(Press-News.org) Three studies conducted as part of Wayne State University's Systems Biology of Epilepsy Project (SBEP) could result in new types of treatment for the disease and, as a bonus, for behavioral disorders as well.

The SBEP started out with funds from the President's Research Enhancement Fund and spanned neurology, neuroscience, genetics and computational biology. It since has been supported by multiple National Institutes of Health-funded grants aimed at identifying the underlying causes of epilepsy, and it is uniquely integrated within the Comprehensive Epilepsy Program at the Wayne State School of Medicine and the Detroit Medical Center.

Under the guidance of Jeffrey Loeb, M.D., Ph.D., associate director of the Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics (CMMG) and professor of neurology, the project brings together researchers from different fields to create an interdisciplinary research program that targets the complex disease. The multifaceted program at Wayne State is like no other in the world, officials say, with two primary goals: improving clinical care and creating novel strategies for diagnosis and treatment of patients with epilepsy.

The three studies were published in high-impact journals and use human brain tissue research to identify new targets for drug development, generate a new animal model and identify a new class of drugs to treat the disease.

In the first study, "Layer-Specific CREB Target Gene Induction in Human Neocortical Epilepsy," published recently in the Journal of Neuroscience, donated human brain samples were probed to identify 137 genes strongly associated with epileptic seizures.

Researchers then showed that the most common pathway is activated in very specific layers of the cortex, and that it's associated with increased numbers of synapses in those areas. Because epilepsy is a disease of abnormal neuronal synchrony, the finding could explain why some brain regions produce clinical seizures.

"Higher density of synapses may explain how abnormal epileptic discharges, or spikes, are formed, and in what layer," Loeb said, adding that localizing the exact layer of the brain in which that process occurs is useful both for understanding the mechanism and for developing therapeutics.

The first study, which identified a new drug target for epilepsy, precipitated a second study that has found such a drug.

In the second study, "Electrical, Molecular and Behavioral Effects of Interictal Spiking in the Rat," published recently in Neurobiology of Disease, SBEP researchers found that the same brain layers in the rat are activated as in the human tissues and searched for a drug to target those layers. In fact, the first drug they tried, a compound called SL327 that has been used in nonhuman subjects to understand how memory works, "worked like a dream," Loeb said.

"SL327 prevented spiking in rat brains," he said, "which not only prevented seizures, but led to more normal behaviors as well."

That finding led to collaborations between Loeb's lab and Nash Boutros, M.D., professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences, and the Belgian drug company UCB.

"Whereas animals that developed epileptic spiking became hyperactive, those treated with the drug and had less spiking in their brains were more like normal animals," Loeb said. "Now whenever we screen for drugs for epilepsy, we look at behavior as well as epileptic activity."

Noting that many seizure medicines currently are used to treat various psychiatric disorders, Loeb said the SBEP team's latest round of work marks a "nice crossover" between psychiatry and neurology in the field of drugs related to epilepsy.

In the third study, just published in Genetics, researchers say they have found "fascinating interrelationships" between "junk" long noncoding RNA and normal RNA that are regulated by human brain activity. That work has the potential to be translated into new genetic treatments for epilepsy.

"This study shows how the human brain deals with half of the human genome in its most important function, electrical activity, using human brain tissue from patients with epilepsy to understand the basic molecular processes of how the brain works, and what's unique about human brains compared to the brains of less-developed species," Loeb said.

The third study, titled "Activity-Dependent Human Brain Coding/Noncoding Gene Regulatory Networks," is a collaborative effort between Loeb's lab and Leonard Lipovich, Ph.D., assistant professor of neurology and molecular medicine and genetics. It found that certain genes and their noncoding counterparts (which some researchers have called "junk") are co-regulated, or turned on at the same time, with brain activity.

"This tells us that some of these noncoding genes may actually have functions in brain activity," Loeb said. "In some, turning one on turns another one off. Some are regulatory and can be used to control plasticity genes — which are involved in memory, learning and behavior — with one of these novel, noncoding RNA genes."

The synergy exhibited by the three studies, Loeb said, is testimony to the multidisciplinary nature of Wayne State's systems biology platform, partly developed with a remarkable three-dimensional database created in cooperation with Farshad Fotouhi, Ph.D., dean of the College of Engineering, and Jing Hua, Ph.D., associate professor of computer science.

"SBEP is a cross-campus endeavor," Loeb said. "These studies are the fruits of the labor of this consortium and only exist at WSU. The next steps will be translating these exciting findings into new treatments to prevent or even cure patients with epilepsy and other psychiatric disorders."

###

The above studies were funded by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant Nos. R01NS045207, R01Ns05058802, F30NS049776; by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the NIH, grant No. 1R03DA0262-01; and by the State of Michigan Joe Young Funds to the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, and were started with help from the WSU President's Research Enhancement Fund.

Wayne State University is one of the nation's pre-eminent public research universities in an urban setting. Through its multidisciplinary approach to research and education, and its ongoing collaboration with government, industry and other institutions, the university seeks to enhance economic growth and improve the quality of life in the city of Detroit, state of Michigan and throughout the world. For more information about research at Wayne State University, visit http://www.research.wayne.edu.

New treatments for epilepsy, behavioral disorders could result from Wayne State studies

2012-10-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Safety results of intra-arterial stem cell clinical trial for stroke presented

2012-10-12

HOUSTON – (Oct. 11, 2012) – Early results of a Phase II intra-arterial stem cell trial for ischemic stroke showed no adverse events associated with the first 10 patients, allowing investigators to expand the study to a targeted total of 100 patients.

