Mini-molecule governs severity of acute graft vs. host disease, study finds

2012-03-13

(Press-News.org) Graft-versus-host disease is a life-threatening problem for many bone-marrow transplant recipients.

New therapies are urgently needed to control the condition.

This study identifies a molecule that controls severity of the disease; blocking the molecule could help control the condition.

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers have identified a molecule that helps control the severity of graft-versus-host disease, a life-threatening complication for many leukemia patients who receive a bone-marrow transplant.

The study, led by researchers with the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James), used an animal model and tissues from human patients to show that high levels, or over-expression, of a molecule called microRNA-155 (miR-155) controls the severity of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Reducing or blocking miR-155 expression, on the other hand, decreased acute GVHD severity and increased survival, a finding that suggests a new strategy for treating the condition.

Acute GVHD occurs in 35 to 45 percent of leukemia patients overall who receive a blood stem-cell transplant from another person, a procedure called allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Severe acute GVHD has a poor prognosis: about 25 percent of patients survive grade III GVHD and about 5 percent survive grade IV disease.

The findings are published in the journal Blood.

"Currently, acute GVHD is treated with high doses of steroids, which further increase the patient's already high risk for infections, and they block the ability of the donor immune cells to fight the leukemia," says principal investigator and hematologist Dr. Ramiro Garzon, assistant professor of internal medicine and a leukemia specialist.

"What is needed is a way to block acute GVHD without inhibiting the ability of transplanted cells to fight leukemia, and these findings suggest how that might be done."

GVHD arises when immune cells from the donor attack the healthy tissue of the recipient. For this study, Garzon and his colleagues used an animal model of GVHD to learn if miR-155 played a role in the disease. Donor animals were engineered to either over-express or under-express miR-155 in their T cells, the main type of immune cell involved in GVHD.

The researchers first learned that donor T cells removed from recipient animals with GVHD had levels miR-155 that were up to 6.5-fold greater than in controls. Additional experiments showed the following:

When recipient animals are given T cells that are deficient in miR-155, GVHD severity is much less and overall survival is significantly greater.

When recipient animals are given T cells that over-express miR-155, GVHD develops rapidly and survival is short.

Blocking miR-155 in donor cells decreases the severity of clinical GVHD, increases survival and does not diminish the cells' ability to destroy leukemia cells.

Finally, Garzon and his colleagues examined five large-bowel biopsies of GVHD patients, and inflammatory T cells from all five showed high levels of miR-155. "This suggests that the relationship between miR-155 and graft-versus-host disease is relevant in humans, also," Garzon says.

INFORMATION:

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2012-03-13

WASHINGTON — Children may perform better in school and feel more confident about themselves if they are told that failure is a normal part of learning, rather than being pressured to succeed at all costs, according to new research published by the American Psychological Association.

"We focused on a widespread cultural belief that equates academic success with a high level of competence and failure with intellectual inferiority," said Frederique Autin, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Poitiers in Poitiers, France. "By being obsessed with success, ...

2012-03-13

BOSTON, MA—A new study by Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) researchers found significant variation in the use of head computed tomography (CT) exams among doctors within the emergency department (ED).

The study will be published in the April 2012 issue of The American Journal of Medicine.

With advanced imaging as a driver of increasing health care costs, strategies to reduce variation in head CT use and other high-cost imaging studies may reduce cost and improve quality of care. This study is part of an effort by researchers at BWH to develop strategies for achieving ...

2012-03-13

Lady@OUT is a top-up insurance product that provides female clients with a host of value-added benefits at a small additional premium.

"Even though it's a much debated and somewhat controversial topic, statistics prove that women are in fact safer and more responsible drivers than men" says Ernst Gouws, Chief Executive of OUTsurance.

"So, even though our female clients are already enjoying the benefit of lower insurance premiums, we realized that in order for us to stay ahead of the game, we'd have to think up a truly impressive product with benefits ...

2012-03-13

Beliefs about nature and nurture can affect how patients and their families respond to news about their diagnosis, according to Penn State health communication researchers.

Understanding how people might respond to a health problem, especially when the recommendations for adapting to the condition may seem contradictory to their beliefs, is crucial to planning communication strategies, said Roxanne Parrott, Distinguished Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences and Health Policy and Administration.

People affected with known genetic or chromosomal disorders, such ...

2012-03-13

Researchers at Mount Sinai School of Medicine have found that 92 percent of more than 1,000 gastroenterologists responding to a survey believed that pressures to increase the volume of colonoscopies adversely impacted how they performed their procedures, which could potentially affect the quality of colon cancer screening. The findings, based on responses from members of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), are published in the March 2012 issue of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

"The number of colonoscopies has risen dramatically over the past fifteen ...

2012-03-13

For the red pigmentation to develop, blood oranges normally require a period of cold as they ripen. The only place to reliably grow them on a commercial scale is in the Sicilian area of Italy around Mount Etna. Here, the combination of sun and cold/sunny days and warm nights provides ideal growing conditions.

Scientists have identified the gene responsible for blood orange pigmentation, naming it Ruby, and have discovered how it is controlled.

"Blood oranges contain naturally-occurring pigments associated with improved cardiovascular health, controlling diabetes and ...

2012-03-13

A recent study led by Gergely Lukacs, a professor at McGill University's Faculty of Medicine, Department of Physiology, and published in the January issue of Cell, has shown that restoring normal function to the mutant gene product responsible for cystic fibrosis (CF) requires correcting two distinct structural defects. This finding could point to more effective therapeutic strategies for CF in the future.

CF, a fatal genetic disease that affects about 60,000 people worldwide, is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a ...

2012-03-13

A novel study of honey bee genetic diversity co-authored by an Indiana University biologist has for the first time found that greater diversity in worker bees leads to colonies with fewer pathogens and more abundant helpful bacteria like probiotic species.

Led by IU Bloomington assistant professor Irene L.G. Newton and Wellesley College assistant professor Heather Mattila, and co-authors from Wellesley College and the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research, the new work describes the communities of active bacteria harbored by honey bee colonies. The ...

2012-03-13

A study of cervical cancer incidence and mortality in North Carolina has revealed areas where rates are unusually high.

The findings indicate that education, screening, and vaccination programs in those places could be particularly useful, according to public health researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who authored the report.

"In general the rates of incidence and mortality in North Carolina are consistent with national averages," said Jennifer S. Smith, Ph.D., associate professor of epidemiology at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public ...

2012-03-13

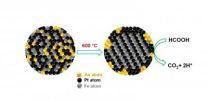

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Advances in fuel-cell technology have been stymied by the inadequacy of metals studied as catalysts. The drawback to platinum, other than cost, is that it absorbs carbon monoxide in reactions involving fuel cells powered by organic materials like formic acid. A more recently tested metal, palladium, breaks down over time.

Now chemists at Brown University have created a triple-headed metallic nanoparticle that they say outperforms and outlasts all others at the anode end in formic-acid fuel-cell reactions. In a paper published in the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Mini-molecule governs severity of acute graft vs. host disease, study finds