(Press-News.org) WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – Researchers have created a new type of miniature pump activated by body heat that could be used in drug-delivery patches powered by fermentation.

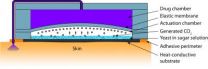

The micropump contains bakers yeast and sugar in a small chamber. When water is added and the patch is placed on the skin, the body heat and the added water causes the yeast and sugar to ferment, generating a small amount of carbon dioxide gas. The gas pushes against a membrane and has been shown to continually pump for several hours, said Babak Ziaie, a Purdue University professor of electrical and computer engineering and biomedical engineering.

Such miniature pumps could make possible drug-delivery patches that use arrays of "microneedles" to deliver a wider range of medications than now possible with conventional patches. Unlike many other micropumps under development or in commercial use, the new technology requires no batteries, said Ziaie, who is working with doctoral student Manuel Ochoa.

"This just needs yeast, sugar, water and your own body heat," Ziaie said.

The robustness of yeast allows for long shelf life, and the design is ideal for mass production, Ochoa said.

"It would be easy to fabricate because it's just a few layers of polymers sandwiched together and bonded," he said.

Findings were detailed in a research paper published online in August in the journal Lab on a Chip. The paper was written by Ochoa and Ziaie, and the research is based at Purdue's Birck Nanotechnology Center in the university's Discovery Park.

The "the microorganism-powered thermopneumatic pump" is made out of layers of a rubberlike polymer, called polydimethylsiloxane, which is used commercially for diaphragms in pumps. The prototype is 1.5 centimeters long.

Current "transdermal" patches are limited to delivering drugs that, like nicotine, are made of small hydrophobic molecules that can be absorbed through the skin, Ziaie said.

"Many drugs, including those for treating cancer and autoimmune disorders cannot be delivered with patches because they are large molecules that won't go through the skin," he said. "Although transdermal drug delivery via microneedle arrays has long been identified as a viable and promising method for delivering large hydrophilic molecules across the skin, a suitable pump has been hard to develop."

Patches that used arrays of tiny microneedles could deliver a multitude of drugs, and the needles do not cause pain because they barely penetrate the skin, Ziaie said. The patches require a pump to push the drugs through the narrow needles, which have a diameter of about 20 microns, or roughly one-fourth as wide as a human hair.

Most pumps proposed for drug-delivery applications rely on an on-board power source, which is bulky, costly and requires complex power-management circuits to conserve battery life.

"Our approach is much more simple," Ziaie said. "It could be a disposable transdermal pump. You just inject water into the patch and place it on your skin. After it's used up, you would through it away."

Researchers have filed an application for a provisional patent on the device.

INFORMATION:

Writer: Emil Venere, 765-494-4709, venere@purdue.edu

Source: Babak Ziaie, 765-494-0725, bziaie@purdue.edu

Related websites:

Babak Ziaie: https://engineering.purdue.edu/ECE/People/profile?resource_id=2839

Birck Nanotechnology Center: http://www.purdue.edu/discoverypark/nanotechnology/

IMAGE CAPTION:

This diagram shows a new type of miniature pump activated by body heat that could be used in drug-delivery patches powered by fermentation. The micropump works by harnessing the pressure generated by fermenting yeast. Such drug-delivery patches might use arrays of "microneedles" to deliver a wider range of medications than now possible with conventional patches. (Manuel Ochoa, Purdue University)

A publication-quality image is available at http://news.uns.purdue.edu/images/2012/ziaie-drugpump.jpg

ABSTRACT

A fermentation-powered thermopneumatic pump for biomedical applications

Manuel Ochoa ac and Babak Ziaie *abc

a School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Purdue University

b Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering

c Birck Nanotechnology Center

We present a microorganism-powered thermopneumatic pump that utilizes temperature-dependent slow-kinetics gas (carbon dioxide) generating fermentation of yeast as a pressure source. The pump consists of stacked layers of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and a silicon substrate that form a drug reservoir, and a yeast-solution-filled working chamber. The pump operates by the displacement of a drug due to the generation of gas produced via yeast fermentation carried out at skin temperatures. The robustness of yeast allows for long shelf life under extreme environmental conditions (50 °C, >250 MPa, 5-8% humidity). The generation of carbon dioxide is a linear function of time for a given temperature, thus allowing for a controlled volume displacement. A polymeric prototype (dimensions 15 mm x 15 mm x 10 mm) with a slow flow rate of

Body heat, fermentation drive new drug-delivery 'micropump'

2012-09-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Hearing impaired ears hear differently in noisy environments

2012-09-12

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - The world continues to be a noisy place, and Purdue University researchers have found that all that background chatter causes the ears of those with hearing impairments to work differently.

"When immersed in the noise, the neurons of the inner ear must work harder because they are spread too thin," said Kenneth S. Henry, a postdoctoral researcher in Purdue's Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences. "It's comparable to turning on a dozen television screens and asking someone to focus on one program. The result can be fuzzy because these ...

