(Press-News.org) Mosquitoes die soon after a blood meal if certain protein components are experimentally disrupted, a team of biochemists at the University of Arizona has discovered.

The approach could be used as an additional strategy in the worldwide effort to curb mosquito-borne diseases like dengue fever, yellow fever and malaria.

When the researchers blocked a cellular process known as vesicle transport, on which the mosquitoes rely to release digestive enzymes into the gut among other functions, it caused the affected animals to die within two days of blood feeding.

"The idea behind our research is this: If we can kill the mosquito after she bites the first person, she won't be able to bite and infect a second," said Roger Miesfeld, a professor in the UA's department of chemistry and biochemistry, who led the research project.

"We do this by blocking the mosquito's ability to digest its blood meal," said Miesfeld, also a member of the UA's BIO5 Institute.

The research team's findings were recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, or PNAS.

"During a blood meal, a mosquito ingests its body weight in blood. It's the equivalent of a 125-pound human consuming a 12-gallon smoothie made from 25 pounds of hamburger meat plus a half pound of butter and two tablespoons of sugar," Miesfeld said.

Miesfeld and the research team had previously shown that the blood feeding process poses a huge metabolic challenge to the female mosquito.

"By disrupting any number of biochemical processes needed to fully utilize the blood meal, the mosquito has a very difficult time completing the egg production cycle," he added.

To maintain their bodily needs, the insects rely on sugary nectar from flowers, but when the time to make eggs comes, they need large amounts of protein. Only female mosquitoes bite and feed on the blood of humans or warm-blooded animals.

If a mosquito finds enough victims to bite and avoids being squashed, it can live as long as three weeks. During that time, it may lay up to five clutches of more than 100 eggs each.

For their studies, the team used mosquitoes of the species Aedes aegypti, which originally hails from the sub-tropical and tropical regions of Africa. These mosquitoes are now found in many parts of the world and are particularly abundant in towns and cities where the climate is warm and water is plentiful. A. aegypti mosquitoes buzz about at dawn and dusk in search of their next blood meal, preferably from people's ankles.

A. aegypti mosquitoes are the main vector for dengue fever, now the most common viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes. Dengue fever has made a comeback especially in subtropical and tropical regions due to the geographical spread of the mosquitoes and the virus. Four strains, or serotypes, of disease-causing dengue viruses are known.

When infected for the first time, most people suffer through a bout of high and painful fever, but usually the illness is not life threatening and renders them immune to that particular strain of dengue virus. However, a subsequent infection with any of the other dengue virus strains often triggers an all-out immune response that leads to a much more severe form, called dengue hemorrhagic fever, which can be fatal.

Miesfeld said most mosquito-borne pathogens are not passed down from the female mosquito to her offspring, but instead picked up by the mosquitoes when they bite an infected human.

In the case of A. aegypti mosquitoes, the pathogen is often dengue or yellow fever viruses, whereas the Anopheles gambiae mosquito, which is found in many parts of Africa, transmits the more deadly malaria parasite. Miesfeld further explained that malaria and dengue pathogens take about 10 to 12 days to complete their life cycle within the mosquito before they can be transmitted to humans through blood feeding.

"The most dangerous mosquitoes are the older ones," Miesfeld said.

His team used a technique called RNAi to specifically target genes that are required for the digestion process. The researchers homed in on a protein complex called COPI, which stands for coatomer protein 1.

COPI consists of several subunits that together make up the envelope of the vesicles on which the cell relies for internal transport and for secretion of enzymes into the gut.

When a female mosquito takes a blood meal, the cells lining its gut secrete enzymes to break down the blood proteins. The secretion process involves packaging the enzymes in small droplets called vesicles that the cells then release into the gut.

"We thought, 'Why don't we knock out the whole process that allows the proteases to be secreted?' That's where we got this amazing result," Miesfeld said. "Not only did we eliminate her ability to secrete anything, we were surprised to find that about 90 percent of those mosquitoes died within two days after feeding on blood."

The COPI RNAi does not have an adverse effect on the female mosquitoes for 10 days – unless they decide to take a blood meal.

"When she does, all hell starts breaking loose, biochemically and anatomically speaking," Miesfeld said.

