(Press-News.org) PASADENA, Calif.—Computers, light bulbs, and even people generate heat—energy that ends up being wasted. With a thermoelectric device, which converts heat to electricity and vice versa, you can harness that otherwise wasted energy. Thermoelectric devices are touted for use in new and efficient refrigerators, and other cooling or heating machines. But present-day designs are not efficient enough for widespread commercial use or are made from rare materials that are expensive and harmful to the environment.

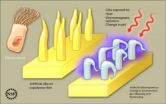

Researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have developed a new type of material—made out of silicon, the second most abundant element in Earth's crust—that could lead to more efficient thermoelectric devices. The material—a type of nanomesh—is composed of a thin film with a grid-like arrangement of tiny holes. This unique design makes it difficult for heat to travel through the material, lowering its thermal conductivity to near silicon's theoretical limit. At the same time, the design allows electricity to flow as well as it does in unmodified silicon.

"In terms of controlling thermal conductivity, these are pretty sophisticated devices," says James Heath, the Elizabeth W. Gilloon Professor and professor of chemistry at Caltech, who led the work. A paper about the research will be published in the October issue of the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

A major strategy for making thermoelectric materials energy efficient is to lower the thermal conductivity without affecting the electrical conductivity, which is how well electricity can travel through the substance. Heath and his colleagues had previously accomplished this using silicon nanowires—wires of silicon that are 10 to 100 times narrower than those currently used in computer microchips. The nanowires work by impeding heat while allowing electrons to flow freely.

In any material, heat travels via phonons—quantized packets of vibration that are akin to photons, which are themselves quantized packets of light waves. As phonons zip along the material, they deliver heat from one point to another. Nanowires, because of their tiny sizes, have a lot of surface area relative to their volume. And since phonons scatter off surfaces and interfaces, it is harder for them to make it through a nanowire without bouncing astray. As a result, a nanowire resists heat flow but remains electrically conductive.

But creating narrower and narrower nanowires is effective only up to a point. If the nanowire is too small, it will have so much relative surface area that even electrons will scatter, causing the electrical conductivity to plummet and negating the thermoelectric benefits of phonon scattering.

To get around this problem, the Caltech team built a nanomesh material from a 22-nanometer-thick sheet of silicon. (One nanometer is a billionth of a meter.) The silicon sheet is converted into a mesh—similar to a tiny window screen—with a highly regular array of 11- or 16-nanometer-wide holes that are spaced just 34 nanometers apart.

Instead of scattering the phonons traveling through it, the nanomesh changes the way those phonons behave, essentially slowing them down. The properties of a particular material determine how fast phonons can go, and it turns out that—in silicon at least—the mesh structure lowers this speed limit. As far as the phonons are concerned, the nanomesh is no longer silicon at all. "The nanomesh no longer behaves in ways typical of silicon," says Slobodan Mitrovic, a postdoctoral scholar in chemistry at Caltech. Mitrovic and Caltech graduate student Jen-Kan Yu are the first authors on the Nature Nanotechnology paper.

When the researchers compared the nanomesh to the nanowires, they found that—despite having a much higher surface-area-to-volume ratio—the nanowires were still twice as thermally conductive as the nanomesh. The researchers suggest that the decrease in thermal conductivity seen in the nanomesh is indeed caused by the slowing down of phonons, and not by phonons scattering off the mesh's surface. The team also compared the nanomesh to a thin film and to a grid-like sheet of silicon with features roughly 100 times larger than the nanomesh; both the film and the grid had thermal conductivities about 10 times higher than that of the nanomesh.

Although the electrical conductivity of the nanomesh remained comparable to regular, bulk silicon, its thermal conductivity was reduced to near the theoretical lower limit for silicon. And the researchers say they can lower it even further. "Now that we've showed that we can slow the phonons down," Heath says, "who's to say we can't slow them down a lot more?"

The researchers are now experimenting with different materials and arrangements of holes in order to optimize their design. "One day, we might be able to engineer a material where you not only can slow the phonons down, but you can exclude the phonons that carry heat altogether," Mitrovic says. "That would be the ultimate goal."

INFORMATION:

The other authors on the paper, "Reduction of thermal conductivity in phononic nanomesh structures," are Caltech graduate students Douglas Tham and Joseph Varghese. The research was funded by the Department of Energy, the Intel Foundation, a Scholar Award from the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, and the National Science Foundation.

Visit the Caltech Media Relations website at http://media.caltech.edu.

Caltech researchers design a new nanomesh material

Silicon-based film may lead to efficient thermoelectric devices

2010-09-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

University of Nevada, Reno, demonstrates successful sludge-to-power research

2010-09-24

RENO, Nev. – Like the little engine that could, the University of Nevada, Reno experiment to transform wastewater sludge to electrical power is chugging along, dwarfed by the million-gallon tanks, pipes and pumps at the Truckee Meadows Water Reclamation Facility where, ultimately, the plant's electrical power could be supplied on-site by the process University researchers are developing.

"We are very pleased with the results of the demonstration testing of our research," Chuck Coronella, principle investigator for the research project and an associate professor of chemical ...

Groundwater depletion rate accelerating worldwide

2010-09-24

WASHINGTON– In recent decades, the rate at which humans worldwide are pumping dry the vast underground stores of water that billions depend on has more than doubled, say scientists who have conducted an unusual, global assessment of groundwater use.

