(Press-News.org) Ten more DNA regions linked to type 2 diabetes have been discovered by an international team of researchers, bringing the total to over 60.

The study provides a fuller picture of the genetics and biological processes underlying type 2 diabetes, with some clear patterns emerging.

The international team, led by researchers from the University of Oxford, the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, used a new DNA chip to probe deeper into the genetic variations that commonly occur in our DNA and which may have some connection to type 2 diabetes.

Their findings are published in the journal Nature Genetics.

'The ten gene regions we have shown to be associated with type 2 diabetes are taking us nearer a biological understanding of the disease,' says principal investigator Professor Mark McCarthy of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics at the University of Oxford. 'It is hard to come up with new drugs for diabetes without first having an understanding of which biological processes in the body to target. This work is taking us closer to that goal.'

Approximately 2.9 million people are affected by diabetes in the UK, and there are thought to be perhaps a further 850,000 people with undiagnosed diabetes. Left untreated, diabetes can cause many different health problems including heart disease, stroke, nerve damage and blindness. Even a mildly raised glucose level can have damaging effects in the long-term.

Type 2 diabetes is by far the most common form of the disease. In the UK, about 90% of all adults with diabetes have type 2 diabetes. It occurs when the body does not produce enough insulin to control the level of glucose in the blood, and when the body no longer reacts effectively to the insulin that is produced.

The researchers analysed DNA from almost 35,000 people with type 2 diabetes and approximately 115,000 people without, identifying 10 new gene regions where DNA changes could be reliably linked to risk of the disease. Two of these showed different effects in men and women, one linked to greater diabetes risk in men and the other in women.

With over 60 genes and gene regions now linked to type 2 diabetes, the researchers were able to find patterns in the types of genes implicated in the disease. Although each individual gene variant has only a small influence on people's overall risk of diabetes, the types of genes involved are giving new insight into the biology behind diabetes.

Professor Mark McCarthy says: 'By looking at all 60 or so gene regions together we can look for signatures of the type of genes that influence the risk of type 2 diabetes.

'We see genes involved in controlling the process of cell growth, division and ageing, particularly those that are active in the pancreas where insulin is produced. We see genes involved in pathways through which the body's fat cells can influence biological processes elsewhere in the body. And we see a set of transcription factor genes – genes that help control what other genes are active.'

While gene association studies have been successful in finding DNA regions that can be reliably linked to type 2 diabetes, it can be hard to tie down which gene and what exact DNA change is responsible.

Professor McCarthy and colleagues' next step is to get complete information about genetic changes driving type 2 diabetes by sequencing people's DNA in full.

He is currently leading a study from Oxford University that, with collaborators in the US and Europe, has sequenced the entire genomes of 1400 people with diabetes and 1400 people without. First results will be available next year.

'Now we have the ability to do a complete job, capturing all genetic variation linked to type 2 diabetes,' says Professor McCarthy, a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator. 'Not only will we be able to look for signals we've so far missed, but we will also be able to pinpoint which individual DNA change is responsible. These genome sequencing studies will really help us push forward towards a more complete biological understanding of diabetes.'

###

Notes to editors

*It is possible to see how some types of genes identified in these studies could be involved in type 2 diabetes.

For example, one feature of type 2 diabetes is that the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas can no longer produce enough of the hormone to control glucose levels in the blood. However, it is not known whether this is because there are fewer cells left to respond to the demand, or there are plenty of cells but they don't respond as much, or both. Cell cycle genes, which control the growth, development and death of cells, could well play a role here.

Obesity is known to be a major risk factor for diabetes. Becoming obese tends to result in the body becoming less responsive to the insulin it produces. While fat must be important in this, it is the liver and muscle where the insulin resistance has an effect. The involvement of processes where fat cells communicate with other parts of the body, as suggested by the genetics findings, could explain how this occurs.

* The researchers show that the data emerging from gene association studies is consistent with the genetic contribution to diabetes being made up of many, many common gene variants each having a small effect. This is more likely than there being a significant contribution from unknown rare genetic variants that only a few people have, but which confer a much greater risk of diabetes.

Professor McCarthy says: 'We now have strong evidence that there is a long tail of further common gene variations beyond those we have identified so far. The 60 or so we know about will be the gene variants with strongest effects on risk of type 2 diabetes. But there are likely to be tens, hundreds, possibly even thousands more genes having smaller and smaller influences on development of the condition.'

* The paper 'Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes' is to be published in the journal Nature Genetics with an embargo of 13:00 US Eastern Time on Sunday 12 August 2012.

* The study was carried out by a very large international team of researchers from institutions across Europe, North America, Australia, Singapore and Pakistan. Funding came from many sources. The main funders for the Oxford University researchers were the Wellcome Trust, European Union, the National Institutes of Health in the USA, and the UK Medical Research Council.

* Oxford University's Medical Sciences Division is one of the largest biomedical research centres in Europe, with over 2,500 people involved in research and more than 2,800 students. The University is rated the best in the world for medicine, and it is home to the UK's top-ranked medical school.

From the genetic and molecular basis of disease to the latest advances in neuroscience, Oxford is at the forefront of medical research. It has one of the largest clinical trial portfolios in the UK and great expertise in taking discoveries from the lab into the clinic. Partnerships with the local NHS Trusts enable patients to benefit from close links between medical research and healthcare delivery.