"What we think is happening is that if there is protein in her gut, it induces the secretory machinery. It initiates this huge secretion process but it's defective and causes cells to disintegrate," he added. "The whole lining of the gut starts to fall apart, allowing the blood to seep into her body."

In looking at the potential causes, Miesfeld said his team found that removing any one of the COPI subunits causes the whole complex to fall apart.

"Based on what we know about the COPI system, it shouldn't have that strong of an effect," he said.

"As scientists have been knocking out COPI to learn more about its function over the past couple of years, they have achieved some interesting results," Miesfeld added. "Together with our findings they suggest that COPI does a lot more than what people thought."

Miesfeld envisions that the ultimate goal of this research is to develop a small molecule that works in place of injected RNAi and acts as a specific inhibitor of the secretion process.

For this to be an effective mosquito-selective insecticide, it must not have any effect on humans.

The simplest use would be to soak it into mosquito nets like currently available insecticides that target the mosquito's nervous system. A slightly more complex strategy would be to include it in a pill that humans take, so the mosquitoes pick up the inhibitor drug when they bite. As part of this strategy, the researchers are looking for genes that are unique to the mosquito and could serve as targets without affecting human health.

To explain, Miesfeld said to imagine a village in the tropics during a rainy season.

"As the mosquitoes hatch in large numbers, the whole population of villagers is ready," he explained. "As soon as the insects start biting, they take up the inhibitor and by the time they bite again, they die in large numbers. Over a few seasons, that can make a difference."

Miesfeld added it is unlikely there would ever be a silver bullet eliminating mosquito-transmitted diseases like malaria and dengue fever altogether.

"One potential issue with our strategy is genetic changes rendering the mosquitoes immune over time," Miesfeld said. "Many approaches from different angles will be necessary, and ours could be another tool in the toolbox."

INFORMATION:

You can view a related video here.

Making blood-sucking deadly for mosquitoes

Inhibiting a molecular process cells use to direct proteins to their proper destinations causes more than 90 percent of affected mosquitoes to die within 48 hours of blood feeding, a team of biochemists at the University of Arizona found

2011-07-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Rising oceans -- too late to turn the tide?

2011-07-19

Thermal expansion of seawater contributed only slightly to rising sea levels compared to melting ice sheets during the Last Interglacial Period, a University of Arizona-led team of researchers has found.

The study combined paleoclimate records with computer simulations of atmosphere-ocean interactions and the team's co-authored paper is accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters.

As the world's climate becomes warmer due to increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, sea levels are expected to rise by up to three feet by the end of this century.

But ...

NYU Langone Medical Center's tip sheet to the 2011 Alzheimer's Association International Conference

2011-07-19

NEW YORK, July 16, 2011 – Experts from the Center of Excellence on Brain Aging at NYU Langone Medical Center will present new research at the 2011 Alzheimer's Association International Conference on Alzheimer's disease to be held in Paris, France from July 16 – 21. Of particular interest is the presentation about mild cognitive impairment in retired football players, with Stella Karantzoulis, PhD, and the selected "Hot Topics" presentation about a new experimental approach to targeting amyloid plaques, with Fernando Goni, PhD. Each presentation is embargoed as noted below.

The ...

Newer techniques are making cardiac CT safer for children

2011-07-19

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) has excellent image quality and diagnostic confidence for the entire spectrum of pediatric patients, with significant reduction of risk with recent technological advancements, according to a study to be presented at the Sixth Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT) in Denver, July 14-17.

"Traditionally, pediatric patients who require coronary artery imaging have undergone a cardiac catheterization, which is an invasive procedure with a significant radiation dose, requiring sedation ...

NYU researchers develop compound to block signaling of cancer-causing protein

2011-07-19

Researchers at New York University's Department of Chemistry and NYU Langone Medical Center have developed a compound that blocks signaling from a protein implicated in many types of cancer. The compound is described in the latest issue of the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

The researchers examined signaling by receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK). Abnormal RTK signaling is a major underlying cause of various developmental disorders and diseases, including many forms of cancer. RTK signaling pathway employs interactions between proteins Sos and Ras, and accounts for a broad ...

