(Press-News.org) That cartoon scary face – wide eyes, ready to run – may have helped our primate ancestors survive in a dangerous wild, according to the authors of an article published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. The authors present a way that fear and other facial expressions might have evolved and then come to signal a person's feelings to the people around him.

The basic idea, according to Azim F. Shariff of the University of Oregon, is that the specific facial expressions associated with each particular emotion evolved for some reason. Shariff cowrote the paper with Jessica L. Tracy of the University of British Columbia. So fear helps respond to threat, and the squinched-up nose and mouth of disgust make it harder for you to inhale anything poisonous drifting on the breeze. The outthrust chest of pride increases both testosterone production and lung capacity so you're ready to take on anyone. Then, as social living became more important to the evolutionary success of certain species—most notably humans—the expressions evolved to serve a social role as well; so a happy face, for example, communicates a lack of threat and an ashamed face communicates your desire to appease.

The research is based in part on work from the last several decades showing that some emotional expressions are universal—even in remote areas with no exposure to Western media, people know what a scared face and a sad face look like, Shariff says. This type of evidence makes it unlikely that expressions were social constructs, invented in Western Europe, which then spread to the rest of the world.

And it's not just across cultures, but across species. "We seem to share a number of similar expressions, including pride, with chimpanzees and other apes," Shariff says. This suggests that the expressions appeared first in a common ancestor.

The theory that emotional facial expressions evolved as a physiological part of the response to a particular situation has been somewhat controversial in psychology; another article in the same issue of Current Directions in Psychological Science argues that the evidence on how emotions evolved is not conclusive.

Shariff and Tracy agree that more research is needed to support some of their claims, but that, "A lot of what we're proposing here would not be all that controversial to other biologists," Shariff says. "The specific concepts of 'exaptation' and 'ritualization' that we discuss are quite common when discussing the evolution of non-human animals." For example, some male birds bring a tiny morsel of food to a female bird as part of an elaborate courtship display. In that case, something that might once have been biologically relevant—sharing food with another bird—has evolved over time into a signal of his excellence as a potential mate. In the same way, Shariff says, facial expressions that started as part of the body's response to a situation may have evolved into a social signal.

###

For more information about this study, please contact: Azim Shariff at shariff@uoregon.edu.

Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, publishes concise reviews on the latest advances in theory and research spanning all of scientific psychology and its applications. For a copy of "What Are Emotion Expressions For?" and access to other Current Directions in Psychological Science research findings, please contact Lucy Hyde at 202-293-9300 or lhyde@psychologicalscience.org.

What are emotion expressions for?

2011-12-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Pions don't want to decay into faster-than-light neutrinos, study finds

2011-12-27

When an international collaboration of physicists came up with a result that punched a hole in Einstein's theory of special relativity and couldn't find any mistakes in their work, they asked the world to take a second look at their experiment.

Responding to the call was Ramanath Cowsik, PhD, professor of physics in Arts & Sciences and director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

Online and in the December 24 issue of Physical Review Letters, Cowsik and his collaborators put their finger on what appears to be an insurmountable ...

A radar for ADAR: Altered gene tracks RNA editing in neurons

2011-12-27

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — To track what they can't see, pilots look to the green glow of the radar screen. Now biologists monitoring gene expression, individual variation, and disease have a glowing green indicator of their own: Brown University biologists have developed a "radar" for tracking ADAR, a crucial enzyme for editing RNA in the nervous system.

The advance gives scientists a way to view when and where ADAR is active in a living animal and how much of it is operating. In experiments in fruit flies described in the journal Nature Methods, the researchers ...

New synthetic molecules treat autoimmune disease in mice

2011-12-27

A team of Weizmann Institute scientists has turned the tables on an autoimmune disease. In such diseases, including Crohn's and rheumatoid arthritis, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body's tissues. But the scientists managed to trick the immune systems of mice into targeting one of the body's players in autoimmune processes, an enzyme known as MMP9. The results of their research appear today in Nature Medicine.

