(Press-News.org) CORVALLIS, Ore. – Researchers at Oregon State University have discovered, for the first time in any animal species, a type of "selfish" mitochondrial DNA that is actually hurting the organism and lessening its chance to survive – and bears a strong similarity to some damage done to human cells as they age.

The findings, just published in the journal PLoS One, are a biological oddity previously unknown in animals. But they may also provide an important new tool to study human aging, scientists said.

Such selfish mitochondrial DNA has been found before in plants, but not animals. In this case, the discovery was made almost by accident during some genetic research being done on a nematode, Caenorhabditis briggsae – a type of small roundworm.

"We weren't even looking for this when we found it, at first we thought it must be a laboratory error," said Dee Denver, an OSU associate professor of zoology. "Selfish DNA is not supposed to be found in animals. But it could turn out to be fairly important as a new genetic model to study the type of mitochondrial decay that is associated with human aging."

DNA is the material that holds the basic genetic code for living organisms, and through complex biological processes guides beneficial cellular functions. Some of it is also found in the mitochondria, or energy-producing "powerhouse" of cells, which at one point in evolution was separate from the other DNA.

The mitochondria generally act for the benefit of the cell, even though it is somewhat separate. But the "selfish" DNA found in some plant mitochondria – and now in animals – has major differences. It tends to copy itself faster than other DNA, has no function useful to the cell, and in some cases actually harms the cell. In plants, for instance, it can affect flowering and sometimes cause sterility.

"We had seen this DNA before in this nematode and knew it was harmful, but didn't realize it was selfish," said Katie Clark, an OSU postdoctoral fellow. "Worms with it had less offspring than those without, they had less muscle activity. It might suggest that natural selection doesn't work very well in this species."

That's part of the general quandary of selfish DNA in general, the scientists said. If it doesn't help the organism survive and reproduce, why hasn't it disappeared as a result of evolutionary pressure? Its persistence, they say, is an example of how natural selection doesn't always work, either at the organism or cellular level. Biological progress is not perfect.

In this case, the population sizes of the nematode may be too small to eliminate the selfish DNA, researchers said.

What's also interesting, they say, is that the defects this selfish DNA cause in this roundworm are surprisingly similar to the decayed mitochondrial DNA that accumulates as one aspect of human aging. More of the selfish DNA is also found in the worms as they age.

Further study of these biological differences may help shed light on what can cause the mitochondrial dysfunction, Denver said, and give researchers a new tool with which to study the aging process.

### Editor's Notes: The study this story is based on is available online: http://bit.ly/OLw6YY

A digital image of this roundworm is available online: http://bit.ly/O1QohW

'Selfish' DNA in animal mitochondria offers possible tool to study aging

2012-08-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Weekend hospital stays prove more deadly than other times for older people with head trauma

2012-08-10

A Johns Hopkins review of more than 38,000 patient records finds that older adults who sustain substantial head trauma over a weekend are significantly more likely to die from their injuries than those similarly hurt and hospitalized Monday through Friday, even if their injuries are less severe and they have fewer other illnesses than their weekday counterparts.

The so-called "weekend effect" on patient outcomes has been well documented in cases of heart attack, stroke and aneurism treatment, Hopkins investigators say, and the new research now affirms the problem in ...

'Theranostic' imaging offers means of killing prostate cancer cells

2012-08-10

Experimenting with human prostate cancer cells and mice, cancer imaging experts at Johns Hopkins say they have developed a method for finding and killing malignant cells while sparing healthy ones.

The method, called theranostic imaging, targets and tracks potent drug therapies directly and only to cancer cells. It relies on binding an originally inactive form of drug chemotherapy, with an enzyme, to specific proteins on tumor cell surfaces and detecting the drug's absorption into the tumor. The binding of the highly specific drug-protein complex, or nanoplex, to the ...

Rooting out rumors, epidemics, and crime -- with math

2012-08-10

Investigators are well aware of how difficult it is to trace an unlawful act to its source. The job was arguably easier with old, Mafia-style criminal organizations, as their hierarchical structures more or less resembled predictable family trees.