These fast-shrinking subterranean reservoirs are essential to daily life and agriculture in many regions, while also sustaining streams, wetlands, and ecosystems and resisting land subsidence and salt water intrusion into fresh water supplies. Today, people are drawing so much water from below that they are adding enough ...

Cilia revolution

2010-09-24

University of Southern Mississippi scientists recently imitated Mother Nature by developing, for the first time, a new, skinny-molecule-based material that resembles cilia, the tiny, hair-like structures through which organisms derive smell, vision, hearing and fluid flow.

While the new material isn't exactly like cilia, it responds to thermal, chemical, and electromagnetic stimulation, allowing researchers to control it and opening unlimited possibilities for future use.

This finding is published in today's edition of the journal Advanced Functional Materials. The ...

Taking a new look at old digs: Trampling animals may alter Stone Age sites

2010-09-24

Archaeologists who interpret Stone Age culture from discoveries of ancient tools and artifacts may need to reanalyze some of their conclusions.

That's the finding suggested by a new study that for the first time looked at the impact of water buffalo and goats trampling artifacts into mud.

In seeking to understand how much artifacts can be disturbed, the new study documented how animal trampling in a water-saturated area can result in an alarming amount of disturbance, says archaeologist Metin I. Eren, a graduate student at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, and ...

High pressure experiments reproduce mineral structures 1,800 miles deep

2010-09-24

University of California, Berkeley, and Yale University scientists have recreated the tremendous pressures and high temperatures deep in the Earth to resolve a long-standing puzzle: why some seismic waves travel faster than others through the boundary between the solid mantle and fluid outer core.

Below the earth's crust stretches an approximately 1,800-mile-thick mantle composed mostly of a mineral called magnesium silicate perovskite (MgSiO3). Below this depth, the pressures are so high that perovskite is compressed into a phase known as post-perovskite, which comprises ...

Cancer-associated long non-coding RNA regulates pre-mRNA splicing

2010-09-24

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report this month that MALAT1, a long non-coding RNA that is implicated in certain cancers, regulates pre-mRNA splicing – a critical step in the earliest stage of protein production. Their study appears in the journal Molecular Cell.

Nearly 5 percent of the human genome codes for proteins, and scientists are only beginning to understand the role of the rest of the "non-coding" genome. Among the least studied non-coding genes – which are transcribed from DNA to RNA but generally are not translated into proteins – are the long non-coding RNAs ...

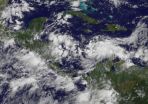

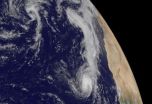

GOES-13 sees tropical depression 15 form in the south-central Caribbean Sea

2010-09-24

The fifteenth tropical depression of the Atlantic Ocean season has formed in the south-central Caribbean Sea, and the GOES-13 satellite captured its swirling mass of clouds and showers in a visible image today. Watches and warnings are already up for Central America.

At 2 p.m. EDT today, Sept. 23, Tropical Depression 15 had maximum sustained winds near 35 mph. It was located about 485 miles east of Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, near 13.9 North and 76.2 West. It was moving west at 15 mph, and had a minimum central pressure of 1007 millibars.

The government of Nicaragua ...

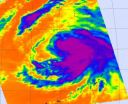

NASA sees important cloud-top temperatures as Tropical Storm Malakas heads for Iwo To

2010-09-24

NASA's Aqua satellite has peered into the cloud tops of Tropical Storm Malakas and derived just how cold they really are, giving an indication to forecasters of the strength of the storm.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder instrument, known as AIRS has the ability to determine cloud top and sea surface temperatures from its position in space aboard NASA's Aqua satellite. Cloud top temperatures help forecasters know if a storm is powering up or powering down.

When cloud top temperatures get colder it means that they're getting higher into the atmosphere which means the ...

NASA satellites help see ups and downs ahead for Depression Lisa

2010-09-24

Tropical Depression Lisa has had a struggle, and it appears that she's in for more of the same.

Infrared satellite imagery from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument on NASA's Aqua satellite shows that the convection (rapidly rising air that forms thunderstorms that make up a tropical cyclone) is increasing in Lisa. The convection is becoming a little better organized and stronger which is will make for some heavy rainfall over the northwestern Cape Verde Islands. It's also an indication that she may be strengthening back into a tropical storm today.

That ...

Team of researchers finds possible new genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease

2010-09-24

Researchers have identified a gene that appears to increase a person's risk of developing late-onset Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of the disease. The gene, abbreviated as MTHFD1L, is on chromosome six, and was identified in a genome-wide association study. Details are published September 23 in the journal PLoS Genetics.

The collaborative team of researchers was led by Margaret A. Pericak-Vance, PhD, Director of the John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine; Joseph D. Buxbaum, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Women may face heart attack risk with a lower plaque level than men

Proximity to nuclear power plants associated with increased cancer mortality

Women’s risk of major cardiac events emerges at lower coronary plaque burden compared to men

Peatland lakes in the Congo Basin release carbon that is thousands of years old

Breadcrumbs lead to fossil free production of everyday goods

New computation method for climate extremes: Researchers at the University of Graz reveal tenfold increase of heat over Europe

Does mental health affect mortality risk in adults with cancer?

EANM launches new award to accelerate alpha radioligand therapy research

Globe-trotting ancient ‘sea-salamander’ fossils rediscovered from Australia’s dawn of the Age of Dinosaurs

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

[Press-News.org] Caltech researchers design a new nanomesh materialSilicon-based film may lead to efficient thermoelectric devices