(Press-News.org) Amsterdam, NL, 19 June 2012 – In Huntington's disease, abnormally long strands of glutamine in the huntingtin (Htt) protein, called polyglutamines, cause subtle changes in cellular functions that lead to neurodegeneration and death. Studies have shown that the activation of the heat shock response, a cellular reaction to stress, doesn't work properly in Huntington's disease. In their research to understand the effects of mutant Htt on the master regulator of the heat shock response, HSF1, researchers have discovered that the targets most affected by stress are not the classic HSF1 targets, but are associated with a range of other important biological functions. Their research is published in the inaugural issue of The Journal of Huntington's Disease.

In the first genome-wide study of how polyglutamine (polyQ)-expanded Htt alters the activity of HSF1 under conditions of stress, the researchers found that under normal conditions, HSF1 function is very similar in cells carrying either wild-type (natural) or mutant Htt. Upon heat shock, much more dramatic differences emerge in the binding of HSF1. Unexpectedly, the genes no longer regulated by HSF1 were not classical HSF1 targets, such as molecular chaperones and the various genes involved in stress response. The genes that lost binding were associated with a range of other important biological functions, such as GTPase activity, cytoskeletal binding, and focal adhesion. Disorders in many of these functions have been linked to Huntington's disease in earlier studies; the current research provides a possible mechanism to explain previous observations.

Lead investigator Ernest Fraenkel, PhD, Associate Professor, Biological Engineering, MIT, explains that the impaired ability of HSF1 to respond to stress in these cells is consistent with the slow onset of Huntington's disease. Although polyQ-expanded Htt is expressed throughout the body, it primarily affects striatum and cortex relatively late in life. "An intriguing hypothesis is that polyQ-expanded Htt sensitizes the cells to various stresses, but is not sufficiently toxic on its own to cause cell death," he notes. "We have shown that polyQ Htt significantly blunts, but does not completely eliminate, the HSF1 mediated stress response. Over time, the reduced response may lead to significant damage and cell death."

The findings raise the possibility that activating HSF1 could be an effective strategy for protecting neurons from stress and damage. However, Dr. Fraenkel notes that such a strategy will have to overcome a number of barriers. "HSF1 is highly regulated, and simply increasing its expression may not increase the levels of the active form of HSF1. Also, increased HSF1 levels may raise the risk of cancer, as tumor cells depend on HSF1 activity. Further analysis of the role of HSF1 in neurodegeneration and cancer are critical to uncovering a safe and effective strategy for using HSF1 activation to treat Huntington's disease."

In another study published in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Huntington's Disease, investigators uncover a new biological marker that may be useful in screening antioxidative compounds for the treatment of Huntington's Disease. Serum 8OHdG is sign of oxidative damage to DNA, and has been shown to be elevated in patients with HD and other neurological disorders. Coenzyme Q (CoQ) is an antioxidant that may slow progression of Huntington's disease. It is also known to decrease 8OHdG levels in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. However, it was unknown whether CoQ dosing would reduce 8OHdG in humans.

Investigators administered CoQ to 14 Huntington's disease patients and 6 healthy controls for 20 weeks. Participants started on 1200 mg/day, and the dosage increased at week 8 to 3600 mg/day. CoQ levels were tested at the beginning of the study and at weeks 4, 8, 12, and 20. Four individuals with Huntington's disease reported that they were taking CoQ at the start of the study.

Baseline CoQ levels were elevated in individuals with Huntington's disease compared with health controls, even when individuals who were taking CoQ at the start of the study were excluded, the investigators found. The researchers suggest that individuals with Huntington's disease may have naturally high levels of CoQ, or some subjects may have recently discontinued CoQ, as CoQ levels can remain elevated in the system for several weeks.

Administration of CoQ led to a reduction of 8OHdG in individuals with Huntington's disease. While not significant, they found a similar reduction in healthy controls treated with CoQ, suggesting the effect of CoQ on 8OHdG may be non-specific.

"Our study supports the hypothesis that CoQ exerts antioxidant effects in patients with Huntington's disease and therefore is a treatment that warrants further study," says lead investigator Kevin M. Biglan, MD, MPH, Associate Professor, University of Rochester. "While the current data can't address the use of 8OHdG as a surrogate marker for the clinical effectiveness of antioxidants in Huntington's disease, we've established that 8OHdG can serve as a marker of the pharmacological activity of an intervention."

### END

New studies hint at possible approaches to protect those at risk for Huntington's disease

Results published in the inaugural issue of Journal of Huntington's Disease

2012-06-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Reflected infrared light unveils never-before-seen details of Renaissance paintings

2012-06-19

WASHINGTON, June 18—When restoring damaged and faded works of art, artists often employ lasers and other sophisticated imaging techniques to study intricate details, analyze pigments, and search for subtle defects not visible to the naked eye. To refine what can be seen during the restoration process even further, a team of Italian researchers has developed a new imaging tool that can capture features not otherwise detectable with the naked eye or current imaging techniques.

