(Press-News.org) A team of researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE's) Ames Laboratory has answered a key question concerning the widely-used Fenton reaction – important in wastewater treatment to destroy hazardous organic chemicals and decontaminate bacterial pathogens and in industrial chemical production. The naturally occurring reaction was first discovered in 1894 by H.J.H. Fenton, a British chemist at Cambridge, and involves hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and iron.

How the Fenton reaction actually happens has remained in contention. Scientists have long debated whether it was a hydroxyl (OH) radical or a form of iron known as the ferryl ion, [Fe(IV)O]2+, that functioned as the reaction intermediate for the Fenton reaction, with data to support both theories.

Now, Andreja Bakac and Oleg Pestovsky, scientists at Ames Laboratory in the Division of Chemical and Biological Sciences, and chemistry graduate student Hajem Bataineh, have proved that the reaction can take different paths depending on the pH of the reaction environment. In an acidic environment, the intermediate is an OH radical; at neutral pH, the intermediate is the ferryl ion.

"This is enormous when you think about all the work that went into trying to solve this issue when the acidity of the solution was not considered as a parameter. It certainly varied from one work to the next, and may explain the confusion that grew out of contradicting results in the literature," said Bakac.

So, is the reaction fundamental? Yes. Simple? No. The exact nature of the mechanism of the Fenton reaction has eluded science for decades, and has been all that time a subject of close inquiry—and debate.

"The reaction takes place between iron which is widespread on Earth, and hydrogen peroxide which is derived from oxygen and also present almost everywhere on this planet. You know you are facing a real challenge when the reaction between two very common compounds has not been fully explained in a hundred years, despite all the efforts," said Bakac.

Over those past hundred years, the Fenton intermediates were reduced to two, the hydroxyl radical or the ferryl ion.

Much was known already about hydroxyl radicals. However, it wasn't until 2005 that Bakac's research group, in collaboration with groups at Carnegie Mellon and University of Minnesota, was able to directly characterize the ferryl ion and study its reactions. This gave them the ability to compare the two potential intermediates.

"We found that these two species, in many of the reactions, behave pretty much the same, which would make it very difficult to distinguish between them," explained Bakac of the earlier research. "The breakthrough came with some unique reactions that one intermediate will do and the other one will not, or where the products were different, and that gave us the key.

"We were thrilled to obtain a clear and unambiguous answer. The intermediate was the OH radical, and not the ferryl ion. We published the paper, we had a write up in Chemical and Engineering News; this was very exciting."

But the question still didn't seem settled. Other scientists continued to assert that ferryl was the intermediate.

"We thought how can this be? We just proved that it isn't. There were also some theoretical papers that came out at the time, also supporting the ferryl ion."

The continued debate prompted Bakac and her research partners to look at the potential effect of reaction conditions, specifically the acidity of the solution. That led to the discovery that either intermediate can be involved, depending on the pH of the reaction environment.

The discovery not only solves a long-running debate in academic chemistry, it opens up possibilities for new ways to use the reaction.

"If we can understand fully what's going on, then we can take advantage of that understanding and develop new uses for the Fenton reaction," said Bakac. The discovery could lead to catalytic reactions using widely available iron in neutral conditions, and environmentally friendlier processes in everything from wastewater treatment to industrial oxidations.

"It becomes not just a better understood reaction, but a more useful one from a practical standpoint," said Bakac.

INFORMATION:

The findings were published in the journal Chemical Science and co-authored by Bakac, Pestovsky and Bataineh.

The research is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit the Office of Science website at science.energy.gov/.

The Ames Laboratory is a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science national laboratory operated by Iowa State University. The Laboratory creates innovative materials, technologies and energy solutions. We use our expertise, unique capabilities and interdisciplinary collaborations to solve global challenges.

Ames Laboratory scientists crack long-standing chemistry mystery

2012-08-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ancient fossils reveal how the mollusc got its teeth

2012-08-22

TORONTO, ON – The radula sounds like something from a horror movie – a conveyor belt lined with hundreds of rows of interlocking teeth. In fact, radulas are found in the mouths of most molluscs, from the giant squid to the garden snail. Now, a "prototype" radula found in 500-million-year-old fossils studied by University of Toronto graduate student Martin Smith, shows that the earliest radula was not a flesh-rasping terror, but a tool for humbly scooping food from the muddy sea floor.

The Cambrian animals Odontogriphus and Wiwaxia might not have been much to look at ...