A great strength of Oxford medicine is its long-standing network of clinical research units in Asia and Africa, enabling world-leading research on the most pressing global health challenges such as malaria, TB, HIV/AIDS and flu. Oxford is also renowned for its large-scale studies which examine the role of factors such as smoking, alcohol and diet on cancer, heart disease and other conditions.

* The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. It supports the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. The Trust's breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. It is independent of both political and commercial interests.

10 new diabetes gene links offer picture of biology underlying disease

2012-08-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Yale team discovers how stress and depression can shrink the brain

2012-08-13

Major depression or chronic stress can cause the loss of brain volume, a condition that contributes to both emotional and cognitive impairment. Now a team of researchers led by Yale scientists has discovered one reason why this occurs — a single genetic switch that triggers loss of brain connections in humans and depression in animal models.

The findings, reported in the Aug. 12 issue of the journal Nature Medicine, show that the genetic switch known as a transcription factor represses the expression of several genes that are necessary for the formation of synaptic connections ...

Metabolic MAGIC

2012-08-13

Researchers have identified 38 new genetic regions that are associated with glucose and insulin levels in the blood. This brings the total number of genetic regions associated with glucose and insulin levels to 53, over half of which are associated with type 2 diabetes.

The researchers used a technology that is 100 times more powerful than previous techniques used to follow-up on genome-wide association results. This technology, Metabochip, was designed as a cost-effective way to find and map genomic regions for a range of cardiovascular and metabolic characteristics ...

World's most powerful X-ray laser beam refined to scalpel precision

2012-08-13

With a thin sliver of diamond, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have transformed the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) into an even more precise tool for exploring the nanoworld. The improvements yield laser pulses focused to higher intensity in a much narrower band of X-ray wavelengths, and may enable experiments that have never before been possible.

In a process called "self-seeding," the diamond filters the laser beam to a single X-ray color, which is then amplified. Like trading a hatchet for a scalpel, the ...

Mutations disrupt cellular recycling and cause a childhood genetic disease

2012-08-13

Genetics researchers have identified a key gene that, when mutated, causes the rare multisystem disorder Cornelia deLange syndrome (CdLS). By revealing how mutations in the HDAC8 gene disrupt the biology of proteins that control both gene expression and cell division, the research sheds light on this disease, which causes intellectual disability, limb deformations and other disabilities resulting from impairments in early development.

"As we better understand how CdLS operates at the level of cell biology, we will be better able to define strategies for devising treatments ...

Modeling reveals significant climatic impacts of megapolitan expansion

2012-08-13

TEMPE, Ariz. – According to the United Nations' 2011 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects, global urban population is expected to gain more than 2.5 billion new inhabitants through 2050. Such sharp increases in the number of urban dwellers will require considerable conversion of natural to urban landscapes, resulting in newly developing and expanding megapolitan areas. Could climate impacts arising from built environment growth pose additional concerns for urban residents also expected to deal with impacts resulting from global climate change?

In the first study to ...

Unraveling intricate interactions, 1 molecule at a time

2012-08-13

A team of researchers at Columbia Engineering, led by Applied Physics and Applied Mathematics Associate Professor Latha Venkataraman and in collaboration with Mark Hybertsen from the Center for Functional Nanomaterials at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory, has succeeded in performing the first quantitative characterization of van der Waals interactions at metal/organic interfaces at the single-molecule level.

In a study published online August 12 in the Advance Online Publication on Nature Materials's website , the team has shown the existence ...

Differences in the genomes of related plant pathogens

2012-08-13

This press release is available in German.

Many crop plants worldwide are attacked by a group of fungi that numbers more than 680 different species. After initial invasion, they first grow stealthily inside living plant cells, but then switch to a highly destructive life-style, feeding on dead cells. While some species switch completely to host destruction, others maintain stealthy and destructive modes simultaneously. A team of scientists led by Richard O'Connell from the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research in Cologne and Lisa Vaillancourt from University ...

Smelling a skunk after a cold

2012-08-13

CHICAGO --- Has a summer cold or mold allergy stuffed up your nose and dampened your sense of smell? We take it for granted that once our nostrils clear, our sniffers will dependably rebound and alert us to a lurking neighborhood skunk or a caramel corn shop ahead.

That dependability is no accident. It turns out the brain is working overtime behind the scenes to make sure the sense of smell is just as sharp after the nose recovers.

A new Northwestern Medicine study shows that after the human nose is experimentally blocked for one week, brain activity rapidly ...

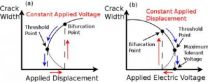

A pre-crack might propagate or stick under mechanical and electrical loading

2012-08-13

Fracture under combined mechanical and electric loading is currently a hot research area in the global fracture community, while electric sticking is a major concern in the design and fabrication of micro/nanoelectromechanical systems. Professor ZHANG Tong-Yi and his student, Mr. Tao Xie, from the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, found that the two problems are switchable, depending on the loading conditions, sample geometries and material properties. Based on his 20-year research experience on the fracture of dielectric ...

'Harmless' condition shown to alter brain function in elderly

2012-08-13

OAK BROOK, Ill. – Researchers at the Mayo Clinic say a common condition called leukoaraiosis, made up of tiny areas in the brain that have been deprived of oxygen and appear as bright white dots on MRI scans, is not a harmless part of the aging process, but rather a disease that alters brain function in the elderly. Results of their study are published online in the journal Radiology.

"There has been a lot of controversy over these commonly identified abnormalities on MRI scans and their clinical impact," said Kirk M. Welker, M.D., assistant professor of radiology in ...