In the Internet age, however, the networks used by organized criminals have changed. Innumerable nodes and connections escalate the complexity of these networks, making it ever more difficult to root out the guilty party. EPFL researcher Pedro Pinto of the Audiovisual Communications Laboratory and his colleagues have developed ...

Attitudes toward outdoor smoking ban at moffitt Cancer Center evaluated

2012-08-10

Researchers at Moffitt Cancer Center who surveyed employees and patients about a ban on outdoor smoking at the cancer center found that 86 percent of non-smokers supported the ban, as did 20 percent of the employees who were smokers. Fifty-seven percent of patients who were smokers also favored the ban.

The study appeared in a recent issue of the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice.

"Policies restricting indoor worksite tobacco use have become common over the last 10 years, but smoking bans have been expanding to include outdoor smoking, with hospitals ...

Physicists explore properties of electrons in revolutionary material

2012-08-10

ATLANTA – Scientists from Georgia State University and the Georgia Institute of Technology have found a new way to examine certain properties of electrons in graphene – a very thin material that may hold the key to new technologies in computing and other fields.

Ramesh Mani, associate professor of physics at GSU, working in collaboration with Walter de Heer, Regents' Professor of physics at Georgia Tech, measured the spin properties of the electrons in graphene, a material made of carbon atoms that is only one atom thick.

The research was published this week in the ...

Thinking about giving, not receiving, motivates people to help others

2012-08-10

We're often told to 'count our blessings' and be grateful for what we have. And research shows that doing so makes us happier. But will it actually change our behavior towards others?

A new study published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, suggests that thinking about what we've given, rather than what we've received, may lead us to be more helpful toward others.

Researchers Adam Grant of The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and Jane Dutton of The Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan wanted ...

Experts issue recommendations for treating thyroid dysfunction during and after pregnancy

2012-08-10

Chevy Chase, MD—The Endocrine Society has made revisions to its 2007 Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) for management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. The CPG provides recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of patients with thyroid-related medical issues just before and during pregnancy and in the postpartum interval.

Thyroid hormone contributes critically to normal fetal brain development and having too little or too much of this hormone can impact both mother and fetus. Hypothyroid women are more likely to experience infertility and have an ...

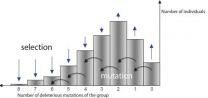

Populations survive despite many deleterious mutations

2012-08-10

This press release is available in German.

From protozoans to mammals, evolution has created more and more complex structures and better-adapted organisms. This is all the more astonishing as most genetic mutations are deleterious. Especially in small asexual populations that do not recombine their genes, unfavourable mutations can accumulate. This process is known as Muller's ratchet in evolutionary biology. The ratchet, proposed by the American geneticist Hermann Joseph Muller, predicts that the genome deteriorates irreversibly, leaving populations on a one-way street ...

New approach of resistant tuberculosis

2012-08-10

Scientists of the Antwerp Institute of Tropical Medicine have breathed new life into a forgotten technique and so succeeded in detecting resistant tuberculosis in circumstances where so far this was hardly feasible. Tuberculosis bacilli that have become resistant against our major antibiotics are a serious threat to world health.

If we do not take efficient and fast action, 'multiresistant tuberculosis' may become a worldwide epidemic, wiping out all medical achievements of the last decades.

A century ago tuberculosis was a lugubrious word, more terrifying than 'cancer' ...

How much nitrogen is fixed in the ocean?

2012-08-10

Of course scientists like it when the results of measurements fit with each other. However, when they carry out measurements in nature and compare their values, the results are rarely "smooth". A contemporary example is the ocean's nitrogen budget. Here, the question is: how much nitrogen is being fixed in the ocean and how much is released? "The answer to this question is important to predicting future climate development. All organisms need fixed nitrogen in order to build genetic material and biomass", explains Professor Julie LaRoche from the GEOMAR | Helmholtz Centre ...