The results were presented today by Sean Savitz, M.D., professor of neurology and director of the Stroke Program at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), at the 8th World Stroke Congress in Brasilia, Brazil.

The trial is the only randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled intra-arterial clinical ...

Satellite sees 16th Atlantic tropical depression born near Bahamas

2012-10-12

The 16th tropical depression of the Atlantic Ocean season has formed northeast of the Bahamas and NOAA's GOES-14 satellite captured a visible image of the storm as it tracks to the southwest.

NOAA's GOES-14 satellite captured a visible image of newborn Tropical Depression 16 (TD16) near the Bahamas on Oct. 11 at 7:45 a.m. EDT. TD16 appeared as a rounded area of clouds just northeast of the Bahamas and its western fringes were just off the Florida east coast. GOES-14 also showed another low pressure area with the potential for development a few hundred miles from the Windward ...

NASA sees Typhoon Prapiroon doing a 'Sit and Spin' in the Philippine Sea

2012-10-12

As Typhoon Prapiroon slowed down and became quasi-stationary in the Philippine Sea NASA's Terra satellite passed overhead and captured an image of the storm.

NASA's Terra satellite passed over Typhoon Prapiroon on Oct. 11 at 0210 UTC (1010 p.m. EDT, Oct. 10) and the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument captured a visible image of the storm. The visible imagery clearly showed a small ragged eye, and microwave satellite imagery confirmed the eye. Satellite imagery also confirmed a well-defined low-level center of circulation.

By 11 a.m. EDT ...

Nurture trumps nature in study of oral bacteria in human twins, says CU study

2012-10-12

A new long-term study of human twins by University of Colorado Boulder researchers indicates the makeup of the population of bacteria bathing in their saliva is driven more by environmental factors than heritability.

The study compares saliva samples from identical and fraternal twins to see how much "bacterial communities" in saliva vary from mouth to mouth at different points in time, said study leader and CU-Boulder Professor Kenneth Krauter. The twin studies show that the environment, rather than a person's genetic background, is more important in determining the ...

When galaxies eat galaxies

2012-10-12

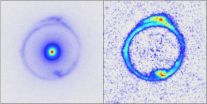

SALT LAKE CITY, Oct. 11, 2012 – Using gravitational "lenses" in space, University of Utah astronomers discovered that the centers of the biggest galaxies are growing denser – evidence of repeated collisions and mergers by massive galaxies with 100 billion stars.

"We found that during the last 6 billion years, the matter that makes up massive elliptical galaxies is getting more concentrated toward the centers of those galaxies. This is evidence that big galaxies are crashing into other big galaxies to make even bigger galaxies," says astronomer Adam Bolton, principal ...

Exposure to traffic air pollution in infancy impairs lung function in children

2012-10-12

Exposure to ambient air pollution from traffic during infancy is associated with lung function deficits in children up to eight years of age, particularly among children sensitized to common allergens, according to a new study.

"Earlier studies have shown that children are highly susceptible to the adverse effects of air pollution and suggest that exposure early in life may be particularly harmful," said researcher Göran Pershagen, MD, PhD, professor at the Karolinska Institutet Institute of Environmental Medicine in Stockholm, Sweden. "In our prospective birth cohort ...

Quiz, already used in elderly, could determine death risk for kidney dialysis patients of all ages

2012-10-12

A simple six-question quiz, typically used to assess disabilities in the elderly, could help doctors determine which kidney dialysis patients of any age are at the greatest risk of death, new Johns Hopkins research suggests.

Believing that kidney failure mimics an accelerated body-wide aging process transplant surgeon Dorry L. Segev, M.D., Ph.D., and his colleagues turned to geriatric experts to examine mortality risk in patients undergoing dialysis. They found that those who needed assistance with one or more basic activities of daily living – feeding, dressing, walking, ...

Integrative Psychiatrist Richard P. Brown Teaches Drug Free Approaches for ADD/ADHD to Therapists at New York Open Center, Manhattan

2012-10-12

Richard P. Brown, MD, a psychopharmacologist who integrates CAM (Complimentary and Alternative Medicine) into his treatments, will present an evening workshop on Friday, October 12, 2012, from 7 to 10 pm, at The New York Open Center, 22 E. 30th Street, New York, NY, 10016, entitled "Drug Free Approaches to Treating ADD/ADHD," for psychotherapists looking to complement their practices with herbs, nutrients, and mind-body techniques.

Dr. Richard P. Brown will share up-to-date information about a range of treatments for children and adults with Attention Deficit ...

Innovative Results Boot Camp Raises Over $2500 for Children's Charity

2012-10-12

Innovative Results has teamed up with Compassion International and The Crossing church to use the profits from their Saturday morning Orange County boot camps to make a positive difference in the lives of needy children and their families.

Innovative Results began holding their fundraising _a href="http://www.innovative-results.com/orange-county-fitness-boot-camps/"_Orange County boot camp_/a_ in May of 2012. Since then, Innovative Results has raised over $2500.00 to provide assistance not only to local families, but also to impoverished children and families ...

Breast Cancer Survivors' Workshop

2012-10-12

Breast Cancer Survivors travel a challenging path - whether it is worrying about the survival rates of breast cancer, or how to tailor the diet to best take care of your health during and after cancer treatment. PCC is here to address doubts and questions to post breast cancer treatment and how to take control of your health. Take part in Parkway Cancer Centre Breast Cancer Survivor's Workshop with doctors and experts on 13th October 2012.

Details are as follows:

Date: Saturday, 13th October 2012

Venue: Topaz Ballroom, Sheraton Towers

Time: 1.00pm - 6.00pm

Programme ...