Researchers provide means of monitoring cellular interactions

2011-07-19

Boston, MA – Using nanotechnology to engineer sensors onto the surface of cells, researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) have developed a platform technology for monitoring single-cell interactions in real-time. This innovation addresses needs in both science and medicine by providing the ability to further understand complex cell biology, track transplanted cells, and develop effective therapeutics. These findings are published in the July 17 issue of Nature Nanotechnology.

"We can now monitor how individual cells talk to one another in real-time with unprecedented ...

What keeps the Earth cooking?

2011-07-19

What spreads the sea floors and moves the continents? What melts iron in the outer core and enables the Earth's magnetic field? Heat. Geologists have used temperature measurements from more than 20,000 boreholes around the world to estimate that some 44 terawatts (44 trillion watts) of heat continually flow from Earth's interior into space. Where does it come from?

Radioactive decay of uranium, thorium, and potassium in Earth's crust and mantle is a principal source, and in 2005 scientists in the KamLAND collaboration, based in Japan, first showed that there was a way ...

'Love your body' to lose weight

2011-07-19

Almost a quarter of men and women in England and over a third of adults in America are obese. Obesity increases the risk of diabetes and heart disease and can significantly shorten a person's life expectancy. New research published by BioMed Central's open access journal International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity shows that improving body image can enhance the effectiveness of weight loss programs based on diet and exercise.

Researchers from the Technical University of Lisbon and Bangor University enrolled overweight and obese women on a year-long ...

Genetic research confirms that non-Africans are part Neanderthal

2011-07-19

Some of the human X chromosome originates from Neanderthals and is found exclusively in people outside Africa, according to an international team of researchers led by Damian Labuda of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Montreal and the CHU Sainte-Justine Research Center. The research was published in the July issue of Molecular Biology and Evolution.

"This confirms recent findings suggesting that the two populations interbred," says Dr. Labuda. His team places the timing of such intimate contacts and/or family ties early on, probably at the crossroads ...

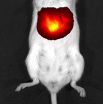

Newly developed fluorescent protein makes internal organs visible

2011-07-19

July 17, 2011 – (BRONX, NY) – Researchers at Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University have developed the first fluorescent protein that enables scientists to clearly "see" the internal organs of living animals without the need for a scalpel or imaging techniques that can have side effects or increase radiation exposure.

The new probe could prove to be a breakthrough in whole-body imaging – allowing doctors, for example, to noninvasively monitor the growth of tumors in order to assess the effectiveness of anti-cancer therapies. In contrast to other body-scanning ...

Heated AFM tip allows direct fabrication of ferroelectric nanostructures on plastic

2011-07-19

Using a technique known as thermochemical nanolithography (TCNL), researchers have developed a new way to fabricate nanometer-scale ferroelectric structures directly on flexible plastic substrates that would be unable to withstand the processing temperatures normally required to create such nanostructures.

The technique, which uses a heated atomic force microscope (AFM) tip to produce patterns, could facilitate high-density, low-cost production of complex ferroelectric structures for energy harvesting arrays, sensors and actuators in nano-electromechanical systems (NEMS) ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Predicting brain health with a smartwatch

How boron helps to produce key proteins for new cancer therapies

Writing the catalog of plasma membrane repair proteins

A comprehensive review charts how psychiatry could finally diagnose what it actually treats

Thousands of genetic variants shape epilepsy risk, and most remain hidden

First comprehensive sex-specific atlas of GLP-1 in the mouse brain reveals why blockbuster weight-loss drugs may work differently in females and males

When rats run, their gut bacteria rewrite the chemical conversation with the brain

Movies reconstructed from mouse brain activity

Subglacial weathering may have slowed Earth's escape from snowball Earth

Simple test could transform time to endometriosis diagnosis

Why ‘being squeezed’ helps breast cancer cells to thrive

Mpox immune test validated during Rwandan outbreak

Scientists pinpoint protein shapes that track Alzheimer’s progression

Researchers achieve efficient bicarbonate-mediated integrated capture and electrolysis of carbon dioxide

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

[Press-News.org] Making blood-sucking deadly for mosquitoesInhibiting a molecular process cells use to direct proteins to their proper destinations causes more than 90 percent of affected mosquitoes to die within 48 hours of blood feeding, a team of biochemists at the University of Arizona found