Prof. Irit Sagi of the Biological Regulation Department and her research group have spent years looking for ways to home in on and block members of the ...

Faster, more accurate, more sensitive

2011-12-27

Lightning fast and yet highly sensitive: HHblits is a new software tool for protein research which promises to significantly improve the functional analysis of proteins. A team of computational biologists led by Dr. Johannes Söding of LMU's Genzentrum has developed a new sequence search method to identify proteins with similar sequences in databases that is faster and can discover twice as many evolutionarily related proteins as previous methods. From the functional and structural properties of the identified proteins conclusions can then be drawn on the properties of ...

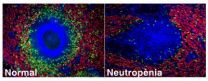

Discovered the existence of neutrophils in the spleen

2011-12-27

This release is available in Spanish.

Barcelona, 23rd of December 2011.- For the first time, it has been discovered that neutrophils exist in the spleen without there being an infection. This important finding made by the research group on the Biology of B Cells of IMIM (Hospital del Mar Research Institute) in collaboration with researchers from Mount Sinai in New York, has also made it possible to determine that these neutrophils have an immunoregulating role.

Neutrophils are the so-called cleaning cells, since they are the first cells to migrate to a place ...

Study links quality of mother-toddler relationship to teen obesity

2011-12-27

COLUMBUS, Ohio – The quality of the emotional relationship between a mother and her young child could affect the potential for that child to be obese during adolescence, a new study suggests.

Researchers analyzed national data detailing relationship characteristics between mothers and their children during their toddler years. The lower the quality of the relationship in terms of the child's emotional security and the mother's sensitivity, the higher the risk that a child would be obese at age 15 years, according to the analysis.

Among those toddlers who had the lowest-quality ...

Memo to pediatricians: Allergy tests are no magic bullets for diagnosis

2011-12-27

An advisory from two leading allergists, Robert Wood of the Johns Hopkins Children's Center and Scott Sicherer of Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York, urges clinicians to use caution when ordering allergy tests and to avoid making a diagnosis based solely on test results.

In an article, published in the January issue of Pediatrics, the researchers warn that blood tests, an increasingly popular diagnostic tool in recent years, and skin-prick testing, an older weapon in the allergist's arsenal, should never be used as standalone diagnostic strategies. These tests, Sicherer ...

Study uncovers a molecular 'maturation clock' that modulates branching architecture in tomato plants

2011-12-27

Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. – The secret to pushing tomato plants to produce more fruit might not lie in an extra dose of Miracle-Gro. Instead, new research from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) suggests that an increase in fruit yield might be achieved by manipulating a molecular timer or so-called "maturation clock" that determines the number of branches that make flowers, called inflorescences.

"We have found that a delay in this clock causes more branching to occur in the inflorescences, which in turn results in more flowers and ultimately, more fruits," says CSHL ...

Over 65 million years North American mammal evolution has tracked with climate change

2011-12-27

PROVIDENCE, R.I. -- History often seems to happen in waves – fashion and musical tastes turn over every decade and empires give way to new ones over centuries. A similar pattern characterizes the last 65 million years of natural history in North America, where a novel quantitative analysis has identified six distinct, consecutive waves of mammal species diversity, or "evolutionary faunas." What force of history determined the destiny of these groupings? The numbers say it was typically climate change.

"Although we've always known in a general way that mammals respond ...

Sunlight and bunker oil a fatal combination for Pacific herring

2011-12-27

The 2007 Cosco Busan disaster, which spilled 54,000 gallons of oil into the San Francisco Bay, had an unexpectedly lethal impact on embryonic fish, devastating a commercially and ecologically important species for nearly two years, reports a new study by the University of California, Davis, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The study, to be published the week of Dec. 26 in the early edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that even small oil spills can have a large impact on marine life, and that common chemical ...