UCI microbiologists find new approach to fighting viral illnesses

2012-08-22

Irvine, Calif., Aug. 22, 2012 — By discovering how certain viruses use their host cells to replicate, UC Irvine microbiologists have identified a new approach to the development of universal treatments for viral illnesses such as meningitis, encephalitis, hepatitis and possibly the common cold.

The UCI researchers, working with Dutch colleagues, found that certain RNA viruses hijack a key DNA repair activity of human cells to produce the genetic material necessary for them to multiply.

For many years, scientists have known that viruses rely on functions provided by ...

Australian general practitioners in training spend less time with peds patients than with adults

2012-08-22

Ann Arbor, Mich. — Australian doctors-in-training spend significantly less time consulting with pediatric patients than they do with adults, according to a new study published in the journal Australian Family Physician.

The study found that the proportion of longer consultations – more than 20 minutes -- for children was significantly less than that for adults and seniors among general practice registrars, says Gary Freed, M.D., M.P.H., the lead author on the study and Australian-American health policy fellow, Australian Health Workforce Institute at the University of ...

Close contact with young people at risk of suicide has no effect

2012-08-22

Researchers, doctors and patients tend to agree that during the high-risk period after an attempted suicide, the treatment of choice is close contact, follow-up and personal interaction in order to prevent a tragic repeat. Now, however, new research shows that this strategy does not work. These surprising results from Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Denmark and the University of Copenhagen have just been published in the British Medical Journal.

Researchers from Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Denmark and the University of Copenhagen have ...

Rewired visual input to sound-processing part of the brain leads to compromised hearing

2012-08-22

ATLANTA – Scientists at Georgia State University have found that the ability to hear is lessened when, as a result of injury, a region of the brain responsible for processing sounds receives both visual and auditory inputs.

Yu-Ting Mao, a former graduate student under Sarah L. Pallas, professor of neuroscience, explored how the brain's ability to change, or neuroplasticity, affected the brain's ability to process sounds when both visual and auditory information is sent to the auditory thalamus.

The study was published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

The auditory thalamus ...

Intense prep for law school admission test alters brain structure

2012-08-22

Intensive preparation for the Law School Admission Test (LSAT) actually changes the microscopic structure of the brain, physically bolstering the connections between areas of the brain important for reasoning, according to neuroscientists at the University of California, Berkeley.

The results suggest that training people in reasoning skills – the main focus of LSAT prep courses – can reinforce the brain's circuits involved in thinking and reasoning and could even up people's IQ scores.

"The fact that performance on the LSAT can be improved with practice is not new. ...

Study shows long-term effects of radiation in pediatric cancer patients

2012-08-22

For many pediatric cancer patients, total body irradiation (TBI) is a necessary part of treatment during bone marrow transplant– it's a key component of long term survival. But lengthened survival creates the ability to notice long term effects of radiation as these youngest cancer patients age. A University of Colorado Cancer Center study recently published in the journal Pediatric Blood & Cancer details these late effects of radiation.

"These kids basically lie on a table and truly do get radiation from head to toe. There is a little blocking of the lungs, but nothing ...

New laboratory test assesses how DNA damage affects protein synthesis

2012-08-22

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Transcription is a cellular process by which genetic information from DNA is copied to messenger RNA for protein production. But anticancer drugs and environmental chemicals can sometimes interrupt this flow of genetic information by causing modifications in DNA.

Chemists at the University of California, Riverside have now developed a test in the lab to examine how such DNA modifications lead to aberrant transcription and ultimately a disruption in protein synthesis.

The chemists report that the method, called "competitive transcription and adduct ...

NASA sees an active tropical Atlantic again

2012-08-22

The Atlantic Ocean is kicking into high gear with low pressure areas that have a chance at becoming tropical depressions, storms and hurricanes. Satellite imagery from NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites have provided visible, infrared and microwave data on four low pressure areas. In addition, NASA's GOES Project has been producing imagery of all systems using NOAA's GOES-13 satellite to see post-Tropical Storm Gordon, Tropical Depression 9, and Systems 95L and 96L.

Tropical Storm Gordon is no longer a tropical storm and is fizzling out east of the Azores. Tropical Depression ...

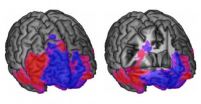

Thinking and choosing in the brain

2012-08-22

PASADENA, Calif.—The frontal lobes are the largest part of the human brain, and thought to be the part that expanded most during human evolution. Damage to the frontal lobes—which are located just behind and above the eyes—can result in profound impairments in higher-level reasoning and decision making. To find out more about what different parts of the frontal lobes do, neuroscientists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) recently teamed up with researchers at the world's largest registry of brain-lesion patients. By mapping the brain lesions of these patients, ...