(Press-News.org) Indoor tanning beds can cause non-melanoma skin cancer – and the risk is greater the earlier one starts tanning, according to a new analysis led by UCSF.

Indoor tanning is already an established risk factor for malignant melanoma, the less common but deadliest form of skin cancer. Now, the new study confirms that indoor tanning significantly increases the risk of non-melanoma skin cancers, the most common human skin cancers.

In the most extensive examination of published findings on the subject, the researchers estimate that indoor tanning is responsible for more than 170,000 new cases annually of non-melanoma skin cancers in the United States – and many more worldwide.

Young people who patronize tanning salons before age 25 have a significantly higher risk of developing basal cell carcinomas compared to those who never use the popular tanning booths, the researchers reported.

The study will be published online October 2, 2012 in BMJ, the British general medical journal.

"The numbers are striking – hundreds of thousands of cancers each year are attributed to tanning beds,'' said Eleni Linos, MD, DrPH, an assistant professor of dermatology at UCSF and senior author of the study. "This creates a huge opportunity for cancer prevention.''

The study was a meta-analysis and systematic review of medical articles published since 1985 involving some 80,000 people in six countries and data extending back to 1977.

The popularity of indoor tanning in the United States first began in the 1970s, and now millions of people annually patronize tanning salons. The National Cancer Institute and the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2010 reported that 5.6 percent of the American public used indoor tanning during the prior year, with higher rates among women, whites, and young adults.

Currently, there are some 19,000 indoor tanning businesses, according to an industry trade organization.

But in pursuit of golden hues, many people may unknowingly subject themselves to dermatological danger.

The World Health Organization has said that ultraviolet tanning devices cause cancer in people and the International Agency for Research on Cancer considers indoor tanning a "Class 1'' carcinogen. Government officials in the U.S. and abroad are increasingly restricting and regulating tanning facilities.

The new study adds to the mounting evidence on the harms of indoor tanning, showing significant elevated risk of the most common forms of skin cancer.

"Several earlier studies suggested a link between non-melanoma skin cancer and indoor tanning. Our goal was to synthesize the available data to be able to draw a firm conclusion about this important question,'' said co-author Mary-Margaret Chren, MD, professor of dermatology at UCSF.

The researchers studied both early life exposure and regular use of tanning booths.

Those who exposed themselves to indoor tanning had a 67 percent higher risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma and a 29 percent higher risk of developing basal cell carcinoma, compared to people who never did indoor tanning.

The scientists noted several limitations including the broad timeframe that the data spans. Also, indoor tanning devices have changed over the years "from high UVB output to predominantly UVA output,'' the authors said. But, they point out, numerous studies have indicated that both UVB and UVA can cause significant skin damage.

"Australia and Europe have already led the way in banning tanning beds for children and teenagers, and Brazil has completely banned tanning beds for all ages,'' Linos said. "I hope that our study supports policy and public health campaigns to limit this carcinogen in the United States.''

INFORMATION:

Co-authors are Mackenzie Wehner, a Doris Duke Research Fellow at UCSF; Melissa Shive, a medical student at UCSF; Jiali Han, PhD, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School; and Abrar Qureshi, MD, MPH, dermatology vice chairman at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

The project was supported by UCSF's Clinical and Translational Science Institute KL2 program, and the National Institute of Health.

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest. Chren serves as a consultant to Genentech.

UCSF is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care.

Follow UCSF

UCSF.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | Twitter.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

Tanning beds linked to non-melanoma skin cancer

2012-10-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Allergy rises not down to being too clean, just losing touch with 'old friends'

2012-10-03

A new scientific report out today from the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene (IFH) dismantles the myth that the epidemic rise in allergies in recent years has happened because we're living in sterile homes and overdoing hygiene.

But far from saying microbial exposure is not important, the report concludes that losing touch with microbial 'old friends' may be a fundamental factor underlying rises in an even wider array of serious diseases. As well as allergies, there are numerous other 'chronic inflammatory diseases' (CIDs) such as Type 1 diabetes and multiple ...

A mammal lung, in 3-D

2012-10-03

VIDEO:

The video shows the imaging of a section of a mouse lung. As the image rotates, more respiratory branches (bronchioles) are shown, along with three acini (yellow, green and orange...

Click here for more information.

Amidst the extraordinarily dense network of pathways in a mammal lung is a common destination. There, any road leads to a cul-de-sac of sorts called the pulmonary acinus. This place looks like a bunch of grapes attached to a stem (acinus means "berry" ...

