(Press-News.org) Printed circuit boards (PCBs) are core components in every mobile phone, television and computer. PCBs can be thought of as acting like a nervous system, forming a network that links the microchips mounted on the board and supplies them with power. One of the most important methods of fabricating large PCBs involves the precision electroplating of copper onto the PCB panel immersed in an acidic electrolyte bath. However, some of the titanium parts used in the electroplating process suffer substantial wear within a short space of time. Replacing these parts generates significant costs. A materials science research team at Saarland University has now developed a process that enables the damaged components to repair themselves while the PCB fabrication process continues. Atotech, the company responsible for manufacturing almost 90 percent of all PCBs used in mobile phones worldwide, is now saving several millions of euros each year as a result. The new process, for which a patent application has been filed, was developed jointly by the Saarbrücken research group led by Professor Mücklich and the project group from Atotech. Recently, the Steinbeis Foundation in Stuttgart has chosen to honour the team's achievements by conferring the Steinbeis Transfer Award 2012, which is bestowed annually for an outstanding example of technology transfer into the industrial sector.

Electronic components are becoming ever smaller and ever more powerful while at the same time having to be connected with one another in increasingly complex ways. "A printed circuit board today is an extremely complicated three-dimensional structure, that essentially acts like a central nervous system connecting all the various individual components," explains Professor Frank Mücklich, Professor of Functional Materials at Saarland University and Director of the Steinbeis Material Engineering Center Saarland (MECS). The method typically used for high-precision fabrication of large-surface PCBs is acid copper electroplating, in which the PCB panel is immersed in an acidic solution of copper ions, the electrolyte. A very high electric current flows through the board transporting copper ions in the electrolyte to the surface of the PCB and into the minute holes, known as vias, into which the leads or contact pins of the electronic components will later be inserted. "As a result, the PCB is covered with a uniform extremely thin coating of copper whose thickness is less than one tenth of the diameter of a human hair," says Mücklich.

The PCB panels are held in solution by acid-resistant titanium PCB plating clamps that guide the current onto the PCB panel. "These clamps have to withstand an enormous amount of electrical energy over an area of only a few square millimetres. The extremely powerful current generates sparks that are similar to a lightning discharge and that damage the clamps by eroding their surface each time the panels undergo plating," says Mücklich, describing the fundamental problem of modern electroplating systems. The Saarbrücken material scientists examined the damage mechanisms using not only electron microscopy, but also tomographic techniques that allow imaging down to the nano- and even atomic scales. "We came to realise that with spark temperatures of around several thousands of degrees the previous strategy of trying to develop materials with ever greater resistance to these extremely hot and destructive sparks was not going to prove successful," explains Mücklich. Even the use of very expensive precious metals, such as platinum, only delays but does not stop the onset of damage. Working together with engineers from Atotech, the material scientists and technologists at Saarland University came up with an extremely economical and reliable solution. According to Mücklich: "The new process is similar to the mechanism used to regenerate human skin when wounds heal."

The damaged clamps migrate in a circular path within the production facility as if on a carousel. And, like the PCBs that they hold, a new thin layer of copper is plated onto them. "We are essentially creating a recyclable wear layer on the clamps. This has the effect of immediately repairing any damage to the clamp surface and, quite incidentally, also increases the conductivity of the clamps several-fold," says Mücklich. The new process means that there is no longer any need for the complex procedure of removing and replacing the clamps at Atotech's many production facilities. The production process can therefore continue uninterrupted. "Atotech is the market leader in this field, operating more than 600 production facilities of this type around the world. This new development will result in savings of several millions of euros each year," says graduate engineer Bernd Schmitt, who has been Atotech's coordinator on the research project. Atotech and the scientists and engineers from Saarland University have now filed jointly for a patent application.

The process was developed by materials scientist Frank Mücklich and his research assistants Dominik Britz and Christian Selzner in the space of just one year. To enable the research to be conducted, Atotech installed a purpose-built (and very heavy) test facility at the Steinbeis Research Centre that is located on the Saarbrücken campus. In the first stage of the project, the researchers used new three-dimensional imaging techniques to study what goes on inside the titanium contacts during electroplating. "We used high-resolution electron microscopy as well as nanotomography and atom-probe tomography. The images recorded with these techniques are then assembled in a computer to create a precise spatial representation – even down to the level of individual atoms," explains Professor Mücklich.

