(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA, August 9, 2012 ¬– Many of us are familiar with prion disease from its most startling and unusual incarnations—the outbreaks of "mad cow" disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy) that created a crisis in the global beef industry. Or the strange story of Kuru, a fatal illness affecting a tribe in Papua New Guinea known for its cannibalism. Both are forms of prion disease, caused by the abnormal folding of a protein and resulting in progressive neurodegeneration and death.

While exactly how the protein malfunctions has been shrouded in mystery, scientists at The Scripps Research Institute now report in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) that reducing copper in the body delays the onset of disease. Mice lacking a copper-transport gene lived significantly longer when infected with a prion disease than did normal mice.

"This conclusively shows that copper plays a role in the misfolding of the protein, but is not essential to that misfolding," said Scripps Research Professor Michael Oldstone, who led the new study.

"We've known for many years that prion proteins bind copper," said Scripps Research graduate student Owen Siggs, first author of the paper with former Oldstone lab member Justin Cruite. "But what scientists couldn't agree on was whether this was a good thing or a bad thing during prion disease. By creating a mutation in mice that lowers the amount of circulating copper by 60 percent, we've shown that reducing copper can delay the onset of prion disease."

Zombie Proteins

Unlike most infections, which are caused by bacteria, viruses, or parasites, prion disease stems from the dysfunction of a naturally occurring protein.

"We all contain a normal prion protein, and when that's converted to an abnormal prion protein, you get a chronic nervous system disease," said Oldstone. "That occurs genetically (spontaneously in some people) or is acquired by passage of infectious prions. Passage can occur by eating infected meat; in the past, by cannibalism in the Fore population in New Guinea through the ingestion or smearing of infectious brains; or by introduction of infectious prions on surgical instruments or with medical products made from infected individuals."

When introduced into the body, the abnormal prion protein causes the misfolding of other, normal prion proteins, which then aggregate into plaques in the brain and nervous system, causing tremors, agitation, and failure of motor function, and leads invariably to death.

A Delicate Balance

The role of copper in prion disease had previously been studied using chelating drugs, which strip the metals from the body—an imprecise technique. The new study, however, turned to animal models engineered in the lab of Nobel laureate Bruce Beutler while at The Scripps Research Institute. (Beutler is currently director of the Center for the Genetics of Host Defense at UT Southwestern.)

The Beutler lab had found mice with mutations disrupting copper-transporting enzyme ATP7A. The most copper-deficient mice died in utero or soon after birth, but those with milder deficiency were able to live normally.

"Copper is something we can't live without," said Siggs. "Like iron, zinc, and other metals, our bodies can't produce copper, so we absorb small amounts of it from our diet. Too little copper prevents these enzymes from working, but too much copper can also be toxic, so our body needs to maintain a fine balance. Genetic mutations like the one we describe here can disrupt this balance."

Death Delayed

In the new study, both mutant and normal mice were infected with Rocky Mountain Laboratory mouse scrapie, which causes a spongiform encephalopathy similar to mad cow disease. The control mice developed illness in about 160 days, while the mutant mice, lacking the copper-carrying gene, developed the disease later at 180 days.

Researchers also found less abnormal prion protein in the brains of mutant mice than in control mice, indicating that copper contributed to the conversion of the normal prion protein to the abnormal disease form. However, all the mice eventually died from disease.

Oldstone and Siggs note the study does not advocate for copper depletion as a therapy, at least not on its own. However, the work does pave the way for learning more about copper function in the body and the biochemical workings of prion disease.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Siggs, Cruite, Beutler, and Oldstone, authors of the paper "Disruption of copper homeostasis due to a mutation of Atp7a delays the onset of prion disease," are Xin Du formerly of Scripps Research and currently of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD); Sophie Rutschmann, formerly of Scripps Research and currently of Imperial College London; and Eliezer Masliah of UCSD. For more information, see http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2012/08/03/1211499109.abstract.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (award numbers HHSN272200700038C, AG04342, AG18440, AG022074, and NS057096) and by the General Sir John Monash Foundation.

Scripps Research Institute scientists show copper facilitates prion disease

The research provides new clue to 'mad cow' and related conditions

2012-08-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Selfish' DNA in animal mitochondria offers possible tool to study aging

2012-08-10

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Researchers at Oregon State University have discovered, for the first time in any animal species, a type of "selfish" mitochondrial DNA that is actually hurting the organism and lessening its chance to survive – and bears a strong similarity to some damage done to human cells as they age.

The findings, just published in the journal PLoS One, are a biological oddity previously unknown in animals. But they may also provide an important new tool to study human aging, scientists said.

Such selfish mitochondrial DNA has been found before in plants, but ...

Weekend hospital stays prove more deadly than other times for older people with head trauma

2012-08-10

A Johns Hopkins review of more than 38,000 patient records finds that older adults who sustain substantial head trauma over a weekend are significantly more likely to die from their injuries than those similarly hurt and hospitalized Monday through Friday, even if their injuries are less severe and they have fewer other illnesses than their weekday counterparts.

The so-called "weekend effect" on patient outcomes has been well documented in cases of heart attack, stroke and aneurism treatment, Hopkins investigators say, and the new research now affirms the problem in ...

'Theranostic' imaging offers means of killing prostate cancer cells

2012-08-10

Experimenting with human prostate cancer cells and mice, cancer imaging experts at Johns Hopkins say they have developed a method for finding and killing malignant cells while sparing healthy ones.