University of Alberta has $12.3-billion impact on Alberta economy

2012-10-03

(Edmonton) The University of Alberta's impact on the Alberta economy is estimated to be $12.3 billion, which is five per cent of the province's gross domestic product—or the equivalent of having 135 Edmonton Oilers NHL teams in Alberta, according to a new study.

"When a university educates a population, it's the whole region that benefits," said study co-author Anthony Briggs, an assistant professor in the Alberta School of Business at the U of A. "We're not looking at the cost of the education and research, which is just one slice, but estimating the value of the investment. ...

Visionary transparent memory a step closer to reality

2012-10-03

HOUSTON – (Oct. 2, 2012) – Researchers at Rice University are designing transparent, two-terminal, three-dimensional computer memories on flexible sheets that show promise for electronics and sophisticated heads-up displays.

The technique based on the switching properties of silicon oxide, a breakthrough discovery by Rice in 2008, was reported today in the online journal Nature Communications.

The Rice team led by chemist James Tour and physicist Douglas Natelson is making highly transparent, nonvolatile resistive memory devices based on the revelation that silicon ...

Starting antiretroviral therapy improves HIV-infected Africans' nutrition

2012-10-03

Starting HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy reduces food insecurity and improves physical health, thereby contributing to the disruption of a lethal syndemic, UCSF and Massachusetts General Hospital researchers have found in a study focused on sub-Saharan Africa.

The study was published this week in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes.

With more than 20 million people infected with HIV/AIDS and almost 240 million people lacking access to enough food, sub-Saharan Africa is experiencing co-epidemics of food insecurity and HIV/AIDS that intensify ...

For elephants, deciding to leave watering hole demands conversation, Stanford study shows

2012-10-03

STANFORD, Calif. — In the wilds of Africa, when it's time for a family of elephants gathered at a watering hole to leave, the matriarch of the group gives the "let's-go rumble" — as it's referred to in scientific literature — kicking off a coordinated and well-timed conversation, of sorts, between the leaders of the clan.

First, the head honcho moves away from the group, turns her back and gives a long, slightly modulated and — to human ears — soft rumble while steadily flapping her ears. This spurs a series of back and forth vocalizations, or rumbles, within the group ...

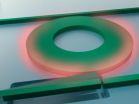

University of Minnesota engineers invent new device that could increase Internet download speeds

2012-10-03

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (10/02/2012) —A team of scientists and engineers at the University of Minnesota has invented a unique microscale optical device that could greatly increase the speed of downloading information online and reduce the cost of Internet transmission.

The device uses the force generated by light to flop a mechanical switch of light on and off at a very high speed. This development could lead to advances in computation and signal processing using light instead of electrical current with higher performance and lower power consumption.

The research results ...

1 glue, 2 functions

2012-10-03

Akron, Ohio, Oct. 2, 2012 — While the common house spider may be creepy, it also has been inspiring researchers to find new and better ways to develop adhesives for human applications such as wound healing and industrial-strength tape. Think about an adhesive suture strong enough to heal a fractured shoulder and that same adhesive designed with a light tackiness ideal for "ouch-free" bandages.

University of Akron polymer scientists and biologists have discovered that this house spider — in order to more efficiently capture different types of prey — performs an uncommon ...

Too little nitrogen may restrain plants' carbon storage capability, U of M paper shows

2012-10-03

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (10/02/2012) —Plants' ability to absorb increased levels of carbon dioxide in the air may have been overestimated, a new University of Minnesota study shows.

The study, published this week in the journal Nature Climate Change, shows that even though plants absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide and actually can benefit from higher levels of it, they may not get enough of the nutrients they need from typical soils to absorb as much CO2 as scientists had previously estimated. Carbon dioxide absorption is an important factor in mitigating fossil-fuel ...

Acoustic cell-sorting chip may lead to cell phone-sized medical labs

2012-10-03

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- A technique that uses acoustic waves to sort cells on a chip may create miniature medical analytic devices that could make Star Trek's tricorder seem a bit bulky in comparison, according to a team of researchers.

The device uses two beams of acoustic -- or sound -- waves to act as acoustic tweezers and sort a continuous flow of cells on a dime-sized chip, said Tony Jun Huang, associate professor of engineering science and mechanics, Penn State. By changing the frequency of the acoustic waves, researchers can easily alter the paths of the cells.

Huang ...