(Press-News.org) Researchers at a recent worldwide conference on fusion power have confirmed the surprising accuracy of a new model for predicting the size of a key barrier to fusion that a top scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy's Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) has developed. The model could serve as a starting point for overcoming the barrier. "This allows you to depict the size of the challenge so you can think through what needs to be done to overcome it," said physicist Robert Goldston, the Princeton University professor of astrophysical sciences and former PPPL director who developed the model.

Goldston was among physicists who presented aspects of the model in late May to the 20th Annual International Conference on Plasma Surface Interactions in Aachen, Germany. Some 400 researchers from around the world attended the conference. Results of the model have been "eerily close" to the data, said Thomas Eich, a senior scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics in Garching, Germany, who gave an invited talk on his measurements. The agreement appears too close to have happened by chance, Eich added.

Goldston's model predicts the width of what physicists call the "scrape-off layer" in tokamaks, the most widely used fusion facilities. Such devices confine hot, electrically charged gas, or plasma, in powerful magnetic fields. But heat inevitably flows through the system and becomes separated, or scraped off, from the edge of the plasma and flows into an area called the divertor chamber.

The challenge is to prevent a thin and highly concentrated layer of heat from reaching and damaging the plate that sits at the bottom of the divertor chamber and absorbs the scrape-off flow. Such damage would halt fusion reactions, which take place when the atomic nuclei, or ions, inside the plasma merge and release energy. "If nothing was done and you took this right on the chin, it could be a knockout blow," said Goldston, who published his model in January in the journal Nuclear Fusion.

Solving this problem will be vital for future machines like ITER, the world's most powerful tokamak, which the European Union, the United States and five other countries are building in France to demonstrate fusion as a source of clean and abundant energy. The project is designed to produce 500 megawatts of fusion power in 400 second-long pulses, which will require researchers to spread the scrape-off heat as much as possible to protect the divertor plate.

Goldston's model could help guide such efforts. He began pondering the width of the heat flux during an international physics conference in South Korea in 2010. Looking at the latest scrape-off layer data based on improved measurements, he estimated—literally on an envelope—that the new widths could be produced without plasma turbulence, a factor that is typically considered but is notoriously difficult to calculate. This led him to search for a way to estimate the width of the surprisingly thin layer, and to gauge how the width would vary as conditions such as the amount of electrical current in the plasma varied.

The way plasma flows inside tokamaks provided the major clue. The ions within the charged gas gyrate swiftly along the magnetic field lines while drifting slowly across the lines. At the same time, the electrons also in the plasma travel very rapidly along the lines and carry away most of the heat. Goldston arrived at his prediction by determining how fast these subatomic particles flow into the divertor region, and how long it therefore takes them to reach it. The result "is what we call a 'heuristic' estimate, based on the key aspects of the physics, but not a detailed calculation," said Goldston.

His estimate confirmed what Goldston had suspected: the width of the scrape-off layer nearly matched the results of a calculation, made without considering turbulence, for determining how far the ions drift away from their field lines. "What's stunning is how closely the values correspond to the data, both in absolute value and in variation with the plasma current, magnetic field, machine size and input power," Goldston said. "This does not mean that turbulence plays no role, but it suggests that for the highest performance conditions, where turbulence is weakest, the motion of the ions is dominated by non-turbulent drift effects." This will be true in the case of ITER, he added, since it is designed to operate in high-performance conditions.

Researchers are developing techniques for widening the scrape-off layer. Such methods include pumping gas into the divertor region to keep some heat from reaching the plate. Physicists use deuterium, a form of hydrogen, to block the heat, and are injecting nitrogen to turn other parts of the heat into ultraviolet light. (While charged deuterium ions are already in the plasma, the deuterium gas that is injected into the divertor region to block the heat is not electrically charged.)

These strategies look promising. "We know that they will work," said Goldston. "The outstanding question is whether they will work completely enough" to mitigate the heat flux at ITER's highest power levels, without introducing so much gas that it cools the fuel. Physicists around the world are conducting experiments to understand the process better.

For Goldston, calculating the width of the scrape-off layer marks the latest research effort in a 40-year career at PPPL, which began when he was a graduate student. Along the way he helped to pioneer techniques for heating the plasma, and developed a widely used method called "Goldston scaling" for predicting how long heat is retained in a tokamak plasma.

