(Press-News.org)

AUDIO:

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a potential target for treating diabetes and obesity. They discovered that when a particular protein is disabled in...

Click here for more information.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a potential target for treating diabetes and obesity.

Studying mice, they found that when the target protein was disabled, the animals became more sensitive to insulin and were less likely to get fat even when they ate a high-fat diet that caused their littermates to become obese.

The findings are published online in the journal Cell Metabolism.

The researchers studied how the body manufactures fat from dietary sources such as carbohydrates. That process requires an enzyme called fatty acid synthase (FAS). Mice engineered so that they don't make FAS in their fat cells can eat a high-fat diet without becoming obese.

"Mice without FAS were significantly more resistant to obesity than their wild-type littermates," says first author Irfan J. Lodhi, PhD. "And it wasn't because they ate less. The mice ate just as much fatty food, but they metabolized more of the fat and released it as heat."

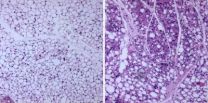

To understand why that happened, Lodhi, a research instructor in medicine, analyzed their fat cells. Mice have two types of fat: white fat and brown fat. White fat stores excess calories and contributes to obesity. Brown fat helps burn calories and protects against obesity.

In mice genetically blocked from making fatty acid synthase in fat cells, Lodhi and his colleagues noticed that the animals' white fat was transformed into tissue that resembled brown fat.

"These cells are 'brite' cells, brown fat found where white fat cells should be," Lodhi says. "They had the genetic signature of brown fat cells and acted like brown fat cells. Because the mice were resistant to obesity, it appears that fatty acid synthase may control a switch between white fat and brown fat. When we removed FAS from the equation, white fat transformed into brite cells that burned more energy."

Determining whether humans also have brown fat has been somewhat controversial throughout the years, but recent studies elsewhere have confirmed that people have it.

"It definitely exists, and perhaps the next strategy we'll use for treating people with diabetes and obesity will be to try to reverse their problems by activating these brown fat cells," says senior investigator Clay F. Semenkovich, MD.

Semenkovich, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine, professor of cell biology and physiology and director of the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Lipid Research, says the new work is exciting because FAS provides a target that may be able to activate brown fat cells to treat obesity and diabetes. But even better, he says it may be possible to target a protein downstream from FAS to lower the risk for potential side effects from the therapy.

That is possible because the scientists learned that the FAS pathway involves a family of proteins known as the PPARs (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors). PPARs are important in lipid metabolism. One of them, PPAR-alpha, helps burn fat, but the related protein, PPAR-gamma manufactures fat and helps store it.

Lodhi and Semenkovich noticed that in mice without FAS in their fat cells, activity of PPAR-alpha (the fat burner) was increased, while PPAR-gamma (the fat builder) activity decreased.

A protein called PexRAP (Peroxisomal Reductase Activating PPAR-gamma) turned out to be a downstream mediator of the effects of FAS and a key regulator of the PPAR-gamma, fat-storing pathway. When the researchers blocked PexRAP in fat cells in mice, they also interfered with the manufacture and buildup of fat.

"There was decreased fat when we blocked PexRAP," Lodhi says. "Those mice also had improved glucose metabolism, so we think that inhibiting either fatty acid synthase or PexRAP might be good strategies for treating obesity and diabetes."

Several pharmaceutical companies are working on FAS inhibitors. Meanwhile, the discovery that inhibiting PexRAP also makes the animals less obese and less diabetic has convinced the Washington University researchers to continue those studies.

"Because PexRAP is downstream, it theoretically might cause fewer side effects, but nobody knows what role the protein might play in different tissues in the body," Semenkovich says. "We need to conduct more experiments with the goal that we may be able to move into some sort of clinical trials relatively soon. It's very important to find new treatments for obesity and diabetes because these disorders aren't just an inconvenience, both can be lethal."

INFORMATION:

Lodhi IJ, Yin L, Jensen-Urstad APL, Funai K, Coleman T, Baird JH, El Ramahi MK, Razani B, Song H, Fu-Hsu F, Turk J, Semenkovich CF. Inhibiting adipose tissue lipogenesis reprograms thermogenesis and PPARγ activation to decrease diet-induced obesity. Cell Metabolism, vol. 16 (2), Aug. 8, 2012.

Funding for this research comes from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH grant numbers DK088083, DK076729, F32 DK083895, KO8 HL098550, DK20579, DK34388, RR00954 and T32 DK07120.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

New target for treating diabetes and obesity

2012-08-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Judging the role of religion in law

2012-08-03

There's a passage in the Old Testament's Deuteronomy that says if a case too difficult to decide comes before the courts, it should be brought to the Levite priests who will render a verdict in God's name. However, one University of Alberta researcher says that may be taking religious freedom a step too far.

Sarah Hamill, a doctoral student in the Faculty of Law, recently published an article in response to a premise that said judges who lack direction-setting precedence in cases should use religious-based reasoning. Hamill contends that—aside from being a serious breach ...