The method, called theranostic imaging, targets and tracks potent drug therapies directly and only to cancer cells. It relies on binding an originally inactive form of drug chemotherapy, with an enzyme, to specific proteins on tumor cell surfaces and detecting the drug's absorption into the tumor. The binding of the highly specific drug-protein complex, or nanoplex, to the ...

Rooting out rumors, epidemics, and crime -- with math

2012-08-10

Investigators are well aware of how difficult it is to trace an unlawful act to its source. The job was arguably easier with old, Mafia-style criminal organizations, as their hierarchical structures more or less resembled predictable family trees.

In the Internet age, however, the networks used by organized criminals have changed. Innumerable nodes and connections escalate the complexity of these networks, making it ever more difficult to root out the guilty party. EPFL researcher Pedro Pinto of the Audiovisual Communications Laboratory and his colleagues have developed ...

Attitudes toward outdoor smoking ban at moffitt Cancer Center evaluated

2012-08-10

Researchers at Moffitt Cancer Center who surveyed employees and patients about a ban on outdoor smoking at the cancer center found that 86 percent of non-smokers supported the ban, as did 20 percent of the employees who were smokers. Fifty-seven percent of patients who were smokers also favored the ban.

The study appeared in a recent issue of the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice.

"Policies restricting indoor worksite tobacco use have become common over the last 10 years, but smoking bans have been expanding to include outdoor smoking, with hospitals ...

Physicists explore properties of electrons in revolutionary material

2012-08-10

ATLANTA – Scientists from Georgia State University and the Georgia Institute of Technology have found a new way to examine certain properties of electrons in graphene – a very thin material that may hold the key to new technologies in computing and other fields.

Ramesh Mani, associate professor of physics at GSU, working in collaboration with Walter de Heer, Regents' Professor of physics at Georgia Tech, measured the spin properties of the electrons in graphene, a material made of carbon atoms that is only one atom thick.

The research was published this week in the ...

Thinking about giving, not receiving, motivates people to help others

2012-08-10

We're often told to 'count our blessings' and be grateful for what we have. And research shows that doing so makes us happier. But will it actually change our behavior towards others?

A new study published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, suggests that thinking about what we've given, rather than what we've received, may lead us to be more helpful toward others.

Researchers Adam Grant of The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and Jane Dutton of The Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan wanted ...

Experts issue recommendations for treating thyroid dysfunction during and after pregnancy

2012-08-10

Chevy Chase, MD—The Endocrine Society has made revisions to its 2007 Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) for management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. The CPG provides recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of patients with thyroid-related medical issues just before and during pregnancy and in the postpartum interval.

Thyroid hormone contributes critically to normal fetal brain development and having too little or too much of this hormone can impact both mother and fetus. Hypothyroid women are more likely to experience infertility and have an ...

Populations survive despite many deleterious mutations

2012-08-10

This press release is available in German.

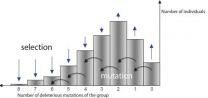

From protozoans to mammals, evolution has created more and more complex structures and better-adapted organisms. This is all the more astonishing as most genetic mutations are deleterious. Especially in small asexual populations that do not recombine their genes, unfavourable mutations can accumulate. This process is known as Muller's ratchet in evolutionary biology. The ratchet, proposed by the American geneticist Hermann Joseph Muller, predicts that the genome deteriorates irreversibly, leaving populations on a one-way street ...

New approach of resistant tuberculosis

2012-08-10

Scientists of the Antwerp Institute of Tropical Medicine have breathed new life into a forgotten technique and so succeeded in detecting resistant tuberculosis in circumstances where so far this was hardly feasible. Tuberculosis bacilli that have become resistant against our major antibiotics are a serious threat to world health.

If we do not take efficient and fast action, 'multiresistant tuberculosis' may become a worldwide epidemic, wiping out all medical achievements of the last decades.

A century ago tuberculosis was a lugubrious word, more terrifying than 'cancer' ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Evidence of a subsurface lava tube on Venus

New trial aims to transform how we track our daily diet

People are more helpful when in poor environments

How big can a planet be? With very large gas giants, it can be hard to tell

New method measures energy dissipation in the smallest devices

More than 1,000 institutions worldwide now partner with MDPI on open access

Chronic alcohol use reshapes gene expression in key human brain regions linked to relapse vulnerability and neural damage

Have associations between historical redlining and breast cancer survival changed over time?

Brief, intensive exercise helps patients with panic disorder more than standard care

How to “green” operating rooms: new guideline advises reduce, reuse, recycle, and rethink

What makes healthy boundaries – and how to implement them – according to a psychotherapist

UK’s growing synthetic opioid problem: Nitazene deaths could be underestimated by a third

How rice plants tell head from toe during early growth

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: An evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines

New global review reveals integrating finance, technology, and governance is key to equitable climate action

New study reveals cyanobacteria may help spread antibiotic resistance in estuarine ecosystems

Around the world, children’s cooperative behaviors and norms converge toward community-specific norms in middle childhood, Boston College researchers report

How cultural norms shape childhood development

University of Phoenix research finds AI-integrated coursework strengthens student learning and career skills

Next generation genetics technology developed to counter the rise of antibiotic resistance

[Press-News.org] Scripps Research Institute scientists show copper facilitates prion diseaseThe research provides new clue to 'mad cow' and related conditions