"First, heat is injected into the plasma," Goldston said of how tokamaks operate. "Second, that heat is retained while much more heat is generated by fusion reactions. Finally, the resulting heat has to come out of the plasma. Without thinking about it, I have been following heat along this trajectory throughout my whole research career," he added. "We have made great progress on the first two steps, and now the most exciting challenge, to me, is the one that comes because of our success so far. Now we need to learn to handle the the outflow of heat from a high-power fusion energy source."

INFORMATION:

The Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and managed by Princeton University, advances the coupled fields of fusion energy and plasma physics. Fusion is the process that powers the sun and the stars. In the interior of stars, matter is converted into energy by the fusion, or joining, of the nuclei of light atoms to form heavier elements. At PPPL, physicists use a magnetic field to confine plasma. Scientists hope eventually to use fusion energy for the generation of electricity. http://www.pppl.gov/

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Scientist finds new way to predict heat layer troublemaker

A boon to fusion

2012-08-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Specific toxic byproduct of heat-processed food may lead to increased body weight and diabetes

2012-08-21

Researchers at Mount Sinai School of Medicine have identified a common compound in the modern diet that could play a major role in the development of abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. The findings are published in the August 20, 2012 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The research team, led by Helen Vlassara, MD, Professor and Director of the Division of Experimental Diabetes and Aging, found that mice with sustained exposure to the compound, methyl-glyoxal (MG), developed significant abdominal weight gain, early insulin ...

UCSB scientists examine effects of manufactured nanoparticles on soybean crops

2012-08-21

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) –– Sunscreens, lotions, and cosmetics contain tiny metal nanoparticles that wash down the drain at the end of the day, or are discharged after manufacturing. Those nanoparticles eventually end up in agricultural soil, which is a cause for concern, according to a group of environmental scientists that recently carried out the first major study of soybeans grown in soil contaminated by two manufactured nanomaterials (MNMs).

The team was led by scientists at UC Santa Barbara's Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. The team is also affiliated ...

Information overload in the era of 'big data'

2012-08-21

Botany is plagued by the same problem as the rest of science and society: our ability to generate data quickly and cheaply is surpassing our ability to access and analyze it. In this age of big data, scientists facing too much information rely on computers to search large data sets for patterns that are beyond the capability of humans to recognize—but computers can only interpret data based on the strict set of rules in their programming.

New tools called ontologies provide the rules computers need to transform information into knowledge, by attaching meaning to data, ...

Stroke disrupts how brain controls muscle synergies

2012-08-21

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The simple act of picking up a pencil requires the coordination of dozens of muscles: The eyes and head must turn toward the object as the hand reaches forward and the fingers grasp it. To make this job more manageable, the brain's motor cortex has implemented a system of shortcuts. Instead of controlling each muscle independently, the cortex is believed to activate muscles in groups, known as "muscle synergies." These synergies can be combined in different ways to achieve a wide range of movements.

A new study from MIT, Harvard Medical School and the ...

Nanoparticles added to platelets double internal injury survival rate

2012-08-21

Nanoparticles tailored to latch onto blood platelets rapidly create healthy clots and nearly double the survival rate in the vital first hour after injury, new research shows.

"We knew an injection of these nanoparticles stopped bleeding faster, but now we know the bleeding is stopped in time to increase survival following trauma," said Erin Lavik, a professor of biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University and leader of the effort.

The researchers are developing synthetic platelets that first responders and battlefield medics could carry with them to stabilize ...

Breast density does not influence breast cancer death among breast cancer patients

2012-08-21

The risk of dying from breast cancer was not related to high mammographic breast density in breast cancer patients, according to a study published August 20 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

One of the strongest risk factors for non-familial breast cancer is elevated mammographic breast density. While women with elevated mammographic breast density have a higher risk of developing breast cancer, it is not established whether a higher density indicates a lower chance of survival in breast cancer patients.

In order to determine if higher mammographic breast ...

