(Press-News.org) The Caterpillar got down off the mushroom and crawled away in the grass, remarking as it went, 'One side will make you grow taller, and the other side will make you grow shorter.'

-Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll

UCLA geneticists have identified the mutation responsible for IMAGe syndrome, a rare disorder that stunts infants' growth. The twist? The mutation occurs on the same gene that causes Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, which makes cells grow too fast, leading to very large children.

Published in the May 27 edition of Nature Genetics, the UCLA findings could lead to new ways of blocking the rapid cell division that allows tumors to grow unchecked. The discovery also offers a new tool for diagnosing children with IMAGe syndrome, which until now has been difficult to accurately identify.

The discovery holds special significance for principal investigator Dr. Eric Vilain, a professor of human genetics, pediatrics and urology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Nearly 20 years ago, as a medical resident in his native France, Vilain cared for two boys, ages 3 and 6, who were dramatically short for their ages. Though unrelated, both children shared a mysterious malady marked by minimal fetal development, stunted bone growth, sluggish adrenal glands, and undersized organs and genitals.

"I never found a reason to explain these patients' unusual set of symptoms," explained Vilain, who is also director of the UCLA Institute for Society and Genetics. "I've been searching for the cause of their disease since 1993."

When Vilain joined UCLA as a genetics fellow, the two cases continued to intrigue him. His mentor, then UCLA geneticist Dr. Edward McCabe, recalled a similar case from his previous post at Baylor College of Medicine. The two of them obtained blood samples from the three cases and analyzed the patients' DNA for mutations in suspect genes, but uncovered nothing.

Vilain and McCabe approached the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, and in 1999 published the first description of the syndrome, which they dubbed IMAGe, an acronym of sorts for the condition's symptoms: intrauterine growth restriction, metaphyseal dysplasia, adrenal hypoplasia and genital anomalies.

Over the next decade, about 20 cases were reported around the world. But the cause of IMAGe syndrome remained a mystery.

Help arrived unexpectedly last year when Vilain received an email from Argentinian physician Dr. Ignacio Bergada, who had unearthed the 1999 journal article. He told Vilain about a large family he was treating in which eight members suffered the same symptoms described in the study. All of the family members agreed to send their DNA samples to UCLA for study.

Vilain realized that he had stumbled across the scientific equivalent of winning the lottery. He assembled a team of UCLA researchers to partner with Bergada and London endocrinologist Dr. John Achermann.

"At last we had enough samples to help us zero in on the gene responsible for the syndrome," Vilain said. "Sequencing technology had also advanced in sophistication over the past two decades, allowing us to quickly analyze the entire family's DNA samples."

Vilain's team performed a linkage study, which identifies disease-related genetic markers passed down from one generation to another. The results steered Vilain to a huge swath of Chromosome 11.

The UCLA Center for Clinical Genomics performed next-generation sequencing, a powerful new technique that enabled the scientists to scour the enormous area in just two weeks and tease out a slender stretch that held the culprit mutation. The team also uncovered the same mutation in the original three cases described by Vilain in 1999.

A word of explanation: Located on 23 pairs of chromosomes, human genes hold the codes for making cellular proteins, the building blocks for our bodies. Most of the human diseases resulting from mutations in a single gene can be blamed on changes in a protein-coding sequence. By scanning the entire exome, or protein-coding factory of the genome, clinical geneticists can interpret every gene variant to track down the mutations that produce a patient's disease and rapidly reach a clear-cut diagnosis.

UCLA is one of only three academic centers in the nation that offers next-generation sequencing to the public for clinical use.

"We discovered a mutation in a tiny sliver of the chromosome that appeared in every family member affected by IMAGe syndrome," said Vilain. "This was a big step forward. Now we can use gene sequencing as a tool to screen for the disease and diagnose children early enough for them to benefit from medical intervention.

"We were a little surprised, because the mutation was located on a famous gene recognized for causing Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome," he added. "The two diseases are polar opposites of each other."

Children born with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome – named for the two doctors who discovered it – grow very large with big adrenal glands, elongated bones and oversized internal organs. Because their cells grow so fast, children with the disorder typically die of cancer at a young age. The disease affects one in 15,000 births.