The system, known as Thermal Quasi-Reflectography (TQR), is able to create revealing images using ...

Carbon is key for getting algae to pump out more oil

2012-06-19

UPTON, N.Y. — Overturning two long-held misconceptions about oil production in algae, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory show that ramping up the microbes' overall metabolism by feeding them more carbon increases oil production as the organisms continue to grow. The findings — published online in the journal Plant and Cell Physiology on May 28, 2012 — may point to new ways to turn photosynthetic green algae into tiny "green factories" for producing raw materials for alternative fuels.

"We are interested in algae because they grow ...

Pediatric regime of chemotherapy proves more effective for young adults

2012-06-19

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), usually found in pediatric patients, is far more rare and deadly in adolescent and adult patients. According to the National Marrow Donor Program, child ALL patients have a higher than 80 percent remission rate, while the recovery rate for adults stands at only 40 percent.

In current practice, pediatric and young adult ALL patients undergo different treatment regimes. Children aged 0-15 years are typically given more aggressive chemotherapy, while young adults, defined as people between 16 and 39 years of age, are treated with a round ...

Key part of plants' rapid response system revealed

2012-06-19

Science has known about plant hormones since Charles Darwin experimented with plant shoots and showed that the shoots bend toward the light as long as their tips, which are secreting a growth hormone, aren't cut off.

But it is only recently that scientists have begun to put a molecular face on the biochemical systems that modulate the levels of plant hormones to defend the plant from herbivore or pathogen attack or to allow it to adjust to changes in temperature, precipitation or soil nutrients.

Now, a cross-Atlantic collaboration between scientists at Washington University ...

Peaches, plums, nectarines give obesity, diabetes slim chance

2012-06-19

COLLEGE STATION – Peaches, plums and nectarines have bioactive compounds that can potentially fight-off obesity-related diabetes and cardiovascular disease, according to new studies by Texas AgriLife Research.

The study, which will be presented at the American Chemical Society in Philadelphia next August, showed that the compounds in stone fruits could be a weapon against "metabolic syndrome," in which obesity and inflammation lead to serious health issues, according to Dr. Luis Cisneros-Zevallos, AgriLife Research food scientist.

"In recent years obesity ...

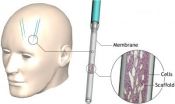

Device implanted in brain has therapeutic potential for Huntington's disease

2012-06-19

Amsterdam, NL, June 18, 2012 – Studies suggest that neurotrophic factors, which play a role in the development and survival of neurons, have significant therapeutic and restorative potential for neurologic diseases such as Huntington's disease. However, clinical applications are limited because these proteins cannot easily cross the blood brain barrier, have a short half-life, and cause serious side effects. Now, a group of scientists has successfully treated neurological symptoms in laboratory rats by implanting a device to deliver a genetically engineered neurotrophic ...

Link between vitamin C and twins can increase seed production in crops

2012-06-19

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Biochemists at the University of California, Riverside report a new role for vitamin C in plants: promoting the production of twins and even triplets in plant seeds.

Daniel R. Gallie, a professor of biochemistry, and Zhong Chen, an associate research biochemist in the Department of Biochemistry, found that increasing the level of dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), a naturally occurring enzyme that recycles vitamin C in plants and animals, increases the level of the vitamin and results in the production of twin and triplet seedlings in a single seed.

The ...

Research breakthrough: High brain integration underlies winning performances

2012-06-19

Scientists trying to understand why some people excel — whether as world-class athletes, virtuoso musicians, or top CEOs — have discovered that these outstanding performers have unique brain characteristics that make them different from other people.

A study published in May in the journal Cognitive Processing found that 20 top-level managers scored higher on three measures — the Brain Integration Scale, Gibbs's Socio-moral Reasoning questionnaire, and an inventory of peak experiences — compared to 20 low-level managers that served as matched controls. This is the fourth ...

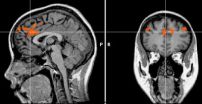

This is your brain on no self-control

2012-06-19

New pictures from the University of Iowa show what it looks like when a person runs out of patience and loses self-control.

A study by University of Iowa neuroscientist and neuro-marketing expert William Hedgcock confirms previous studies that show self-control is a finite commodity that is depleted by use. Once the pool has dried up, we're less likely to keep our cool the next time we're faced with a situation that requires self-control.

But Hedgcock's study is the first to actually show it happening in the brain using fMRI images that scan people as they perform self-control ...

Million year old groundwater in Maryland water supply

2012-06-19

A portion of the groundwater in the upper Patapsco aquifer underlying Maryland is over a million years old. A new study suggests that this ancient groundwater, a vital source of freshwater supplies for the region east of Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, was recharged over periods of time much greater than human timescales.

"Understanding the average age of groundwater allows scientists to estimate at what rate water is re-entering the aquifer to replace the water we are currently extracting for human use," explained USGS Director Marcia McNutt. "This is the first step ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

[Press-News.org] New studies hint at possible approaches to protect those at risk for Huntington's diseaseResults published in the inaugural issue of Journal of Huntington's Disease