Deep-sea squid can 'jettison arms' as defensive tactic

2012-08-03

KINGSTON, R.I. – August 2, 2012 – A postdoctoral researcher at the University of Rhode Island has observed a never-before-seen defensive strategy used by a small species of deep-sea squid in which the animal counter-attacks a predator and then leaves the tips of its arms attached to the predator as a distraction.

Stephanie Bush said that when the foot-long octopus squid (Octopoteuthis deletron) found deep in the northeast Pacific Ocean "jettisons its arms" in self-defense, the bioluminescent tips continue to twitch and glow, creating a diversion that enables the squid ...

Vaporizing the Earth

2012-08-03

In science fiction novels, evil overlords and hostile aliens often threaten to vaporize the Earth. At the beginning of The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, the officiously bureaucratic aliens called Vogons, authors of the third-worst poetry in the universe, actually follow through on the threat, destroying the Earth to make way for a hyperspatial express route.

"We scientists are not content just to talk about vaporizing the Earth," says Bruce Fegley, professor of earth and planetary sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, tongue firmly in cheek. "We want to understand ...

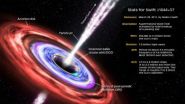

'Cry' of a shredded star heralds a new era for testing relativity

2012-08-03

Last year, astronomers discovered a quiescent black hole in a distant galaxy that erupted after shredding and consuming a passing star. Now researchers have identified a distinctive X-ray signal observed in the days following the outburst that comes from matter on the verge of falling into the black hole.

This tell-tale signal, called a quasi-periodic oscillation or QPO, is a characteristic feature of the accretion disks that often surround the most compact objects in the universe -- white dwarf stars, neutron stars and black holes. QPOs have been seen in many stellar-mass ...

Extinction risk factors for New Zealand birds today differ from those of the past

2012-08-03

Durham, NC – What makes some species more prone to extinction? A new study of nearly 300 species of New Zealand birds — from pre-human times to the present — reveals that the keys to survival today differ from those of the past.

The results are important in light of the growing number of studies that try to predict which species could be lost in the future based on what kinds of species are considered most threatened today, said lead author Lindell Bromham of Australian National University.

In the roughly 700 years since humans arrived in the remote islands that make ...

Notre Dame research into oaks helps us understand climate change

2012-08-03

Jeanne Romero-Severson, associate professor of biological sciences at the University of Notre Dame, and her collaborators, are tracking the evolution of the live oaks of eastern North America, seeking to understand how the trees adapted to climate change during glacial periods.

When the ice advanced, the oaks retreated. When the ice retreated the oaks advanced, spreading from tropical to temperate zones, up from Central America and Mexico into the Piedmont Carolinas. The researchers expect the study of live oak migrations and phylogeny will provide clues to the success ...

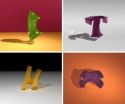

No bones about it

2012-08-03

Computer-generated characters have become so lifelike in appearance and movement that the line separating reality is almost imperceptible at times. "The Matrix" sequels messed with audiences' perceptions of reality (in more ways than one) with action scenes mixing CG characters and real actors. Almost a decade later, superheroes and alien warriors dominate the multiplex. But while bipeds and quadrupeds have reigned supreme in CG animation, attempts to create and control their skeleton-free cousins using similar techniques has proved time-consuming and laborious.

Georgia ...

Speaking multiple languages can influence children's emotional development

2012-08-03

On the classic TV show "I Love Lucy," Ricky Ricardo was known for switching into rapid-fire Spanish whenever he was upset, despite the fact Lucy had no idea what her Cuban husband was saying. These scenes were comedy gold, but they also provided a relatable portrayal of the linguistic phenomenon of code-switching.

This kind of code-switching, or switching back and forth between different languages, happens all the time in multilingual environments, and often in emotional situations. In a new article in the July issue of Perspectives on Psychological Science, a journal ...

Study shows higher healing rate using unique cell-based therapy in chronic venous leg ulcers

2012-08-03

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. -- Treating chronic venous leg ulcers with a topical spray containing a unique living human cell formula provides a 52 percent greater likelihood of wound closure than treatment with compression bandages only.

That's the conclusion of a new study conducted in part at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and published online by The Lancet this week.

The Phase II clinical trial, which investigates the efficacy of HP802-247 from Healthpoint® Biotherapeutics, was designed to determine effectiveness of certain cell concentrations and dosing ...

Mapping the future of climate change in Africa

2012-08-03

Our planet's changing climate is devastating communities in Africa through droughts, floods and myriad other disasters.

Using detailed regional climate models and geographic information systems, researchers with the Climate Change and African Political Stability (CCAPS) program developed an online mapping tool that analyzes how climate and other forces interact to threaten the security of African communities.

The program was piloted by the Robert S. Strauss Center for International Security and Law at The University of Texas at Austin in 2009 after receiving a $7.6 ...