Planets can form in the galactic center

2012-09-12

At first glance, the center of the Milky Way seems like a very inhospitable place to try to form a planet. Stars crowd each other as they whiz through space like cars on a rush-hour freeway. Supernova explosions blast out shock waves and bathe the region in intense radiation. Powerful gravitational forces from a supermassive black hole twist and warp the fabric of space itself.

Yet new research by astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics shows that planets still can form in this cosmic maelstrom. For proof, they point to the recent discovery of a ...

Improved nanoparticles deliver drugs into brain

2012-09-12

The brain is a notoriously difficult organ to treat, but Johns Hopkins researchers report they are one step closer to having a drug-delivery system flexible enough to overcome some key challenges posed by brain cancer and perhaps other maladies affecting that organ.

In a report published online on August 29 in Science Translational Medicine, the Johns Hopkins team says its bioengineers have designed nanoparticles that can safely and predictably infiltrate deep into the brain when tested in rodent and human tissue.

"We are pleased to have found a way to prevent drug-embedded ...

Newly discovered letters and translated German ode expand Texas link to infamous Bone Wars

2012-09-12

In the late 1800s, a flurry of fossil speculation across the American West escalated into a high-profile national feud called the Bone Wars.

Drawn into the spectacle were two scientists from the Lone Star State: geologist Robert T. Hill, now acclaimed as the Father of Texas Geology, and naturalist Jacob Boll, who made many of the state's earliest fossil discoveries.

Hill and Boll had supporting roles in the Bone Wars through their work for one of the feud's antagonists, Edward Drinker Cope. A new study by vertebrate paleontologist Louis L. Jacobs at Southern Methodist ...

Scripps Research scientists devise powerful new method for finding therapeutic antibodies

2012-09-12

LA JOLLA, CA, September 11, 2012 – Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute have found a new technique that should greatly speed the discovery of medically and scientifically useful antibodies, immune system proteins that detect and destroy invaders such as bacteria and viruses. New methods to discover antibodies are important because antibodies make up the fastest growing sector of human therapeutics; it is estimated that by 2014 the top-three selling drugs worldwide will be antibodies.

The new technique, described in an article this week published online ahead of ...

Ageism presents dilemmas for policymakers worldwide

2012-09-12

The negative consequences of age discrimination in many countries are more widespread than discrimination due to race or gender, yet differential treatment based on a person's age is often seen as more acceptable and even desirable, according to the newest edition of the Public Policy & Aging Report (PP&AR). This publication, which features cross-national perspectives, was jointly produced by The Gerontological Society of America (GSA) and AGE UK.

The PP&AR explores how discriminatory behaviors manifest themselves, steps that are being taken to address those behaviors, ...

Sliding metals show fluidlike behavior, new clues to wear

2012-09-12

"We see phenomena normally associated with fluids, not solids," said Srinivasan Chandrasekar, a professor of industrial engineering at Purdue University, working with postdoctoral research associates Narayan Sundaram and Yang Guo.

Numerous mechanical parts, from bearings to engine pistons, undergo such sliding.

"It has been known that little pieces of metal peel off from sliding surfaces," Chandrasekar said. "The conventional view is that this requires many cycles of rubbing, but what we are saying is that when you have surface folding you don't need too many cycles for ...

NASA's Global Hawk investigating Atlantic Tropical Depression 14

2012-09-12

NASA's Hurricane and Severe Storm Sentinel (HS3) airborne mission sent an unmanned Global Hawk aircraft this morning to study newborn Tropical Depression 14 in the central Atlantic Ocean that seems primed for further development. The Global Hawk left NASA's Wallops Flight Facility on Wallops Island, Va., this morning for a planned 26-hour flight to investigate the depression.

NASA's latest hurricane science field campaign began on Sept. 7 when the Global Hawk flew over Hurricane Leslie in the Atlantic Ocean. HS3 marks the first time NASA is flying Global Hawks from the ...

Scrub jays react to their dead

2012-09-12

Western scrub jays summon others to screech over the body of a dead jay, according to new research from the University of California, Davis. The birds' cacophonous "funerals" can last for up to half an hour.

Anecdotal reports have suggested that other animals, including elephants, chimpanzees and birds in the crow family, react to dead of their species, said Teresa Iglesias, the UC Davis graduate student who carried out the work. But few experimental studies have explored this behavior.

The new research by Iglesias and her colleagues appears in the Aug. 27 issue of ...

Protein linked to therapy resistance in breast cancer

2012-09-12

A gene that may possibly belong to an entire new family of oncogenes has been linked by researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) to the resistance of breast cancer to a well-regarded and widely used cancer therapy.

One of the world's leading breast cancer researchers, Mina Bissell, Distinguished Scientist with Berkeley Lab's Life Sciences Division, led a study in which a protein known as FAM83A was linked to resistance to the cancer drugs known as EGFR-TKIs (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Tyrosine Kinase ...