In their search for more robust materials, the research team also used laser cladding to deposit microscopic layers of different materials onto the titanium contacts. They also employed laser interference structuring techniques to modify the surface of the clamps in an effort to make them more robust. While these techniques certainly improved the properties of the original titanium, the improvements were not sufficient to permanently withstand the enormous stresses to which the clamps are subjected during the PCB electroplating process. "This led us to the idea of using copper as a sacrificial layer that can be continuously replenished during the PCB production process. The advantages of this approach are that copper is far cheaper than the other materials that had been tested and that it was already present in the system. It was this that ultimately led to the successful conclusion of the research project," explains Frank Mücklich. In recognition of their efforts, Professor Mücklich, together with research assistants Dominik Britz and Christian Selzner and the project members from Atotech, will receive the Transfer Award, which is conferred by the Steinbeis Foundation and worth up to 60,000 euros, at a ceremony in Stuttgart.

INFORMATION:

Background: The Steinbeis Foundation's Transfer Award

The Steinbeis Transfer Award is conferred for outstanding projects involving the successful transfer of competitively relevant knowledge and technology between science and industry. Transfer projects that have shown excellence in execution and have been completed successfully are considered particularly worthy of the award.

The Steinbeis Foundation for Economic Development with headquarters in Stuttgart provides support to research scientists to facilitate the transfer of their research results to industry. The 900 Steinbeis Centres that have been established in Germany and around the world form the Steinbeis Network that links knowledge and technology transfer centres, research centres and consulting and advisory centres across a very broad range of disciplines. The Steinbeis Foundation provides support to academic researchers looking to successfully transfer knowledge and technology into the industrial sector. The Steinbeis Foundation has been a Saarland University cooperation partner since 2002.

Press photographs can be downloaded at: www.uni-saarland.de/pressefotos

For further information, please visit:

www.uni-saarland.de/fuwe

www.mec-s.de

www.atotech.com/de

www.stw.de/wir-ueber-uns/loehn-preis

Questions can be addressed to:

Prof. Dr. Frank Mücklich

Chair of Functional Materials at Saarland University

Steinbeis-Research Center – Material Engineering Center Saarland (MECS)

Tel.: +49 (0)681 302-70500

Mail: muecke@matsci.uni-sb.de

Materials scientists prevent wear in production facilities in the electronics industry

2012-10-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

HIV helps explain rise of anal cancer in US males

2012-10-06

The increase in anal cancer incidence in the U.S. between 1980 and 2005 was greatly influenced by HIV infections in males, but not females, according to a study published October 5 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Anal cancer in the U.S. is rare, with an estimated 6,230 cases in 2012, but incidence has been steadily increasing in the general population since 1940. HIV infection is significantly associated with an increase in anal cancer risk, and anal cancer is the fourth most common cancer found in HIV-infected people. However, it has been unclear the ...

HIV drug shows efficacy in treating mouse models of HER2+ breast cancer

2012-10-06

The HIV protease inhibitor, Nelfinavir, can be used to treat HER2-positive breast cancer in the same capacity and dosage regimen that it is used to treat HIV, according to a study published October 5 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Breast cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer deaths in the U.S. with approximately 39,520 women succumbing to the disease in 2011. HER2-postive breast cancer is known to be more aggressive and less responsive to treatments compared to other types of breast cancer. Nelfinavir has been shown to inhibit the growth ...

Superheroes needed to tackle timebomb of public health challenges

2012-10-06

Public health 'superheroes' are needed to help tackle the growing challenges posed by obesity, alcohol, smoking and other public health threats, according to new research published today.

The research, an international collaboration from the Universities of Leeds, Alberta and Wisconsin, calls for government and policy makers to recognise the role that public health leaders can play in addressing these significant health challenges.