"Finding opposite functions in the same gene is a rare biological phenomenon" emphasized Vilain. "When the mutation appeared in the slim section we identified, the infant developed IMAGe syndrome. If the mutation fell anywhere else in the gene, the child was born with Beckwith-Wiedemann. That's really quite remarkable."

IMAGe syndrome patients also tend to die young due to poor adrenal activity, which physicians treat with hormone-replacement therapy.

The findings proved that Vilain and his colleagues had identified the correct mutation, bringing his 20-year odyssey to a successful end.

"Our findings leave no doubt that this set of symptoms is a true syndrome and not just a figment of my imagination," said Vilain.

"What makes this special for me is finally being able to unravel what caused the life-threatening disease in the two patients I saw nearly 20 years ago," he added. "As a clinical scientist, the reward for successful research is uncovering new clues that allow us to help patients feel better by improving their medical care."

The IMAGe mutation's ability to miniaturize organisms and halt growth could offer intriguing clinical benefits, he noted.

"Our next effort will focus on manipulating the mutation's strong influence on growth to shrink tumors in the adrenal glands and other internal organs," explained Vilain.

###Vilain's coauthors included first author Valerie Arboleda, Hane Lee, Alice Fleming, Abhik Banerjee, Emmanuele Delot, Imilce Rodriguez-Fernandez, Esteban Dell'Angelica, Stanley Nelson and Julian Martinez-Agosto, all of UCLA; Bruno Ferraz-de-Souza of University of San Paulo in Brazil; Bergada of Hospital de Ninos Ricardo Gutierrez, Argentina; and Achermann of University College London Institute of Child Health.

The study was funded by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Wellcome Trust and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grants RO1HD068 and 1F31HD068136).

Same gene that stunts infants' growth also makes them grow too big

Discovery of mutation ends UCLA doctor's 20-year quest

2012-05-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

10 million years to recover from mass extinction

2012-05-28

It took some 10 million years for Earth to recover from the greatest mass extinction of all time, latest research has revealed.

Life was nearly wiped out 250 million years ago, with only 10 per cent of plants and animals surviving. It is currently much debated how life recovered from this cataclysm, whether quickly or slowly.

Recent evidence for a rapid bounce-back is evaluated in a new review article by Dr Zhong-Qiang Chen, from the China University of Geosciences in Wuhan, and Professor Michael Benton from the University of Bristol. They find that recovery from the ...

Vietnam's First Luxury Tour Operator to Open Danang Office to Tap Tourism Boom

2012-05-28

Danang has a growing range of tourist facilities which is contributing to the growth of Danang as a tourism hub. To capitalize on this trend, Luxury Travel Ltd (www.luxurytravelvietnam.com). has just opened a new Danang office to meet increased luxury tour. Luxury Travel Ltd is a long established Asian specialist in the art of travel and serves today's most sophisticated travelers, in luxury privately guided and fully bespoke holidays in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand.

Danang has stepped into the tourism limelight as a much sought after destination for ...

Yale study concludes public apathy over climate change unrelated to science literacy

2012-05-28

Are members of the public divided about climate change because they don't understand the science behind it? If Americans knew more basic science and were more proficient in technical reasoning, would public consensus match scientific consensus?

A study published today online in the journal Nature Climate Change suggests that the answer to both questions is no. Indeed, as members of the public become more science literate and numerate, the study found, individuals belonging to opposing cultural groups become even more divided on the risks that climate change poses.

Funded ...

Reed.co.uk Supports '4G Britain' Campaign

2012-05-28

One of the UKs leading job sites, www.reed.co.uk, is supporting the '4G Britain' campaign encouraging the government to invest in 4G services, pointing out that the new technology could create thousands of jobs in the UK.

The job site is advocating a recent report published by Everything Everywhere, the UKs largest network operator, which suggests 125,000 jobs could be created with sufficient investment in 4G mobile data services.

Everything Everywhere, the company formed after the merging of Orange and T-Mobile phone networks, have been strong proponents of the ...

