(Press-News.org) China's endangered wild pandas may need new dinner reservations – and quickly – based on models that indicate climate change may kill off swaths of bamboo that pandas need to survive.

In this week's international journal Nature Climate Change, scientists from Michigan State University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences give comprehensive forecasts of how changing climate may affect the most common species of bamboo that carpet the forest floors of prime panda habitat in northwestern China. Even the most optimistic scenarios show that bamboo die-offs would effectively cause prime panda habitat to become inhospitable by the end of the 21st century.

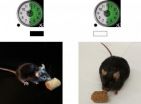

The scientists studied possible scenarios of climate change in the Qinling Mountains in ShaanxiProvince. At the northern boundary of China's panda distributional range, the Qinling Mountains are home to around 275 wild pandas, about 17 percent of the remaining wild population. The Qinling pandas have been isolated due to the thousands-year history of human habitation around the mountain range. They vary genetically from other giant pandas -- some have a more brownish color -- and their geographic isolation makes it particularly valuable for conservation, but vulnerable to climate change.

"Understanding impacts of climate change is an important way for science to assist in making good decisions," said Jianguo "Jack" Liu, director of MSU's Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability (CSIS) and a study co-author. "Looking at the climate impact on the bamboo can help us prepare for the challenges that the panda will likely face in the future."

Bamboo is a vital part of forest ecosystems, being not only the sole menu item for giant pandas, but also providing essential food and shelter for other wildlife, including other endangered species like the ploughshare tortoise and purple-winged ground-dove. Bamboo can be a risky crop to stake survival on, with an unusual reproductive cycle. The species studied only flower and reproduce every 30 to 35 years, which limits the plants' ability to adapt to changing climate and can spell disaster for a food supply.

Mao-Ning Tuanmu, who recently finished his PhD studies at CSIS, and colleagues constructed unique models, using field data on bamboo locality, multiple climate projections and historic data of precipitation and temperature ranges and greenhouse gas emission scenarios to evaluate how three dominant bamboo species would fare in the Qinling Mountains of China.

Not many scientists to date have studied understory bamboo, Tuanmu said. But evidence found in fossil and pollen records does indicate that over time bamboo distribution has followed the benefits – and devastation – of climate change.

Pandas' fate will be at the hands of not only nature, but also humans. If, as the study's models predict, large swaths of bamboo become unavailable, human development prevents pandas from a clear, accessible path to the next meal source.

"The giant panda population also is threatened by other human disturbances, Tuanmu said. "Climate change is only one challenge for the giant pandas. But on the other hand, the giant panda is a special species. People put a lot of conservation resources in to them compared to other species. We want to provide data to guide that wisely."

The models can point the way for proactive planning to protect areas that have a better climatic chance of providing adequate food sources, or begin creating natural "bridges" to allow pandas an escape hatch from bamboo famine.

"We will need proactive actions to protect the current giant panda habitats," Tuanmu said. "We need time to look at areas that might become panda habitat in the future, and to think now about maintaining connectivity of areas of good panda habitat and habitat for other species. What will be needed is speed."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Tuanmu, who now is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale University, the paper "Climate change impacts on understory bamboo species and giant pandas in China's Qinling Mountains" was authored by Andrés Viña, assistant professor of fisheries and wildlife and a CSIS member; Julie Winkler, MSU geography professor; Yu Li, a research assistant and CSIS alumnus, and Zhiyun Ouyang and Weihua Xu, director and associate professor of the State Key Laboratory of Urban and Regional Ecology, Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The research was funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation, as well as support by MSU AgBioResearch.

Climate change threatens giant pandas' bamboo buffet – and survival

2012-11-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

It's not just what you eat, but when you eat it

2012-11-12

PHILADELPHIA - Fat cells store excess energy and signal these levels to the brain. In a new study this week in Nature Medicine, Georgios Paschos PhD, a research associate in the lab of Garret FitzGerald, MD, FRS director of the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, shows that deletion of the clock gene Arntl, also known as Bmal1, in fat cells, causes mice to become obese, with a shift in the timing of when this nocturnal species normally eats. These findings shed light on the complex causes of obesity ...

Using rust and water to store solar energy as hydrogen

2012-11-12

How can solar energy be stored so that it can be available any time, day or night, when the sun shining or not? EPFL scientists are developing a technology that can transform light energy into a clean fuel that has a neutral carbon footprint: hydrogen. The basic ingredients of the recipe are water and metal oxides, such as iron oxide, better known as rust. Kevin Sivula and his colleagues purposefully limited themselves to inexpensive materials and easily scalable production processes in order to enable an economically viable method for solar hydrogen production. The device, ...