It suggests that potential public health 'superheroes' can come from both within public health disciplines, and perhaps more importantly, ...

Whether we like someone affects how our brain processes movement

2012-10-06

Hate the Lakers? Do the Celtics make you want to hurl? Whether you like someone can affect how your brain processes their actions, according to new research from the Brain and Creativity Institute at USC.

Most of the time, watching someone else move causes a 'mirroring' effect – that is, the parts of our brains responsible for motor skills are activated by watching someone else in action.

But a study by USC researchers appearing Oct. 5 in PLOS ONE shows that whether or not you like the person you're watching can actually have an effect on brain activity related to ...

Testing can be useful for students and teachers, promoting long-term learning

2012-10-06

Pop quiz! Tests are good for: (a) Assessing what you've learned; (b) Learning new information; (c) a & b; (d) None of the above.

The correct answer?

According to research from psychological science, it's both (a) and (b) – while testing can be useful as an assessment tool, the actual process of taking a test can also help us to learn and retain new information over the long term and apply it across different contexts.

New research published in journals of the Association for Psychological Science explores the nuanced interactions between testing, memory, and learning ...

Mount Sinai researchers find mechanism of opiate addiction is completely different from other drugs

2012-10-06

Chronic morphine exposure has the opposite effect on the brain compared to cocaine in mice, providing new insight into the basis of opiate addiction, according to Mount Sinai School of Medicine researchers. They found that a protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is increased in cocaine addiction, is inhibited in opioid addiction. The research is published in the October 5 issue of Science.

"Our study shows that BDNF responds completely differently with opioid administration compared to cocaine," said Ja Wook Koo, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow in ...

Methadone reduces the risk of HIV transmission

2012-10-06

This press release is available in French.

Methadone reduces the risk of HIV transmission in people who inject drugs (PWID), as reported by an international team of researchers in a paper published today in the online edition of the British Medical Journal. This team included Dr. Julie Bruneau from the CHUM Research Centre (CRCHUM) and the Department of Family Medicine at the Université de Montréal.

"There is good evidence to suggest that opiate substitution therapies (OST) reduce drug-related mortality, morbidity and some of the injection risk behaviors among PWID. ...

NASA's Swift satellite discovers a new black hole in our galaxy

2012-10-06

WASHINGTON -- NASA's Swift satellite recently detected a rising tide of high-energy X-rays from a source toward the center of our Milky Way galaxy. The outburst, produced by a rare X-ray nova, announced the presence of a previously unknown stellar-mass black hole.

"Bright X-ray novae are so rare that they're essentially once-a-mission events and this is the first one Swift has seen," said Neil Gehrels, the mission's principal investigator, at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "This is really something we've been waiting for."

An X-ray nova is a short-lived ...

Sun spits out a coronal mass ejection

2012-10-06

At 11:24 p.m. EDT on Oct. 4, 2012, the sun unleashed a coronal mass ejection (CME). Not to be confused with a solar flare, which is a burst of light and radiation, CMEs are a phenomenon that can send solar particles into space and can reach Earth one to three days later. Experimental NASA research models show the CME to be traveling at about 400 miles per second.

When Earth-directed, CMEs can affect electronic systems in satellites and on Earth. CMEs of this speed, however, have not generally caused major effects in the past. Further updates will be provided if needed.INFORMATION:

NOAA's ...

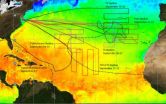

NASA's HS3 mission thoroughly investigates long-lived Hurricane Nadine

2012-10-06

NASA's Hurricane and Severe Storm Sentinel or HS3 scientists had a fascinating tropical cyclone to study in long-lived Hurricane Nadine. NASA's Global Hawk aircraft has investigated Nadine five times during the storm's lifetime.

NASA's Global Hawk also circled around the eastern side of Hurricane Leslie when it initially flew from NASA's Dryden Research Flight Center, Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. to the HS3 base at NASA's Wallops Flight Facility, Wallops Island, Va. on Sept. 6-7, 2012.

Nadine has been a great tropical cyclone to study because it has lived so long ...