(Press-News.org) Researchers at the University of Oviedo (Spain) have come up with a way of tagging gunpowder which allows its illegal use to be detected even after it has been detonated. Based on the addition of isotopes, the technique can also be used to track and differentiate between wild fish and those from a fish farm, such as trout and salmon.

A new method for tagging and identifying objects, substances and living beings has just been presented in this month's issue of the Analytical Chemistry journal. Its creators are scientists at the University of Oviedo who have patented the procedure for inserting chemical tags into products in a way that allows them to be unmistakably identified over time.

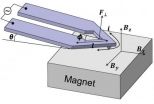

The technique consists of adding two stable (non-radioactive) isotopes (types of the same chemical element but with a different number of neutrons) at an established ratio to the object that is to be followed. Then, with an instrument called a mass spectrometer, a sample can be verified as having the predefined isotope ratio. If it does, it is therefore the tagged product.

"This technology is applicable to the invisible tagging of manufactured substances and objects such as explosives, jewellery, artwork, foods and medicines, which helps to prevent fraud and counterfeiting," explains to SINC José Ignacio García Alonso, one of its authors. "Through simple analytical techniques, a product can be traced from its origin and any possible illegal uses can be detected," he adds.

The researchers have applied this method to gunpowder, an example of an explosive, by adding two tin isotopes (Sn117 and Sn119). After preparing three different mixes (each with differing isotopic proportions so that they can be distinguished from one another), the results reveal that even after detonation the added tags can still be detected in the explosion remains.

García Alonso states that "such a procedure can be used in tagging explosives for civil or military use and can even go as far as identifying the product used in a terrorist attack."

Safe for health and the environment

The researcher also highlights that the technique can be used in living organisms without risk to health or the environment: "All living beings have these isotopes, the only thing we have done is change their ratio." Monitoring of seed dispersal or fish populations are fields of scientific research that could benefit from this technology.

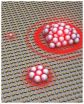

In fact, the team has successfully employed barium isotopes (Ba135 and Ba137) for tagging trout. What is more is that the injected tag in the female is transgenerational, meaning that it passes to her eggs and therefore the first generation of fry. The isotopic information is stored for life in the otoliths – a calcareous structure in the inner ears of the fish from where samples are taken.

García Alonso points out that "different tags can be injected into the trout so that the procedure can be made more specific for the descendents of a single individual or group."

The method is currently being used to assess the effectiveness of salmon repopulation in rivers in Asturias, Spain. The scientists inject one type of chemical tag into wild salmon and another type into those from a fish farm. When the fry raised in captivity are returned to the river, the efficiency of the repopulation process can be determined and river populations can be indirectly estimated.

INFORMATION:

References:

Isabel Carames-Pasaron, José Ángel Rodríguez-Castrillón, Mariella Moldovan, J. Ignacio García Alonso. "Development of a Dual-Isotope Procedure for the Tagging and Identification of Manufactured Products: Application to Explosives"; Gonzalo Huelga-Suarez, Mariella Moldovan, America Garcia-Valiente, Eva Garcia-Vázquez, J. Ignacio Garcia Alonso. "Individual-Specific Transgenerational Marking of Fish Populations Based on a Barium Dual-Isotope Procedure". Analytical Chemistry 84 (1): 121-126 y 127-133, January 2012. Doi: 10.1021/ac201945g y 10.1021/ac201946k.

Explosives and fish are traced with chemical tags

2012-01-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Discovery in Africa gives insight for Australian Hendra virus outbreaks

2012-01-13

A new study on African bats provides a vital clue for unravelling the mysteries in Australia's battle with the deadly Hendra virus.

The study focused on an isolated colony of straw-coloured fruit bats on islands off the west coast of central Africa. By capturing the bats and collecting blood samples, scientists discovered these animals have antibodies that can neutralise deadly viruses known in Australia and Asia.

The paper is published today, 12 January, in the journal PLoS ONE, and is a collaboration of the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of ...

Magnetic actuation enables nanoscale thermal analysis

2012-01-13

Polymer nano-films and nano-composites are used in a wide variety of applications from food packaging to sports equipment to automotive and aerospace applications. Thermal analysis is routinely used to analyze materials for these applications, but the growing trend to use nanostructured materials has made bulk techniques insufficient.

