(Press-News.org) Neutron scattering experiments have provided new insights into the origin of the side effects of an antifungal drug prescribed all over the world. The analysis conducted by scientists at King's College London and the Institut Laue-Langevin in Grenoble, and published in Scientific Reports, follows 40 years of debate and could help drug developers reduce these harmful complications.

Wherever you are in the world, indoors or outdoors, the air you breathe contains fungal spores. Though occasionally linked with allergies, asthma or skin irritations, the majority are easily dealt with by the body's immune system.

A far greater risk is posed to individuals whose immune systems are already compromised such as those infected with HIV, severe burn victims or those having just undergone chemotherapy.

Treatment with AmB

The most successful treatment to date is an antibiotic first developed in the 1950s called Amphotericin B (AmB) which was shown to attack fungal cells. The drug is highly effective. Mortality rates associated with these types of fungal infections in vulnerable patients are about 80% without treatment, yet fall below 30% when treated with AmB.

However in the past 20 years there has been a dramatic rise in cases of the fungi developing antibiotic resistance. This has necessitated the prescription of increased doses of AmB which unexpectedly produced severe and sometimes lethal side effects. Tests have shown that at these heightened doses nearly 50% of patients suffer from some form of kidney poisoning. In one study 15% of patients on the drug were forced to go on kidney dialysis. In less common cases AmB can even lead to complete failure of the kidneys, liver or even the heart.

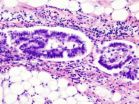

The accepted explanation of AmB as an antibiotic has been that it combines with molecules found in the membrane to create barrel shaped holes which allow cell material to leak out or harmful material to get in, killing the cell.

Whilst fungal membranes contain called ergosterol, animal cell membranes, including our own, contain the more familiar cholesterol. It is thought that AmB reacts more readily with ergosterol to form these membrane holes than it does with cholesterol. This would explain why at low doses AmB can be used to treat infection without harming the patient, however there has so far been no direct evidence to support this hypothesis.

Structural analysis by neutron diffraction at the ILL

In this new paper, Dr David Barlow and his colleagues from King's College London describe neutron diffraction experiments at the Institut Laue-Langevin, the flag-ship centre for neutron science that reveal how AmB interacts with fungal and animal cell membranes on sub-molecular scales of around 1 millionth the width of a human hair.

Like all particles, neutrons demonstrate some wave like behaviour, and when they encounter obstacles whose size is comparable with their wavelength they scatter along well-defined angles. It is this property which allows scientists at neutron sources such as the ILL to analyse the scattering patterns and infer the structure of the material the neutrons have passed through.

The team modelled the two different membranes with layers of lipids, fatty molecules found in all cells, which were combined with either cholesterol or ergosterol. The team used deuteration techniques where deuterium, a heavier isotope of hydrogen which is easily picked out by neutrons over its lighter cousin, is introduced to either the membrane model or the drug, tagging that part of the system to follow it during the interaction.

The results

Using these techniques the team unveiled the first experimental evidence for the theoretical 'leaky holes' resulting from the development of 'barrel-like' structures which formed in both membranes upon the introduction of AmB.

However, the barrels were found to penetrate more deeply into the fungal membranes than the human membranes at the same relatively low dose. The implication is that at such low doses during treatment, the AmB can open up holes in fungal cells but is unable to do so as readily in the human cells. Only when the dose is increased do you get holes passing right across both types of membranes and the resulting damage to healthy tissue.

The underlying cause of this difference in membrane insertion may be down to differences in the angle of insertion, identified for the first time in this paper. When the AmB inserts into the fungal (ergosterol-containing) membranes, it appears to be less tilted than when it inserts into the human (cholesterol-containing) membranes.

The next step for Dr Barlow is to improve the resolution of the analysis in order to identify the exact part of the drug which forms these barrel structures. It is this part that drug developers would need to play with to improve AmB's specificity to fungal cells, or use to develop a whole new drug with less harmful side effects.

Dr David Barlow from King's said: 'These are particularly harmful and potentially lethal side effects. The problem is, despite being developed in the 50's, no-one up until now has been able to experimentally determine how AmB works. This is vital if we are to reduce its complications or use its therapeutic properties in new less harmful, drugs.'

Dr Bruno Demé, a scientist at the ILL who worked with Dr Barlow on ILL's D16 neutron diffraction instrument said; 'Neutrons are an ideal tool for studying biological materials and their behaviour as proteins, viruses and cell membranes, all of the order of 1 to 10 nanometres, easily fall within the right size scale. Also neutrons are particularly sensitive to lighter atoms such as carbon, hydrogen and oxygen that make up these organic molecules and can distinguish between them very easily. With the world most powerful source of neutrons in the world, the ILL has a long history of significant breakthroughs in understanding and improving drug delivery and treatment mechanisms.'