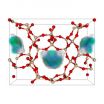

Computer model pinpoints prime materials for efficient carbon capture

2012-05-28

When power plants begin capturing their carbon emissions to reduce greenhouse gases – and to most in the electric power industry, it's a question of when, not if – it will be an expensive undertaking.

Current technologies would use about one-third of the energy generated by the plants – what's called "parasitic energy" – and, as a result, substantially drive up the price of electricity.

But a new computer model developed by University of California, Berkeley, chemists shows that less expensive technologies are on the horizon. They will use new solid materials like ...

PawnUp.com Online Pawn Shop Makes it Clear: Customer Satisfaction is Our Top Priority

2012-05-28

"Life is full of moments when a need for financial help arises unexpectedly. Some of those moments are not easy by any means. A few weeks ago my grandmother passed away, and, with the void of losing a loved one, came the responsibility of making all the final arrangements for her, in Texas," said Mr. Reynolds.

"We needed to have all funeral expenses covered fast, but it was not very easy for my family financially. After doing my fair share of research online, PawnUp.com looked like the most obvious choice to help us with the money ASAP, and definitely ...

T cells 'hunt' parasites like animal predators seek prey, a Penn Vet-Penn Physics study reveals

2012-05-28

PHILADELPHIA — By pairing an intimate knowledge of immune-system function with a deep understanding of statistical physics, a cross-disciplinary team at the University of Pennsylvania has arrived at a surprising finding: T cells use a movement strategy to track down parasites that is similar to strategies that predators such as monkeys, sharks and blue-fin tuna use to hunt their prey.

With this new insight into immune-cell movement patterns, scientists will be able to create more accurate models of immune-system function, which may, in turn, inform novel approaches ...

'Unzipped' carbon nanotubes could help energize fuel cells and batteries, Stanford scientists say

2012-05-28

Multi-walled carbon nanotubes riddled with defects and impurities on the outside could replace some of the expensive platinum catalysts used in fuel cells and metal-air batteries, according to scientists at Stanford University. Their findings are published in the May 27 online edition of the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

"Platinum is very expensive and thus impractical for large-scale commercialization," said Hongjie Dai, a professor of chemistry at Stanford and co-author of the study. "Developing a low-cost alternative has been a major research goal for several decades."

Over ...

Timing is everything

2012-05-28

At first glance, it's hard to see how a common house sparrow and a Tyrannosaurus Rex might have anything in common. After all, one is a bird that weighs less than an ounce, and the other is a dinosaur that was the size of a school bus and tipped the scales at more than eight tons.

For all their differences, though, scientists now say that two are more closely related than many believed. A new study, led by Harvard scientists, has shown that modern birds are, essentially, living dinosaurs, with skulls that are remarkably similar to those of their juvenile ancestors.

As ...

New Website launches by a group of psychologists, to council and connect with people more conveniently

2012-05-24

Psychological Affiliates, a private practice of psychologists established by Dr. Deborah O. Day in 1988, is proud to announce the launch of their new website. This new website will make it easier for Psychological Affiliates professional consultation services. "There are a growing number of families in need of comprehensive outpatient services for a wide variety of mental health issue," mentioned Dr. Deborah O. Day in an interview.

Psychological Affiliates service provide a way to professionally address a wide variety of issues such as child abuse, play therapy, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

Prevalence of over-the-counter and prescription medication use in the US

US child mental health care need, unmet needs, and difficulty accessing services

Incidental rotator cuff abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging

Sensing local fibers in pancreatic tumors, cancer cells ‘choose’ to either grow or tolerate treatment

Barriers to mental health care leave many children behind, new data cautions

Cancer and inflammation: immunologic interplay, translational advances, and clinical strategies

Bioactive polyphenolic compounds and in vitro anti-degenerative property-based pharmacological propensities of some promising germplasms of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.

AI-powered companionship: PolyU interfaculty scholar harnesses music and empathetic speech in robots to combat loneliness

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

Study finds link between sugary drinks and anxiety in young people

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

[Press-News.org] Same gene that stunts infants' growth also makes them grow too bigDiscovery of mutation ends UCLA doctor's 20-year quest