In recent years an atomic force microscope-based technique called nanoscale thermal analysis (nanoTA) has been employed to reveal the temperature-dependent properties of materials at the sub-100 nm scale. Typically, nanothermal analysis ...

New 'smart' nanotherapeutics can deliver drugs directly to the pancreas

2012-01-13

BOSTON, January 12, 2012: A research collaboration between the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and Children's Hospital Boston has developed "smart" injectable nanotherapeutics that can be programmed to selectively deliver drugs to the cells of the pancreas. Although this nanotechnology will need significant additional testing and development before being ready for clinical use, it could potentially improve treatment for Type I diabetes by increasing therapeutic efficacy and reducing side effects.

The approach was found to increase ...

'Open-source' robotic surgery platform going to top medical research labs

2012-01-13

SANTA CRUZ, CA--Robotics experts at the University of California, Santa Cruz and the University of Washington (UW) have completed a set of seven advanced robotic surgery systems for use by major medical research laboratories throughout the United States. After a round of final tests, five of the systems will be shipped to medical robotics researchers at Harvard University, Johns Hopkins University, University of Nebraska, UC Berkeley, and UCLA, while the other two systems will remain at UC Santa Cruz and UW.

"We decided to follow an open-source model, because if all ...

Optical nanoantennas enable efficient multipurpose particle manipulation

2012-01-13

University of Illinois researchers have shown that by tuning the properties of laser light illuminating arrays of metal nanoantennas, these nano-scale structures allow for dexterous optical tweezing as well as size-sorting of particles.

"Nanoantennas are extremely popular right now because they are really good at concentrating optical fields in small areas," explained Kimani Toussaint, Jr., an assistant professor of mechanical science and engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. "In this work, we demonstrate for the first time the use of arrays ...

Discrimination may harm your health, according to new Rice study

2012-01-13

Racial discrimination may be harmful to your health, according to new research from Rice University sociologists Jenifer Bratter and Bridget Gorman.

In the study, "Is Discrimination an Equal Opportunity Risk? Racial Experiences, Socio-economic Status and Health Status Among Black and White Adults," the authors examined data containing measures of social class, race and perceived discriminatory behavior and found that approximately 18 percent of blacks and 4 percent of whites reported higher levels of emotional upset and/or physical symptoms due to race-based treatment. ...

A scarcity of women leads men to spend more, save less

2012-01-13

The perception that women are scarce leads men to become impulsive, save less, and increase borrowing, according to new research from the University of Minnesota's Carlson School of Management.

"What we see in other animals is that when females are scarce, males become more competitive. They compete more for access to mates," says Vladas Griskevicius, an assistant professor of marketing at the Carlson School and lead author of the study. "How do humans compete for access to mates? What you find across cultures is that men often do it through money, through status and ...

Receptor for tasting fat identified in humans

2012-01-13

Why do we like fatty foods so much? We can blame our taste buds.

Our tongues apparently recognize and have an affinity for fat, according to researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. They have found that variations in a gene can make people more or less sensitive to the taste of fat.

The study is the first to identify a human receptor that can taste fat and suggests that some people may be more sensitive to the presence of fat in foods. The study is available online in the Journal of Lipid Research.

Investigators found that people with ...

Research team discovers genes and disease mechanisms behind a common form of muscular dystrophy

2012-01-13

SEATTLE – Continuing a series of groundbreaking discoveries begun in 2010 about the genetic causes of the third most common form of inherited muscular dystrophy, an international team of researchers led by a scientist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center has identified the genes and proteins that damage muscle cells, as well as the mechanisms that can cause the disease. The findings are online and will be reported in the Jan. 17 print edition of the journal Developmental Cell.

The discovery could lead to a biomarker-based test for diagnosing facioscapulohumeral muscular ...

Planets around stars are the rule rather than the exception

2012-01-13

LIVERMORE, Calif. --There are more exoplanets further away from their parent stars than originally thought, according to new astrophysics research.

In a new paper appearing in the Jan. 12 edition of the journal, Nature, astrophysicist Kem Cook as part of an international collaboration, analyzed microlensing data that bridges the gap between a recent finding of planets further away from their parent stars and observations of planets extremely close to their parent star. The results point to more planetary systems resembling our solar system rather than being significantly ...