INFORMATION:

CONTACT

James Romero

Proof Communication

Tel: +44 845 680 1866

Email: james@proofcommunication.com

NOTES TO EDITORS

Neutron diffraction studies of the interaction between amphotericin B and lipid-sterol model membranes

Scientific Reports, Published 29 October 2012; DOI: 10.1038/srep00778

Paper and images available on request

The Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL) is an international research centre based in Grenoble, France. It has led the world in neutron-scattering science and technology for almost 40 years, since experiments began in 1972. ILL operates one of the most intense neutron sources in the world, feeding beams of neutrons to a suite of 40 high-performance instruments that are constantly upgraded. Each year 1,200 researchers from over 40 countries visit ILL to conduct research into condensed matter physics, (green) chemistry, biology, nuclear physics, and materials science. The UK, along with France and Germany is an associate and major funder of the ILL.

King's College London (www.kcl.ac.uk) is one of the top 30 universities in the world (2012/13 QS international world rankings), and was The Sunday Times 'University of the Year 2010/11', and the fourth oldest in England. A research-led university based in the heart of London, King's has more than 24,000 students (of whom more than 10,000 are graduate students) from nearly 140 countries, and more than 6,100 employees. King's is in the second phase of a £1 billion redevelopment programme which is transforming its estate.

King's has an outstanding reputation for providing world-class teaching and cutting-edge research. In the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise for British universities, 23 departments were ranked in the top quartile of British universities; over half of our academic staff work in departments that are in the top 10 per cent in the UK in their field and can thus be classed as world leading. The College is in the top seven UK universities for research earnings and has an overall annual income of nearly £525 million (year ending 31 July 2011).

King's has a particularly distinguished reputation in the humanities, law, the sciences (including a wide range of health areas such as psychiatry, medicine, nursing and dentistry) and social sciences including international affairs. It has played a major role in many of the advances that have shaped modern life, such as the discovery of the structure of DNA and research that led to the development of radio, television, mobile phones and radar.

King's College London and Guy's and St Thomas', King's College Hospital and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trusts are part of King's Health Partners. King's Health Partners Academic Health Sciences Centre (AHSC) is a pioneering global collaboration between one of the world's leading research-led universities and three of London's most successful NHS Foundation Trusts, including leading teaching hospitals and comprehensive mental health services. For more information, visit: www.kingshealthpartners.org.

Neutrons help explain why antibiotics prescribed for chemotherapy cause kidney failure

Analysis will help development of new treatments to protect vulnerable patients undergoing chemotherapy or suffering from HIV

2012-10-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists decode 'software' instructions of aggressive leukemia cells

2012-10-29

NEW YORK (Oct. 28, 2012) -- A team of national and international researchers, led by Weill Cornell Medical College scientists, have decoded the key "software" instructions that drive three of the most virulent forms of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). They discovered ALL's "software" is encoded with epigenetic marks, chemical modifications of DNA and surrounding proteins, allowing the research team to identify new potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

The research, published in Cancer Discovery, is the first study to show how these three different forms of ...

Research provides new insights into dogs' natural feeding behavior and finds they target a daily dietary intake that is high in fat

2012-10-29

An international team of researchers has shed new light on the natural feeding behaviour of domestic dogs and demonstrated that they will naturally seek a daily dietary intake that is high in fat. The study also showed that some dogs will overeat if given excess food, reinforcing the importance of responsible feeding to help ensure dogs maintain a healthy body weight.

The research was conducted by the WALTHAM® Centre for Pet Nutrition – the science centre underpinning Mars Petcare brands such as PEDIGREE®, NUTRO® and ROYAL CANIN. It was undertaken in collaboration with ...

Increased risk for breast cancer death among black women greatest during first 3 years postdiagnosis

2012-10-29

SAN DIEGO — Non-Hispanic black women diagnosed with breast cancer, specifically those with estrogen receptor-positive tumors, are at a significantly increased risk for breast cancer death compared with non-Hispanic white women.

"This difference was greatest in the first three years after diagnosis," said Erica Warner, M.P.H., Sc.D., a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard School of Public Health in Boston, Mass., who presented the data at the Fifth AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities, held here Oct. 27-30, 2012.

Prior research has shown that non-Hispanic ...

Black patients received less clinical trial information than white patients

2012-10-29

SAN DIEGO — A study comparing how physicians discuss clinical trials during clinical interactions with black patients versus white patients further confirms racial disparities in the quality of communication between physicians and patients.

Oncologists provided black patients with less information overall about cancer clinical trials compared with white patients, according to data presented at the Fifth AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities, held here Oct. 27-30, 2012.

"Minority patients tend to receive less information, which could, in part, ...

Women in less affluent areas of Chicago less likely to reside near mammography facility

2012-10-29

SAN DIEGO — Women in socioeconomically disadvantaged and less affluent areas of Chicago were less likely to live near a mammography facility with various aspects of care compared with women in less socioeconomically disadvantaged and more affluent areas. This finding could be a contributing factor to the association between disadvantaged areas and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis, according to data presented at the Fifth AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities, held here Oct. 27-30, 2012.

"Other research has found that women living in disadvantaged ...

