quick and agile?

It depends largely on whether they were cold- or warm-blooded.

When dinosaurs were first discovered in the mid-19th century, paleontologists thought they were plodding beasts that relied on their environment to keep warm, like modern-day reptiles.

But research during the last few decades suggests that they were faster creatures, nimble like the velociraptors or T. rex depicted in the movie Jurassic Park, requiring warmer, regulated body temperatures.

Now, researchers, led by Robert Eagle of the California Institute ...

Doctors at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are performing a new procedure to treat atrial fibrillation, a common irregular heartbeat.

Available at only a handful of U.S. medical centers, this "hybrid" procedure combines minimally invasive surgical techniques with the latest advances in catheter ablation, a technique that applies scars to the heart's inner surface to block signals causing the heart to misfire. The two-pronged approach gives doctors access to both the inside and outside of the heart at the same time, helping to more completely block ...

MADISON, WI, JUNE 28, 2011 -- The evaluation of both nutrient and non-nutrient resource interactions provides information needed to sustainably manage agroforestry systems. Improved diagnosis of appropriate nutrient usage will help increase yields and also reduce financial and environmental costs. To achieve this, a management support system that allows for site-specific evaluation of nutrient-production imbalances is needed.

Scientists at the University of Toronto and the University of Saskatchewan have developed a conceptual framework to diagnosis nutrient and non-nutrient ...

VIDEO:

Scientists have figured out the brain mechanism that makes this optical illusion work. The illusion, known as "motion aftereffect " in scientific circles, causes us to see movement where none exist

Click here for more information.

Scientists have come up with new insight into the brain processes that cause the following optical illusion:

Focus your eyes directly on the "X" in the center of the image in this short video (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BXnUckHbPqM&feature=player_embedded)

The ...

Tiny seawater algae could hold the key to crops as a source of fuel and plants that can adapt to changing climates.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh have found that the tiny organism has developed coping mechanisms for when its main food source is in short supply.

Understanding these processes will help scientists develop crops that can survive when nutrients are scarce and to grow high-yield plants for use as biofuels.

The alga normally feeds by ingesting nitrogen from surrounding seawater but, when levels are low, it reduces its intake and instead absorbs ...

Tampa, Fla. (June 28, 2011) – Mensenchymal stem cells (MSCs), multipotent cells identified in bone marrow and other tissues, have been shown to be therapeutically effective in the immunosuppression of T-cells, the regeneration of blood vessels, assisting in skin wound healing, and suppressing chronic airway inflammation in some asthma cases. Typically, when MSCs are being prepared for therapeutic applications, they are cultured in fetal bovine serum.

A study conducted by a research team from Singapore and published in the current issue of Cell Medicine [2(1)], freely ...

In another world first, Australian Company JetBoarder pioneers the way in the new sport of JetBoarding. Their newest model, which previewed at Sanctuary Cove International Boat Show in Australia, is a real world first.

Click link to see more: http://vimeo.com/24210179

Called the 'Sprint', the focus with the kids' JetBoarder was safety first and fun second, in a new experience for kids aged 12-16. Our SPRINT Model achieves this plus more advises Chris Kanyaro. "We want to give kids the opportunity to enjoy the latest craze taking the world by storm" in ...

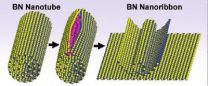

For Hollywood celebrities, the term "splitsville" usually means "check your prenup." For scientists wanting to mass-produce high quality nanoribbons from boron nitride nanotubes, "splitsville" could mean "happily ever after."

Scientists with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley, working with scientists at Rice University, have developed a technique in which boron nitride nanotubes are stuffed with atoms of potassium until the tubes split open along a longitudinal seam. This creates defect-free boron nitride ...

TORONTO, Ont., June 28, 2011—A chemical produced by the same cells that make insulin in the pancreas prevented and even reversed Type 1 diabetes in mice, researchers at St. Michael's Hospital have found.

Type 1 diabetes, formerly known as juvenile diabetes, is characterized by the immune system's destruction of the beta cells in the pancreas that make and secrete insulin. As a result, the body makes little or no insulin.

The only conventional treatment for Type 1 diabetes is insulin injection, but insulin is not a cure as it does not prevent or reverse the loss of ...