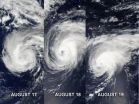

NASA satellites capture 3 days of Hurricane Gordon's Atlantic track

2012-08-21

NASA's Terra and Aqua satellite have captured Hurricane Gordon over three days as it neared the Azores Islands in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Gordon weakened to a tropical storm on August 20.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, or MODIS, is an instrument that flies onboard NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites and provides high-resolution imagery to users. When NASA's Terra satellite flew over Gordon on August 17 at 9:30 a.m. EDT it was a tropical storm and did not have a visible eye. It was followed up by a fly over of NASA's Aqua satellite on August 18 at ...

First evidence discovered of planet's destruction by its star

2012-08-21

The first evidence of a planet's destruction by its aging star has been discovered by an international team of astronomers. The evidence indicates that the missing planet was devoured as the star began expanding into a "red giant" -- the stellar equivalent of advanced age. "A similar fate may await the inner planets in our solar system, when the Sun becomes a red giant and expands all the way out to Earth's orbit some five-billion years from now," said Alexander Wolszczan, Evan Pugh Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Penn State University, who is one of the members ...

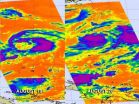

NASA watches as Tropical Storm Bolaven develops

2012-08-21

Tropical Storm Bolaven was born over the weekend of August 18-19 in the western North Pacific, and NASA captured infrared satellite imagery of its birth and growth.

NASA's Aqua satellite has been monitoring the birth and progress of Tropical Storm Bolaven in the western North Pacific from Aug 19-20, 2012. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument has provided infrared satellite imagery that shows the development of colder thunderstorm cloud-top temperatures, that were indicative of strengthening storms. Tropical Storm Bolaven also took more of a rounded shape ...

Infants' avoidance of drop-off reflects specific motor ability, not fear

2012-08-21

Researchers have long studied infants' perceptions of safe and risky ground by observing their willingness to cross a visual cliff, a large drop-off covered with a solid glass surface. In crawling, infants grow more likely to avoid the apparent drop-off, leading researchers to conclude that they have a fear of heights. Now a new study has found that although infants learn to avoid the drop-off while crawling, this knowledge doesn't transfer to walking. This suggests that what infants learn is to perceive the limits of their ability to crawl or walk, not a generalized fear ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A kaleidoscope of cosmic collisions: the new catalogue of gravitational signals from LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA

New catalog more than doubles the number of gravitational-wave detections made by LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA observatories

Antifibrotic drug shows promise for premature ovarian insufficiency

Altered copper metabolism is a crucial factor in inflammatory bone diseases

Real-time imaging of microplastics in the body improves understanding of health risks

Reconstructing the world’s ant diversity in 3D

UMD entomologist helps bring the world’s ant diversity to life in 3D imagery

ESA’s Mars orbiters watch solar superstorm hit the Red Planet

The secret lives of catalysts: How microscopic networks power reactions

Molecular ‘catapult’ fires electrons at the limits of physics

Researcher finds evidence supporting sucrose can help manage painful procedures in infants

New study identifies key factors supporting indigenous well-being

Bureaucracy Index 2026: Business sector hit hardest

ECMWF’s portable global forecasting model OpenIFS now available for all

Yale study challenges notion that aging means decline, finds many older adults improve over time

Korean researchers enable early detection of brain disorders with a single drop of saliva!

Swipe right, but safer

Duke-NUS scientists identify more effective way to detect poultry viruses in live markets

Low-intensity treadmill exercise preconditioning mitigates post-stroke injury in mouse models

How moss helped solve a grave-robbing mystery

How much sleep do teens get? Six-seven hours.

Patients regain weight rapidly after stopping weight loss drugs – but still keep off a quarter of weight lost

GLP-1 diabetes drugs linked to reduced risk of addiction and substance-related death

Councils face industry legal threats for campaigns warning against wood burning stoves

GLP-1 medications get at the heart of addiction: study

Global trauma study highlights shared learning as interest in whole blood resurges

Almost a third of Gen Z men agree a wife should obey her husband

Trapping light on thermal photodetectors shatters speed records

New review highlights the future of tubular solid oxide fuel cells for clean energy systems

Pig farm ammonia pollution may indirectly accelerate climate warming, new study finds

[Press-News.org] Scientist finds new way to predict heat layer troublemakerA boon to fusion