Associations linking weight to breast cancer survival vary by race/ethnicity

2012-10-29

SAN DIEGO — An extreme body mass index or high waist-to-hip ratio, both measures of body fat, increased risk for mortality among patients with breast cancer, but this association varied by race/ethnicity, according to recently presented data.

Marilyn L. Kwan, Ph.D., a research scientist in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research in Oakland, Calif., presented these results at the Fifth AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities, held here Oct. 27-30, 2012.

Prior research has shown racial/ethnic differences in survival after a ...

Minorities most likely to have aggressive tumors, less likely to get radiation

2012-10-29

SAN DIEGO — Women with aggressive breast cancer were more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy, but at the expense of completing locoregional radiation therapy, according to recently presented data. This was especially true in minorities, who were the most likely to present with moderate- to high-grade and symptomatically detected tumors.

"Radiation treatment decreases the risk for breast cancer recurring and improves survival from the disease," said Abigail Silva, M.P.H., Susan G. Komen Cancer Disparities Research trainee at the University of Illinois in Chicago, ...

Language, immigration status of hispanic caregivers impacted care of children with cancer

2012-10-29

SAN DIEGO — Language barriers and the immigration status of caregivers appear to impact the care of Hispanic children with cancer and affect the experience of the families within the medical system, according to data presented at the Fifth AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities, held here Oct. 27-30, 2012.

"Ensuring good communication with patients and their families is as important as the actual therapy we give, regardless of what language is spoken," said Mark Fluchel, M.D., assistant professor in the department of pediatrics, division of hematology-oncology ...

Researchers look beyond space and time to cope with quantum theory

2012-10-29

Physicists have proposed an experiment that could force us to make a choice between extremes to describe the behaviour of the Universe.

The proposal comes from an international team of researchers from Switzerland, Belgium, Spain and Singapore, and is published today in Nature Physics. It is based on what the researchers call a 'hidden influence inequality'. This exposes how quantum predictions challenge our best understanding about the nature of space and time, Einstein's theory of relativity.

"We are interested in whether we can explain the funky phenomena we observe ...

NIH researchers identify novel genes that may drive rare, aggressive form of uterine cancer

2012-10-29

Researchers have identified several genes that are linked to one of the most lethal forms of uterine cancer, serous endometrial cancer. The researchers describe how three of the genes found in the study are frequently altered in the disease, suggesting that the genes drive the development of tumors. The findings appear in the Oct. 28, 2012, advance online issue of Nature Genetics. The team was led by researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), part of the National Institutes of Health.

Cancer of the uterine lining, or endometrium, is the most ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Paleontologist Stephen Chester and colleagues reveal new clues about early primate evolution

UF research finds a gentler way to treat aggressive gum disease

Strong alcohol policy could reduce cancer in Canada

Air pollution from wildfires linked to higher rate of stroke

Tiny flows, big insights: microfluidics system boosts super-resolution microscopy

Pennington Biomedical researcher publishes editorial in leading American Heart Association journal

New tool reveals the secrets of HIV-infected cells

HMH scientists calculate breathing-brain wave rhythms in deepest sleep

Electron microscopy shows ‘mouse bite’ defects in semiconductors

Ochsner Children's CEO joins Make-A-Wish Board

Research spotlight: Exploring the neural basis of visual imagination

Wildlife imaging shows that AI models aren’t as smart as we think

Prolonged drought linked to instability in key nitrogen-cycling microbes in Connecticut salt marsh

Self-cleaning fuel cells? Researchers reveal steam-powered fix for ‘sulfur poisoning’

Bacteria found in mouth and gut may help protect against severe peanut allergic reactions

Ultra-processed foods in preschool years associated with behavioural difficulties in childhood

A fanged frog long thought to be one species is revealing itself to be several

Weill Cornell Medicine selected for Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award

Largest high-precision 3D facial database built in China, enabling more lifelike digital humans

SwRI upgrades facilities to expand subsurface safety valve testing to new application

Iron deficiency blocks the growth of young pancreatic cells

Selective forest thinning in the eastern Cascades supports both snowpack and wildfire resilience

A sea of light: HETDEX astronomers reveal hidden structures in the young universe

Some young gamers may be at higher risk of mental health problems, but family and school support can help

Reduce rust by dumping your wok twice, and other kitchen tips

High-fat diet accelerates breast cancer tumor growth and invasion

Leveraging AI models, neuroscientists parse canary songs to better understand human speech

Ultraprocessed food consumption and behavioral outcomes in Canadian children

The ISSCR honors Dr. Kyle M. Loh with the 2026 Early Career Impact Award for Transformative Advances in Stem Cell Biology

The ISSCR honors Alexander Meissner with the 2026 ISSCR Momentum Award for exceptional work in developmental and stem cell epigenetics

[Press-News.org] Neutrons help explain why antibiotics prescribed for chemotherapy cause kidney failureAnalysis will help development of new treatments to protect vulnerable patients undergoing chemotherapy or suffering from HIV