A better brain implant: Slim electrode cozies up to single neurons

2012-11-12

ANN ARBOR—A thin, flexible electrode developed at the University of Michigan is 10 times smaller than the nearest competition and could make long-term measurements of neural activity practical at last.

This kind of technology could eventually be used to send signals to prosthetic limbs, overcoming inflammation larger electrodes cause that damages both the brain and the electrodes.

The main problem that neurons have with electrodes is that they make terrible neighbors. In addition to being enormous compared to the neurons, they are stiff and tend to rub nearby cells ...

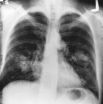

Gene variations linked to lung cancer susceptibility in Asian women

2012-11-12

An international group of scientists has identified three genetic regions that predispose Asian women who have never smoked to lung cancer. The finding provides further evidence that risk of lung cancer among never-smokers, especially Asian women, may be associated with certain unique inherited genetic characteristics that distinguishes it from lung cancer in smokers.

Lung cancer in never-smokers is the seventh leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, and the majority of lung cancers diagnosed historically among women in Eastern Asia have been in women who never smoked. ...

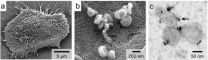

Detection, analysis of 'cell dust' may allow diagnosis, monitoring of brain cancer

2012-11-12

A novel miniature diagnostic platform using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology is capable of detecting minuscule cell particles known as microvesicles in a drop of blood. Microvesicles shed by cancer cells are even more numerous than those released by normal cells, so detecting them could prove a simple means for diagnosing cancer. In a study published in Nature Medicine, investigators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Systems Biology (CSB) demonstrate that microvesicles shed by brain cancer cells can be reliably detected in human blood through ...

Researchers discover 2 genetic flaws behind common form of inherited muscular dystrophy

2012-11-12

SEATTLE – An international research team co-led by a scientist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center has identified two genetic factors behind the third most common form of muscular dystrophy. The findings, published online in Nature Genetics, represent the latest in the team's series of groundbreaking discoveries begun in 2010 regarding the genetic causes of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, or FSHD.

The team, co-led by Stephen Tapscott, M.D., Ph.D., a member of the Hutchinson Center's Human Biology Division, discovered that a rare variant of FSHD, called type ...

Touch-sensitive plastic skin heals itself

2012-11-12

Nobody knows the remarkable properties of human skin like the researchers struggling to emulate it. Not only is our skin sensitive, sending the brain precise information about pressure and temperature, but it also heals efficiently to preserve a protective barrier against the world. Combining these two features in a single synthetic material presented an exciting challenge for Stanford Chemical Engineering Professor Zhenan Bao and her team.

Now, they have succeeded in making the first material that can both sense subtle pressure and heal itself when torn or cut. Their ...

36 in one fell swoop -- researchers observe 'impossible' ionization

2012-11-12

This press release is available in German.

Using the world's most powerful X-ray laser in California, an international research team discovered a surprising behaviour of atoms: with a single X-ray flash, the group led by Daniel Rolles from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) in Hamburg (Germany) was able to kick a record number of 36 electrons at once out of a xenon atom. According to theoretical calculations, these are significantly more than should be possible at this energy of the X-ray radiation. The team present their unexpected observations in the ...

'Groundwater inundation' doubles previous predictions of flooding with future sea level rise

2012-11-12

Scientists from the University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM) published a study today in Nature Climate Change showing that besides marine inundation (flooding), low-lying coastal areas may also be vulnerable to "groundwater inundation," a factor largely unrecognized in earlier predictions on the effects of sea level rise (SLR). Previous research has predicted that by the end of the century, sea level may rise 1 meter. Kolja Rotzoll, Postdoctoral Researcher at the UHM Water Resources Research Center and Charles Fletcher, UHM Associate Dean, found that the flooded area in urban ...

Game changer for arthritis and anti-fibrosis drugs

2012-11-12

(SALT LAKE CITY)—In a discovery that can fundamentally change how drugs for arthritis, and potentially many other diseases, are made, University of Utah medical researchers have identified a way to treat inflammation while potentially minimizing a serious side effect of current medications: the increased risk for infection.

These findings provide a new roadmap for making powerful anti-inflammatory medicines that will be safer not only for arthritis patients but also for millions of others with inflammation-associated diseases, such as diabetes, traumatic brain injury, ...